Terahertz time-domain spectroscopy

Components of a typical THz-TDS instrument, as illustrated in the figure, include an infrared laser, optical beamsplitters, beam steering mirrors, delay stages, a terahertz generator, terahertz beam focusing and collimating optics like parabolic mirrors, and detector.

Constructing a THz-TDS experiment using low temperature grown GaAs (LT-GaAs) based antennas requires a laser whose photon energy exceeds the band gap of the material.

Ti:sapphire lasers tuned to around 800 nm, matching the energy gap in LT-GaAs, are ideal as they can generate optical pulses as short as 10 fs.

Alternatively, nitrogen, as a diatomic molecule, has no electric dipole moment, and does not (for the purposes of typical THz-TDS) absorb THz radiation.

Thus, a purge box may be filled with nitrogen gas so no unintended discrete absorptions in the THz frequency range occur.

Radiation from an effective point source, such as from a low-temperature gallium arsenide (LT-GaAs) antenna (active region ~5 μm) incident on an off-axis parabolic mirror becomes collimated, while collimated radiation incident on a parabolic mirror is focused to a point (see diagram).

Terahertz radiation can thus be manipulated spatially using optical components such as metal-coated mirrors as well as lenses made from materials that are transparent at THz wavelengths.

Many materials are transparent at terahertz wavelengths, and this radiation is safe for biological tissue being non-ionizing (as opposed to X-rays).

Demonstrated examples include several different types of explosives, dynamic fingerprinting of DNA and protein molecules using polarization varying anisotropic terahertz microspectroscopy,[2] polymorphic forms of many compounds used as active pharmaceutical ingredients (API) in commercial medications as well as several illegal narcotic substances.

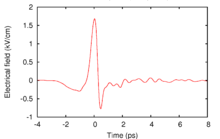

Though not strictly a spectroscopic technique, the ultrashort width of THz radiation pulses allows for measurements (e.g., thickness, density, defect location) on difficult-to-probe materials like foam.

Most carriers are generated near the surface of the material (typically within 1 micrometre) because pulses are absorbed exponentially with respect to depth.

Firstly, it generates a band bending that has the effect of accelerating carriers of different signs in opposite directions (normal to the surface), creating a dipole.

When generating THz radiation via a photoconductive emitter, an ultrafast pulse (typically 100 femtoseconds or shorter) creates charge carriers (electron-hole pairs) in a semiconductor material.

In a commonly used scheme, the electrodes are formed into the shape of a simple dipole antenna with a gap of a few micrometers and have a bias voltage up to 40 V between them.

For use with amplified Ti:sapphire lasers with pulse energies of about 1 mJ, the electrode gap can be increased to several centimeters with a bias voltage of up to 200 kV.

More recent advances towards cost-efficient and compact THz-TDS systems are based on mode-locked fiber laser sources emitting at a center wavelength of 1550 nm.

[5] The peak power during pulses can be many orders of magnitude higher due to the low duty cycle of mostly >1%, which is dependent on the repetition rate of the laser source.

However due to the coherent sampling techniques described, high S/N values (>70 dB) are routinely observed with 1 minute averaging times.

As with the generation, the bandwidth of the detection is dependent on the laser pulse duration, material properties, and crystal thickness.

In contrast, measuring only the power at each frequency is essentially a photon counting technique; information regarding the phase of the light is not obtained.

There is a difficulty in applying the Kramers-Kronig relations as written, because information about the sample (reflected power, for example) must be obtained at all frequencies.