Telegrapher's equations

The equations are important because they allow transmission lines to be analyzed using circuit theory.

[1] The equations and their solutions are applicable from 0 Hz (i.e. direct current) to frequencies at which the transmission line structure can support higher order non-TEM modes.

The equations come from Oliver Heaviside who developed the transmission line model starting with an August 1876 paper, On the Extra Current.

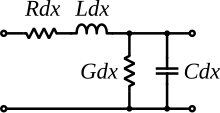

In a more practical approach, one assumes that the conductors are composed of an infinite series of two-port elementary components, each representing an infinitesimally short segment of the transmission line: The model consists of an infinite series of the infinitesimal elements shown in the figure, and that the values of the components are specified per unit length so the picture of the component can be misleading.

to emphasize that the values are derivatives with respect to length, and that the units of measure combine correctly.

The role of the different components can be visualized based on the animation at right.

All four parameters L, C, R, and G depend on the material used to build the cable or feedline.

The figure at right shows a lossless transmission line, where both R and G are zero, which is the simplest and by far most common form of the telegrapher's equations used, but slightly unrealistic (especially regarding R).

In practice, before that point is reached, a transmission line with a better dielectric is used.

In long distance rigid coaxial cable, to get very low dielectric losses, the solid dielectric may be replaced by air with plastic spacers at intervals to keep the center conductor on axis.

They can be combined to get two partial differential equations, each with only one dependent variable, either

The telegrapher's equations in the frequency domain are developed in similar forms in the following references: Kraus,[7] Hayt,[1] Marshall,[8]: 59–378 Sadiku,[9]: 497–505 Harrington,[10] Karakash,[11] Metzger.

[1]: 385 Each of the preceding partial differential equations have two homogeneous solutions in an infinite transmission line.

The negative sign in the previous equation indicates that the current in the reverse wave is traveling in the opposite direction.

, wire resistance and insulation conductance can be neglected, and the transmission line is considered as an ideal lossless structure.

The telegrapher's equations then describe the relationship between the voltage V and the current I along the transmission line, each of which is a function of position x and time t:

The first equation shows that the induced voltage is related to the time rate-of-change of the current through the cable inductance, while the second shows, similarly, that the current drawn by the cable capacitance is related to the time rate-of-change of the voltage.

is the propagation speed of waves traveling through the transmission line.

In the case of sinusoidal steady-state (i.e., when a pure sinusoidal voltage is applied and transients have ceased), the voltage and current take the form of single-tone sine waves:[13]

are arbitrary constants of integration, which are determined by the two boundary conditions (one for each end of the transmission line).

represents the amplitude profile of a wave traveling from left to right – in a positive

are too substantial to ignore, the differential equations describing the elementary segment of line are

These extra terms cause the signal to decay and spread out with time and distance.

[14] The solutions of the telegrapher's equations can be inserted directly into a circuit as components.

The circuit in the figure implements the solutions of the telegrapher's equations.

The line parameters Rω, Lω, Gω, and Cω are subscripted by ω to emphasize that they could be functions of frequency.

The voltage and current relations are symmetrical: Both of the equations shown above, when solved for

Every two-wire or balanced transmission line has an implicit (or in some cases explicit) third wire which is called the shield, sheath, common, earth, or ground.

The circuit shown in the bottom diagram only can model the differential mode.

This circuit is a useful equivalent for an unbalanced transmission line like a coaxial cable.