Teatro San Cassiano

Until then, public theatres (i.e., those operating on a commercial basis) had staged only recited theatrical performances (commedie)[2][3] while opera had remained a private spectacle, reserved for the aristocracy and the courts.

The project aims to establish the reconstructed Teatro San Cassiano as a centre for the research, exploration and staging of historically informed Baroque opera.

[6] In the cited letter, Tron writes of “expenditure of great significance for the recitation of comedies”, but he also hints at the popularity of his venture: — Ettore Tron to duke Alfonso II d’Este, 4 gennaio 1580 more veneto, transcribed I Teatri del Veneto cit., Tomo I, p. 126 Other than suggesting that the theatre was well received, this also confirms that theatre-boxes, which would later constitute one of the key architectural elements of the théâtre à l'italienne (an Italianate opera house), were already present in this first incarnation of the venue.

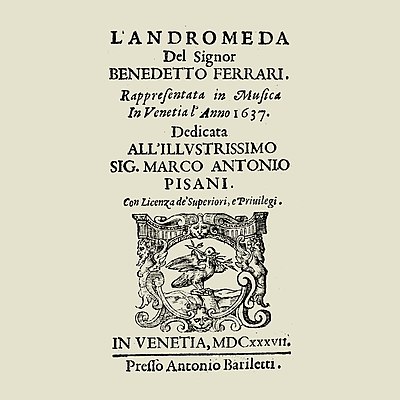

[16] In 1636, the Tron brothers (Ettore and Francesco, of the ‘branch’ of the San Benetto family) appear to have communicated to the authorities their intention to open a “Theatre for music”, thus clarifying from the outset its function as an opera house.

[20] The historical significance of this event is incalculable, as is the commercial practice established of purchasing of an entrance ticket by each spectator; a concept destined for global diffusion, but which occurs here as public opera for the first time.

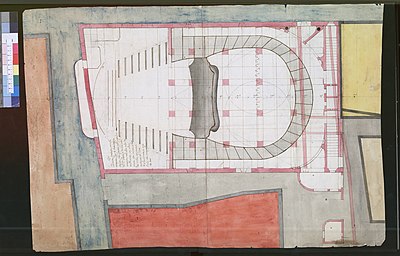

[21] Given the total absence of images relating to this phase of Teatro San Cassiano's history, a document stipulated by the Notary Alessandro Pariglia, dated 12 February 1657 more veneto, offers significant insight with regard to the internal structure of the auditorium.

[23] In his list of measurements relating to what Bognolo calls the “old Teatro San Cassiano” (dating back to 1696 or further to 1670), the architect specifies “total boxes: number 31 per tier”, exactly as cited by Chassebras.

Indeed, it should be pointed out that with regard to the first 25 years of Venetian opera production, by comparison to the approximately one hundred surviving printed librettos, only about thirty scores, all handwritten, remain extant today, of which two thirds are Cavalli’s”.

Indeed, it was Gianettini's opera L’ingresso alla gioventù di Claudio Nerone (Modena, 1692), which became the first Teatro San Cassiano co-production of the reconstruction project when it received its modern-day premiere in September 2018, in the castle theatre of Český Krumlov, conductor Ondřej Macek.

As for the ‘new’ Teatro San Cassiano, inaugurated with La morte di Dimone (1763), music by Antonio Tozzi and libretto by Johann Joseph Felix von Kurz and Giovanni Bertati, the main difference was with regard the deeper stage, achieved by the extending the length of the theatre by demolishing two small houses which, with reference to the ‘old’ Teatro San Cassiano, stood against its end wall located a few metres from the outer curve of the boxes.

In 1776, if Giacomo Casanova is to be taken in good faith, the Teatro San Cassiano had become a place where “women of the underworld and prostitute young men commit in the boxes of the fifth tier those crimes that the Government, in tolerating them, wants at least not to be exposed to the sight of others”, a description that has led to suppose an early state of degradation and decay.

[30] The last known season was that of 1798, during which two operas were performed: La sposa di stravagante temperamento (as we read in the libretto, “the music is by Mr Pietro Guglielmi, Neapolitan chapel master.

The scenario will be entirely invented and directed by Mr Luigi Facchinelli, from Verona”)[31] and Gli umori contrari (music by Sebastiano Nasolini, libretto by Giovanni Bertati).