Taxation in ancient Rome

[7] Jones argues that the stipendium likely developed into a provincial tax during the Punic Wars, citing an account from Livy which mentions that—during the campaign in Hispania—the Roman government had difficulty supplying or paying the soldiers, leading Scipio to compensate by exacting funds from the local tributaries.

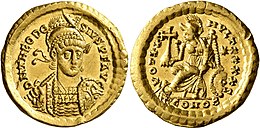

[20][21] Under Constantine, it had become difficult to pay taxes due to the continued debasement of the solidus, increasing the prevalence of payment in kind.

[24] Taxation in ancient Rome was decentralized, with the government preferring to leave the task of collecting taxes to local elected magistrates.

Difficulty identifying which members of the Egyptian populace were entitled to reduced taxation likely prompted a special census of these groups in the year 4 or 5 CE.

However, other manuscripts read "now many [pay] in money" instead of utilizing the word "alii" ("others"); historian Keith Hopkins favors the latter rendition, arguing the former derives from scribal error.

He notes that several cities in Sicily are exempt from taxation by the Roman government due to special treaties, these being Tauromenium, Centuripa, Segesta, Halaesus, Halyciae, Panormus, and Messina.

[23] Throughout Roman history, significant tax-debt may have accumulated as issues such as a poor harvest could prevent civilians from fully paying the tax burden.

Emperors, possibly as political gestures, sometimes forgave tax-debts: Marcus Aurelius in 178 CE forgave all tax arrears incurred over the past 45 years and Trajan burned fiscal records documenting unpaid taxes in a bonfire during his triumph commemorating his victory in the Dacian Wars, from which Trajan may have garnered the wealth to afford such a financial decision.

Although Augustus limited the power of the publicani significantly,[49] the Roman government assumed control of farming indirect taxes under the Flavian dynasty.

[50] According to the classicists Roscoe Pulliam and Keith Hopkins, the prevalence of self-assessment in the administration of Roman taxation may have created discrepancies between the quantity of funds levied by tax collectors and the finances that reached the Imperial treasury.

[51] This analysis is favored by Keith Hopkins, who estimated that Roman taxes likely constituted—on average—around 5-7% of the GDP of the empire, who also suggests that this may have originated from a lack of significant public services offered to governed regions.

Hopkins proposes that Roman involvement in provincial administration may have been restricted to the provision of military defense, limited law enforcement, and minor investments in local infrastructure.

[44] The Chronicon Paschale, a 7th-century Greek Christian chronicle, claims that this system was established in 49 BCE by Julius Caesar, although it is also possible it began in 48 BC.

[57] Throughout much of Roman history the tax burden was almost exclusively laid on the poorest people of the Empire while wealthier bureaucrats could avoid taxation.

[63] People who were unable to bear this burden would have agreed to become indebted to landlords in exchange for protection, effectively transforming them from free citizens into serfs.

Despite these reductions, the provinces of Rome struggled to pay their taxes, and the Roman government was unable to receive the funding it needed.

[69] Keith Hopkins suggested that taxation may have aided the growth of trade networks in the Roman Empire by helping to create an interconnected economy in which, through taxation, finances were collected from the provinces and spent in Italy or the frontier regions, and provinces were forced to increase production to recover their lost wealth.

[75] Another factor potentially impacting the economy in a similar manner was rent collection: the burden of rent—according to Hopkins—may also have also driven farmers to increase production to satisfy financial demands.

These rents would have been collected by wealthy landlords, who would have spent that money in cities and other areas distant from the original source of the funds.

[77] For instance, in Egypt farmers supplied portions of their crop yield in tax to the rest of the Roman Empire,[78] where it would then be sold to the populace in other regions and therefore converted into monetary wealth.

[80] Hopkins argues that the prevalence of taxes paid in-kind during the 3rd-century was both caused by and contributed to the economic depression of the that time period; the collapse of the fiscal system may have forced the government to adopt taxes paid in-kind, and—in doing so—they possibly crippled the aforementioned system of trade propagated by taxation.

These taxes were, according to Hopkins, often exclusively used to supply nearby military forces and therefore lacked the same implications for long-distance trade or ability to be reinvested into the economy.

Furthermore, Hopkins suggests that the increased bureaucracy of collecting and managing in-kind goods instead of currency liked served as an added drained on the economy.

[86][87] These tax reductions may have been partially motivated by political rather than economic concerns: One law dated to March 24, 390 offers tax-exemption for Campania under the condition that the province cease all complaints regarding abandoned land.

[87][88] According to the classicist Cam Grey, this legislation may have served to earn political favor with emphyteutic land-owners, who may have typically been wealthy and influential individuals that had been leased agrarian land for the purpose of cultivation.

[85] Authors from Late Antiquity sometimes claim that high levels of taxation motivated the depopulation of land across the Empire, with the 4th-century Greek rhetorician Libanius mentioning "Nowadays, though, you can go through miles of deserted farmland.

"[89] According to Jones, it is also possible that these grievances may have stemmed more from a general dislike of all changes to the existing tax structure as opposed to a genuinely severe financial burden.

[96] Whittaker suggests that the evidence for the pervasiveness of the supposed "agri deserti" ("deserted land") is scant and almost exclusively attested in sources of dubious reliability, casting doubt upon the notion that this issue was endemic to the Late Empire.

[98] The authors noted—among other sources—the presence of indicators of wealth throughout Late Antique tombs from the countryside, such a large number of lavish sarcophagi with expensive ornaments such as jewelry.

[99] Jones, however, maintains that over taxation of the peasantry likely contributed to rural depopulation in Late Empire, arguing that the poorest Romans were unable utilize political influence or wealth to circumvent or bribe tax collectors as wealthier individuals were, thereby rendering the poor subject to the excessive collection that eventually increased poverty.