Covariant derivative

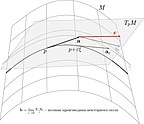

In the special case of a manifold isometrically embedded into a higher-dimensional Euclidean space, the covariant derivative can be viewed as the orthogonal projection of the Euclidean directional derivative onto the manifold's tangent space.

Historically, at the turn of the 20th century, the covariant derivative was introduced by Gregorio Ricci-Curbastro and Tullio Levi-Civita in the theory of Riemannian and pseudo-Riemannian geometry.

[2] Ricci and Levi-Civita (following ideas of Elwin Bruno Christoffel) observed that the Christoffel symbols used to define the curvature could also provide a notion of differentiation which generalized the classical directional derivative of vector fields on a manifold.

[3][4] This new derivative – the Levi-Civita connection – was covariant in the sense that it satisfied Riemann's requirement that objects in geometry should be independent of their description in a particular coordinate system.

It was soon noted by other mathematicians, prominent among these being Hermann Weyl, Jan Arnoldus Schouten, and Élie Cartan,[5] that a covariant derivative could be defined abstractly without the presence of a metric.

The crucial feature was not a particular dependence on the metric, but that the Christoffel symbols satisfied a certain precise second-order transformation law.

This transformation law could serve as a starting point for defining the derivative in a covariant manner.

Thus the theory of covariant differentiation forked off from the strictly Riemannian context to include a wider range of possible geometries.

In the 1940s, practitioners of differential geometry began introducing other notions of covariant differentiation in general vector bundles which were, in contrast to the classical bundles of interest to geometers, not part of the tensor analysis of the manifold.

By and large, these generalized covariant derivatives had to be specified ad hoc by some version of the connection concept.

In particular, Koszul connections eliminated the need for awkward manipulations of Christoffel symbols (and other analogous non-tensorial objects) in differential geometry.

Thus they quickly supplanted the classical notion of covariant derivative in many post-1950 treatments of the subject.

A vector at a particular time t[8] (for instance, a constant acceleration of the particle) is expressed in terms of

The covariant derivative of the basis vectors (the Christoffel symbols) serve to express this change.

In a curved space, such as the surface of the Earth (regarded as a sphere), the translation of tangent vectors between different points is not well defined, and its analog, parallel transport, depends on the path along which the vector is translated.

The same effect occurs if we drag the vector along an infinitesimally small closed surface subsequently along two directions and then back.

This infinitesimal change of the vector is a measure of the curvature, and can be defined in terms of the covariant derivative.Suppose an open subset

(Since the manifold metric is always assumed to be regular,[clarification needed] the compatibility condition implies linear independence of the partial derivative tangent vectors.)

The last term is not tangential to M, but can be expressed as a linear combination of the tangent space base vectors using the Christoffel symbols as linear factors plus a vector orthogonal to the tangent space:

From here it may be computationally convenient to obtain a relation between the Christoffel symbols for the Levi-Civita connection and the metric.

For a very simple example that captures the essence of the description above, draw a circle on a flat sheet of paper.

Now the (Euclidean) derivative of your velocity has a component that sometimes points inward toward the axis of the cylinder depending on whether you're near a solstice or an equinox.

Conversely, at a point (1/4 of a circle later) when the velocity is along the cylinder's bend, the inward acceleration is maximum.)

is defined in a way to make the resulting operation compatible with tensor contraction and the product rule.

is defined as the unique one-form at p such that the following identity is satisfied for all vector fields u in a neighborhood of p

In the theory of Riemannian and pseudo-Riemannian manifolds, the components of the Levi-Civita connection with respect to a system of local coordinates are called Christoffel symbols.

The first term in this formula is responsible for "twisting" the coordinate system with respect to the covariant derivative and the second for changes of components of the vector field u.

Incidentally, this particular expression is equal to zero, because the covariant derivative of a function solely of the metric is always zero.

In textbooks on physics, the covariant derivative is sometimes simply stated in terms of its components in this equation.

A covariant derivative introduces an extra geometric structure on a manifold that allows vectors in neighboring tangent spaces to be compared: there is no canonical way to compare vectors from different tangent spaces because there is no canonical coordinate system.