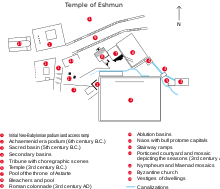

Temple of Eshmun

Although originally constructed by Sidonian king Eshmunazar II in the Achaemenid era (c. 529–333 BC) to celebrate the city's recovered wealth and stature, the temple complex was greatly expanded by Bodashtart, Yatonmilk and later monarchs.

Because the continued expansion spanned many centuries of alternating independence and foreign hegemony, the sanctuary features a wealth of different architectural and decorative styles and influences.

The sanctuary consists of an esplanade and a grand court limited by a huge limestone terrace wall that supports a monumental podium which was once topped by Eshmun's Greco-Persian style marble temple.

The sanctuary features a series of ritual ablution basins fed by canals channeling water from the Asclepius river (modern Awali) and from the sacred "YDLL" spring;[nb 1] these installations were used for therapeutic and purificatory purposes that characterize the cult of Eshmun.

The Eshmun Temple was improved during the early Roman Empire with a colonnade street, but declined after earthquakes and fell into oblivion as Christianity replaced polytheism and its large limestone blocks were used to build later structures.

[4] Eshmun was identified with Asclepius as a result of the Hellenic influence over Phoenicia; the earliest evidence of this equation is given by coins from Amrit and Acre from the third century BC.

These payments stimulated Sidon's search for new means of provisioning and furthered Phoenician emigration and expansion, which peaked in the 8th century BC.

Archaeological evidence suggest that, at the time of the advent of the Eshmunazar dynasty, there already was a cultic space on the site of the temple, but there were no monumental constructions yet.

[13] In the following years, Xerxes I awarded king Eshmunazar II with the Sharon plain[nb 4] for employing Sidon's fleet in his service during the Greco-Persian Wars.

The practice of intentional inscription concealment can be traced back to Mesopotamian roots, and it has parallels in the royal buildings of the Achaemenids in Persia and Elam.

Furthermore, within the original Phoenician temple site the Romans added the processional stairway, the basins for ablutions and a nymphaeum with pictorial mosaics, that are still largely intact.

For many years after the disappearance of the cult of Eshmun, the sanctuary site was used as a quarry:[22] Emir Fakhr-al-Din II used its massive blocks to build a bridge over the Awali river in the 17th century.

[25] The site later fell into oblivion until the 19th century[22] Between 1737 and 1742, Richard Pococke, an English anthropologist, toured the Middle East and wrote of what he thought were ruins of defensive walls built with 3.7-metre (12 ft) stone blocks near the Awali river.

When the French orientalist Ernest Renan visited the area in 1860, he noticed that the Awali bridge abutments were built of finely rusticated blocks that originated from an earlier structure.

He also noted in his report, Mission de Phénicie, that a local treasure hunter told him of a large edifice near the Awali bridge.

Today the Eshmun sanctuary can be visited all year round and free of charge, it is accessible from an exit ramp off the main Southern Lebanon highway near Sidon's northern entrance.

[4][37][38][39] Strabo[nb 6] and other Sidonian sources describe the sanctuary and its surrounding "sacred forests" of Asclepius, the Hellenized name of Eshmun, in written texts.

[4][40] Built under Babylonian rule (605–539 BC),[4] the oldest monument at the site was a pyramidal building resembling a ziggurat that included an access ramp to a water cistern.

[28][44] The chapel was adorned with a paved pool and a large stone "Throne of Astarte" carved of a single block of granite in the Egyptian style;[4][21][28] it is flanked by two sphinx figures and surrounded by two lion sculptures.

The throne, attributed to the Sidonian goddess Astarte, rests against the chapel wall, which is embellished by relief sculptures of hunting scenes.

[44] The west base contains another 4th-century BC chapel – centered on a bull protome topped capital – that remains preserved at the National Museum of Beirut.

The lower register honors Dionysus, who leads his thiasos (his ecstatic retinue) in a dance to the music of pipe and cithara players.

Its 22-metre (72 ft) façade is built with large limestone blocks and displays a two-register relief decoration illustrating a drunken revelry in honor of Dionysus, the Greek god of wine.

[52][53] There is evidence that from the 3rd century BC onwards there have been attempts to Hellenize the cult of Eshmun and to associate him with his Greek counterpart Asclepius, but the sanctuary retained its curative function.

[54] Apart from the large decorative elements, carved friezes and mosaics which were left in situ, many artifacts were recovered and moved from the Eshmun Temple to the National Museum of Beirut, the Louvre or are in possession of the Lebanese directorate general of antiquities.

[7][28][53] These votive sculptures appear to have been purposely broken after dedication to Eshmun and then ceremoniously cast into the sacred canal, probably simulating the sacrifice of the sick child.

Rolf Stucky, ex-director of the Institute of Classical Archaeology of Basel affirmed during a conference in Beirut in December 2009 the successful identification and return of eight sculptures to the Lebanese national museum.