Tehuelche people

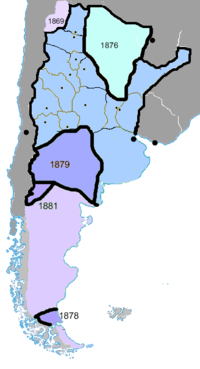

Once a nomadic people, the lands of the Tehuelche were colonized in the 19th century by Argentina and Chile, gradually disrupting their traditional economies.

[3] According to the historian Antonio Pigafetta from Ferdinand Magellan's expedition in 1520, he referred to the indigenous people he came across in the San Julian Bay as the "Patagoni".

In other cases, the seasonal migrations that they practiced which involved traveling long distances made Europeans that observed them overestimate the number of people from a group or the distribution range of a language.

All these, except those of the River, are called by the Moluches, Vucha-Huilliches.In 1936 Milcíades Vignati published Las culturas indígenas de la Pampa y Las culturas indígenas de la Patagonia (The Indigenous Cultures of the Pampas and the Indigenous Cultures of Patagonia) in which he proposed that between the 16th and 19th centuries the "Gününa-küne" or "Tuelches" lived from the southern half of the province of Rio Negro to the boundary between the present Chubut and Santa Cruz provinces.

An Ethnographic study of Patagonians), the military doctor Federico A. Escalada classified the Tehuelche people from historic periods, on the basis of the Estudio de la realidad humana y de la bibliografía (Study of Human Reality and Bibliography), into five simple categories, each with their own language derived from a mother language called "Ken".

[9] The names used by Escalada, which he obtained from Mapuche-speaking informants, were: Argentine historian and paleontologist Rodolfo Casamiquela reviewed Escalada's classifications in his books Rectificaciones y ratificaciones hacia una interpretación definitiva del panorama etnológico de la Patagonia y área septentrional adyacente (Rectifications and ratifications towards a definitive interpretation of the ethnological panorama of Patagonia and the adjacent Northern area) (1965); Un nuevo panorama etnológico del area pan-pampeana y patagónica adyacente (A new ethnological panorama of the Pan-Pampas and adjacent Patagonian area) (1969); and Bosquejo de una etnología de la provincia de Río Negro (Outline of an ethnology of the Río Negro province) (1985), reaffirming the existence of a Tehuelche complex.

There is a group of people who try to recover the language through a program called "Kkomshkn e wine awkkoi 'a'ien" ("I am not ashamed of speaking Tehuelche").

In 1913, Lehmann Nitsche used the data collected by Hunziker and Claraz to create a comparative vocabulary of Tehuelche languages: El grupo lingüístico tschon de los territorios magallánicos (The Chonan Linguistic Groups of the Magellanic Territories).

In 1991, José Pedro Viegas Barros outlined a morphosyntactic projection in Clarificación lingüística de las relaciones interculturales e interétnicas en la región pampeano-patagónica (Linguistic Clarification of Intercultural and Inter-ethnic Relations in the Pampas-Patagonian Region), and in 2005 he developed a phonological description in Voces en el viento[20][22] (Voices in the Wind).

The boundaries of these territories were defined through ancestry by markers with unknown significance: a hill, a trough, a hollow, or important tree.

However, like all the Pampas and Patagonian peoples, they had a corpus of beliefs based on their own myths and rituals, which were narrated and updated by the shamans who also practiced medicine with the help of the spirits invoked in themselves.

One of the cosmological versions of the creation myth is one in which the deity, known as Kóoch, brought order to the world's chaos, creating distinct elements.

[citation needed] Also, within Tehuelche myth, through the god Temauckel, Erral created humans and taught them how to use bows and arrows.

[24] The ancestors of the Tehuelche are probably responsible for the creation of the rock art of Cueva de las Manos, created from about 13,000 to 9,000 years ago up until around 700 A.D.[25][26][27] Six thousand years ago the Toldense industry emerged, consisting primarily of goods such as two-sided sub-triangular projectile points, lateral and terminal scrapers, bifacial knives and tools made from bone.

Later, between 7000 and 4000 B.C., the Casapedrense industry appeared, characterized by a greater proportion of stone tools made in sheets, which was most likely a demonstration of a specialization in guanaco hunting,[28] which is also present in the subsequent cultural developments of the Tehuelche people.

From this time and until the European arrival (early 16th century) the Tehuelche people were hunter-gatherers who utilized seasonal mobility, moving towards guanaco herds.

), and during the summer they moved up to the central plateaus of Patagonia or to the Andes mountains where they had, among other sacred sites, Mount Fitz Roy.

On 31 March 1520 the Spanish expedition, under the command of Fernando de Magallanes, landed in San Julián Bay to spend the winter there.

[24] By 1828, the Pincheira Royalist army attacked the Tehuelche group in the Bahía Blanca and Carmen de Patagones area.

The Tehuelche people had to live with Welsh immigrants who, since the second half of the 19th century, began to settle in Chubut: the relations were generally harmonious between the two groups.

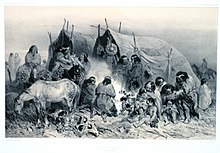

Little information is known about Tehuelche culture before the use of the horse, although their socioeconomic organization resembled that of the Ona people from Tierra del Fuego.

Like the indigenous groups in the North American Great Plains, the Tehuelche also worked the thicket steppes of Patagonia, living mainly off of guanaco and rhea meat (ñandú or choique), followed by South Andean deer, deer, Patagonian mara and even puma and jaguar meat, in addition to certain plants (although late, they learned how to cultivate the land).

Their groups used to consist of between 50 and 100 members.The adoption of the horse meant an extensive social change in Tehuelche culture: the new mobility altered their ancestral territories and greatly affected their movement patterns.

and apples with the Gennakenk people of Neuquén, the upper valley of Río Negro and the so-called 'country of Strawberries', or Chulilaw (the region approximately bounded to the north by Lake Nahuel Huapi, to the east by the low mountains and morraines called Patagónides, to the west by the high summits of the Andes and to the south by Lake Buenos Aires/General Carrera).

[36][contradictory] As early as the second half of the 19th century, Tehuelche groups were abducted and displayed against their will in countries such as Belgium, Switzerland, (Germany), France and England.

Reports of these shocking facts form part of Christian Báez and Peter Mason's book Zoológicos humanos[37] (Human Zoos).

[38] By decree of President José Evaristo Uriburu on 11 January 1898, the Camusu Aike reservation was created for the "gathering of Tehuelche tribes".

The census recorded that in Santa Cruz Province:[43] There were also inter-mixed marriages in Tres Lagos, Puerto San Julián, Gobernador Gregores and Río Gallegos.

El Chalía, the Manuel Quilchamal community, in the Río Senguer Department, located 60 km from the Doctor Ricardo Rojas village.

In 1905 they suffered a smallpox epidemic that killed Chief Mulato and other members of his settled tribe in the río Zurdo valley, near Punta Arenas.