Temporary Slavery Commission

The TSC conducted a global investigation concerning slavery, slave trade and forced labor, and recommended solutions to address the issues.

[1] The TSC was preceded by the Brussels Anti-Slavery Conference 1889–90, which had addressed slavery in a semi-global level via representatives of the colonial powers.

The League of Nations conducted an informal investigation about the existence of slavery and slave trade in 1922–1923, gathering information from both governments as well as NGO's such as the Anti-Slavery Society and the Bureau international pour la défense des indigènes (International Bureau for the Defense of the Native Races, BIDI).

The colonial powers were slow to send enough information to form a report, which contributed to the decision to found a formal commission.

[3] The result of the report demonstrated the situation with chattel slavery in the Arabian Peninsula, Sudan and Tanganyika, as well as the illegal trafficking and force labor in the French colonies, South Africa, Portuguese Mozambique and Latin America.

When all governments answered with the reply that slavery did not exist within their territories, or had already been abolished, the League saw the need to establish a committee to conduct a formal investigation.

[5] The TSC was to conduct a formal international investigation of all slavery and slave trade globally, and act for its total abolition.

[6] Every state previously known to have had slavery was encouraged to answer how they had combated it, which effects it had resulted in, and if they had considered further action, and to name individuals or organizations that could provide further information.

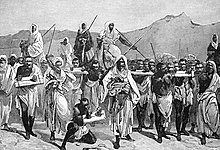

[11] The report on Sudan to the Temporary Slavery Commission (TSC) described the enslavement of Nilotic Non-Muslims of the South West by the Muslim Arabs in the North, where most agriculture was still managed by slave labor in 1923.

[12] The British colonial authorities actively fought the slave trade in Sudan but avoided addressing slavery itself for fear of causing unrest.

When this fact was raised in the House of Lords, however, the colonial administration was ordered to publish and enforce the provisions against slavery in Sudan.

[19] The most prominent slave trader was Khojali al-Hassan, "Watawit" shaykh of Bela Shangul in Wallagi, and his principal wife Sitt Amna, who had been acknowledged by the British as the head of an administrative unit in Sudan in 1905.

Khojali al-Hassan collected slaves – normally adolescent girls and boys or children – by kidnapping, debt servitude or as tribute from his feudal subjects, and would send them across the border to his wife, who sold them to buyers in Sudan.

[20] British Consul Hodson in Ethiopia reported that the 1925 edict had no practical effect on slavery and slave trade conducted across the Sudanese-Ethiopian border to Tishana: the Ethiopians demanded taxes and took children of people who could not pay and enslaved them; slave raids were still conducted against villages at nighttime by bandits burning huts, killing old and enslaving young.