Telegraph code

The Chappe system mostly transmitted messages using a code book with a large number of set words and phrases.

However, the proposal in 1793 was for ten code points representing the numerals 0–9, and Bouchet says this system was still in use as late as 1800 (Holzmann & Pehrson put the change at 1795).

In 1837 a horizontal only coding system was introduced by Gabriel Flocon which did not require the heavy regulator to be moved.

The symbols without "A" were a large set of numerals, letters, common syllables and words to aid code compaction.

Usually, messages were expected to be passed all the way down the line, but there were circumstances when individual stations needed to communicate directly, usually for managerial purposes.

The much larger mechanical apparatus of the semaphore telegraph towers was needed so that a greater distance between links could be achieved.

C&W5 had the major advantage that the code did not need to be learned by the operator; the letters could be read directly off the display board.

In the US, American Morse code was used, whose elements consisted of dots and dashes distinguished from each other by the length of the pulse of current on the telegraph line.

[5] In Germany in 1848, Friedrich Clemens Gerke developed a heavily modified version of American Morse for use on German railways.

In 1851, the Union decided to adopt a common code across all its countries so that messages could be sent between them without the need for operators to recode them at borders.

This was a similar advantage to the Morse telegraph in which the operators could hear the message from the clicking of the relay armature.

This resulted in international operators needing to be fluent in both versions of Morse and to recode both incoming and outgoing messages.

The second reason is that American Morse is more prone to intersymbol interference (ISI) because of the larger density of closely spaced dots.

This problem was particularly severe on submarine telegraph cables, making American Morse less suitable for international communications.

The Chinese telegraph code uses a codebook of around 9,800 characters (7,000 when originally launched in 1871) which are each assigned a four-digit number.

[10] Early printing telegraphs continued to use Morse code, but the operator no longer sent the dots and dashes directly with a single key.

Murray completely rearranged the character encoding to minimise wear on the machine since operator fatigue was no longer an issue.

The five bits of the Baudot code are insufficient to represent all the letters, numerals, and punctuation required in a text message.

Its intended purpose was to remove erroneous characters from the tape, but Murray also used multiple DELs to mark the boundary between messages.

Having all the holes punched out made a perforation which was easy to tear into separate messages at the receiving end.

Teleprinters were quickly adopted by news organizations, and "wire services" supplying stories to multiple newspapers developed, but an additional application soon arose: sending finished copy from an urban newsroom to a remote printing plant.

The limited character repertoire of the 5-level codes meant that someone had to manually retype the telegram in mixed case, a laborious and error-prone operation.

To compete, the Mergenthaler Linotype Company developed a TeleTypeSetter (TTS) system which functioned similarly, but using a narrower 6-level code (the name "bit" would not be coined until 1948) which was more economical to transmit.

TTS retained shift and unshift control characters, but they operated much like a modern keyboard: the unshift state provided lower-case letters, digits, and common punctuation, while the shift state provided upper-case letters and special symbols.

TTS also included Linotype-specific features such as ligatures and a second "upper rail" shift function usually used for italic type.

Adding the 8 fixed-width characters which are duplicated in the two shift states, this matches the 90-matrix capacity of a standard Linotype machine.

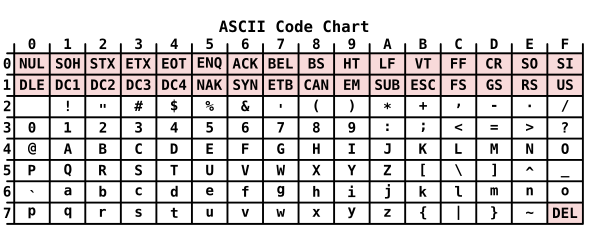

The first computers used existing 5-bit ITA-2 keyboards and printers due to their easy availability, but the limited character repertoire quickly became a pain point.

ISO 8859 character encodings were developed for non-Latin scripts such as Cyrillic, Hebrew, Arabic, and Greek.

20-bit Unicode provided support for extinct languages such as Old Italic script and many rarely used Chinese characters.

[32] When used with a printing telegraph or siphon recorder, the "dashes" of dot-dash codes are often made the same length as the "dot".