Tensor algebra

The tensor algebra also has two coalgebra structures; one simple one, which does not make it a bi-algebra, but does lead to the concept of a cofree coalgebra, and a more complicated one, which yields a bialgebra, and can be extended by giving an antipode to create a Hopf algebra structure.

Note: In this article, all algebras are assumed to be unital and associative.

We then construct T(V) as the direct sum of TkV for k = 0,1,2,… The multiplication in T(V) is determined by the canonical isomorphism given by the tensor product, which is then extended by linearity to all of T(V).

for negative integers k. The construction generalizes in a straightforward manner to the tensor algebra of any module M over a commutative ring.

If R is a non-commutative ring, one can still perform the construction for any R-R bimodule M. (It does not work for ordinary R-modules because the iterated tensor products cannot be formed.)

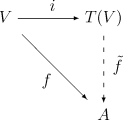

This means that any linear map between K-vector spaces U and W extends uniquely to a K-algebra homomorphism from T(U) to T(W).

If we take basis vectors for V, those become non-commuting variables (or indeterminates) in T(V), subject to no constraints beyond associativity, the distributive law and K-linearity.

The development provided below can be equally well applied to the exterior algebra, using the wedge symbol

; a sign must also be kept track of, when permuting elements of the exterior algebra.

obey the required consistency conditions for the definition of a bialgebra and Hopf algebra; this can be explicitly checked in the manner below.

Whenever one has a product obeying these consistency conditions, the construction goes through; insofar as such a product gave rise to a quotient space, the quotient space inherits the Hopf algebra structure.

But there is also a functor Λ taking vector spaces to the category of exterior algebras, and a functor Sym taking vector spaces to symmetric algebras.

The coalgebra is obtained by defining a coproduct or diagonal operator Here,

symbol is used to denote the "external" tensor product, needed for the definition of a coalgebra.

by a plain dot, or even drop it altogether, with the understanding that it is implied from context.

This is not done below, and the two symbols are used independently and explicitly, so as to show the proper location of each.

It is straightforward to verify that this definition satisfies the axioms of a coalgebra: that is, that where

That is, Continuing in this fashion, one can obtain an explicit expression for the coproduct acting on a homogenous element of order m: where the

The shuffle follows directly from the first axiom of a co-algebra: the relative order of the elements

It is a straightforward matter to verify that this counit satisfies the needed axiom for the coalgebra: Working this explicitly, one has where, for the last step, one has made use of the isomorphism

A bialgebra defines both multiplication, and comultiplication, and requires them to be compatible.

Multiplication is given by an operator which, in this case, was already given as the "internal" tensor product.

is "trivial": it is just part of the standard definition of the tensor product of vector spaces.

More verbosely, the axioms for an associative algebra require the two homomorphisms (or commuting diagrams): on

The unit and counit, and multiplication and comultiplication, all have to satisfy compatibility conditions.

It is straightforward to see that Similarly, the unit is compatible with comultiplication: The above requires the use of the isomorphism

The Hopf algebra adds an antipode to the bialgebra axioms.

by This extends homomorphically to Compatibility of the antipode with multiplication and comultiplication requires that This is straightforward to verify componentwise on

One may proceed in a similar manner, by homomorphism, verifying that the antipode inserts the appropriate cancellative signs in the shuffle, starting with the compatibility condition on

One may define a different coproduct on the tensor algebra, simpler than the one given above.