Taxonomy (biology)

This is a field with a long history that in recent years has experienced a notable renaissance, principally with respect to theoretical content.

This analysis may be executed on the basis of any combination of the various available kinds of characters, such as morphological, anatomical, palynological, biochemical and genetic.

[17][18] Kinds of taxonomic characters include:[19] The term "alpha taxonomy" is primarily used to refer to the discipline of finding, describing, and naming taxa, particularly species.

[20] In earlier literature, the term had a different meaning, referring to morphological taxonomy, and the products of research through the end of the 19th century.

[22] ... there is an increasing desire amongst taxonomists to consider their problems from wider viewpoints, to investigate the possibilities of closer co-operation with their cytological, ecological and genetics colleagues and to acknowledge that some revision or expansion, perhaps of a drastic nature, of their aims and methods, may be desirable ... Turrill (1935) has suggested that while accepting the older invaluable taxonomy, based on structure, and conveniently designated "alpha", it is possible to glimpse a far-distant taxonomy built upon as wide a basis of morphological and physiological facts as possible, and one in which "place is found for all observational and experimental data relating, even if indirectly, to the constitution, subdivision, origin, and behaviour of species and other taxonomic groups".

[26][27][20] By extension, macrotaxonomy is the study of groups at the higher taxonomic ranks subgenus and above,[20] or simply in clades that include more than one taxon considered a species, expressed in terms of phylogenetic nomenclature.

The publication of Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species (1859) led to a new explanation for classifications, based on evolutionary relationships.

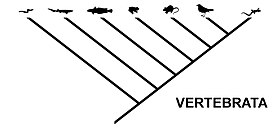

The advent of cladistic methodology in the 1970s led to classifications based on the sole criterion of monophyly, supported by the presence of synapomorphies.

Medicinal plant illustrations show up in Egyptian wall paintings from c. 1500 BC, indicating that the uses of different species were understood and that a basic taxonomy was in place.

[36] Taxonomy in the Middle Ages was largely based on the Aristotelian system,[38] with additions concerning the philosophical and existential order of creatures.

The Aristotelian system did not classify plants or fungi, due to the lack of microscopes at the time,[37] as his ideas were based on arranging the complete world in a single continuum, as per the scala naturae (the Natural Ladder).

[36] During the Renaissance and the Age of Enlightenment, categorizing organisms became more prevalent,[36] and taxonomic works became ambitious enough to replace the ancient texts.

This is sometimes credited to the development of sophisticated optical lenses, which allowed the morphology of organisms to be studied in much greater detail.

[47] His work from 1700, Institutiones Rei Herbariae, included more than 9,000 species in 698 genera, which directly influenced Linnaeus, as it was the text he used as a young student.

His works implemented a standardized binomial naming system for animal and plant species,[51] which proved to be an elegant solution to a chaotic and disorganized taxonomic literature.

He not only introduced the standard of class, order, genus, and species, but also made it possible to identify plants and animals from his book, by using the smaller parts of the flower (known as the Linnaean system).

[51] Plant and animal taxonomists regard Linnaeus' work as the "starting point" for valid names (at 1753 and 1758 respectively).

[37] The pattern of the "Natural System" did not entail a generating process, such as evolution, but may have implied it, inspiring early transmutationist thinkers.

[20] The idea was popularized in the Anglophone world by the speculative but widely read Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, published anonymously by Robert Chambers in 1844.

[54] With Darwin's theory, a general acceptance quickly appeared that a classification should reflect the Darwinian principle of common descent.

[56] Using the then newly discovered fossils of Archaeopteryx and Hesperornis, Thomas Henry Huxley pronounced that they had evolved from dinosaurs, a group formally named by Richard Owen in 1842.

[57][58] The resulting description, that of dinosaurs "giving rise to" or being "the ancestors of" birds, is the essential hallmark of evolutionary taxonomic thinking.

[65][28][9] Linnaean ranks are optional and have no formal standing under the PhyloCode, which is intended to coexist with the current, rank-based codes.

As advances in microscopy made the classification of microorganisms possible, the number of kingdoms increased, five- and six-kingdom systems being the most common.

[68] Thomas Cavalier-Smith, who published extensively on the classification of protists, in 2002[71] proposed that the Neomura, the clade that groups together the Archaea and Eucarya, would have evolved from Bacteria, more precisely from Actinomycetota.

[73] Partial classifications exist for many individual groups of organisms and are revised and replaced as new information becomes available; however, comprehensive, published treatments of most or all life are rarer; recent examples are that of Adl et al., 2012 and 2019,[81][82] which covers eukaryotes only with an emphasis on protists, and Ruggiero et al., 2015,[83] covering both eukaryotes and prokaryotes to the rank of Order, although both exclude fossil representatives.

[85] Because taxonomy aims to describe and organize life, the work conducted by taxonomists is essential for the study of biodiversity and the resulting field of conservation biology.

[89] In the fields of phycology, mycology, and botany, the naming of taxa is governed by the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (ICN).

[97] In phenetics, also known as taximetrics, or numerical taxonomy, organisms are classified based on overall similarity, regardless of their phylogeny or evolutionary relationships.