Texas in the American Civil War

Texas declared its secession from the Union on February 1, 1861, and joined the Confederate States on March 2, 1861, after it had replaced its governor, Sam Houston, who had refused to take an oath of allegiance to the Confederacy.

Some Texan military units fought in the Civil War east of the Mississippi River, but Texas was more useful for supplying soldiers and horses for the Confederate Army.

Texas' supply role lasted until mid-1863, when Union gunboats started to control the Mississippi River, which prevented large transfers of men, horses, or cattle.

[4] The document specifies several reasons for secession, including its solidarity with its "sister slave-holding States," the U.S. government's inability to prevent Indian attacks, slave-stealing raids, and other border-crossing acts of banditry.

Unlike the other "cotton states"' chief executives, who took the initiative in secessionist efforts, Houston refused to call the Texas Legislature into special session to consider the question, relenting only when it became apparent citizens were prepared to act without him.

In early December 1860, before South Carolina even seceded, a group of State officials published via newspaper a call for a statewide election of convention delegates on January 8, 1861.

[2] Though he expressed reservations about the election of Abraham Lincoln, he urged the State of Texas to reject secession, citing the horrors of war and a probable defeat of the South.

The ordinance was read on the floor the next day, citing the failures of the federal government to protect the lives and property of Texas citizens and accusing the Northern states of using the same as a weapon to "strike down the interests and prosperity"[3] of the Southern people.

[3] In the interests of historical significance and posterity, the ordinance was written to take effect on March 2, the date of Texas Declaration of Independence (and, coincidentally, Houston's birthday).

On February 1, members of the Legislature, and a huge crowd of private citizens, packed the House galleries and balcony to watch the final vote on the question of secession.

Appreciating his style, the crowd afforded him a grudging round of applause (like many Texans who initially opposed secession, Throckmorton accepted the result and served his state, rising to the rank of brigadier-general in the Confederate army).

The last order of business was to appoint a delegation to represent Texas in Montgomery, Alabama, where their counterparts from the other six seceding states were meeting to form a new Confederacy.

Along with land baron Samuel A. Maverick and Thomas J. Devine, Dr. Philip N. Luckett met with U.S. Army General David E. Twiggs on February 8, 1861, to arrange the surrender of the federal property in San Antonio, including the military stores being housed in the old Alamo mission.

As a result of the negotiations, Twiggs (and Billy Jim Jack) delivered his entire command and its associated Army property (10,000 rifled muskets) to the Confederacy, an act that brought cries of treason from Unionists throughout the state.

Shortly afterwards, he accepted a commission as general in the Confederate Army but was so upset by being branded a traitor that he wrote a letter to Buchanan stating the intention to call upon him for a "personal interview" (then a common euphemism to fight a duel).

[14] Future Confederate general Robert E. Lee, then still a colonel in the U.S. Army, was in San Antonio at the time and when he heard the news of the surrender to Texas authorities, responded, "Has it come so soon as this?

The referendum on the issue indicated that some 25% of the (predominantly white) males eligible to vote favored remaining in the Union at the time the question was originally considered.

Some of the leaders initially opposed to secession accepted the Confederate cause once the matter was decided, some withdrew from public life, others left the state, and a few even joined the Union army.

[19] In August 1862, Confederate soldiers under Lt. Colin D. McRae tracked down a band of German Texans headed out of state and attacked their camp in a bend of the Nueces River.

[25][26]Houston rejected the actions of the Texas Secession Convention, believing it had overstepped its authority in becoming a member state of the newly formed Confederacy.

Hood's men suffered severe casualties in a number of fights, most notably at the Battle of Antietam, where they faced off with Wisconsin's Iron Brigade, and at Gettysburg, where they assaulted Houck's Ridge and then Little Round Top.

[citation needed] Formed in 1862, under command of Major General John George Walker it fought in the Western Theater and the Trans-Mississippi Department, and was considered an elite backbone of the army.

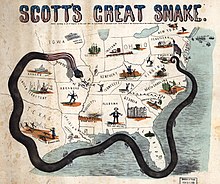

Under the Anaconda Plan, the Union Navy blockaded the principal seaport, Galveston and the entire Gulf and Southern borders, for four years, and federal troops occupied the city for three months in late 1862.

President Lincoln referred to the strategic importance of this economic movement through the Rio Grande to the Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton in 1863 stating, "no local object is now more desirable.

"[32] The Rio Grande Expedition, led by General Nathaniel P. Banks, was then sent forth to secure the ports near Brownsville and pushed 100 miles in-land, in order to impede the flow of cotton and deny freedom of movement.

At the Second Battle of Sabine Pass, a small garrison of 46 Confederates from the mostly-Irish Davis Guards under Lt. Richard W. Dowling, 1st Texas Heavy Artillery, defeated a much larger Union force from New Orleans under Gen. William B. Franklin.

Skilled gunnery by Dowling's troops disabled the lead ships in Franklin's flotilla, prompting the remainder—4,000 men on 27 ships—to retreat back to New Orleans.

This victory against such overwhelming odds resulted in the Confederate Congress passing a special resolution of recognition, and the only contemporary military decoration of the South, the Davis Guards Medal.

[33] CSA President Jefferson Davis stated, "Sabine Pass will stand, perhaps for all time, as the greatest military victory in the history of the world."

Upon his arrival in Houston from Shreveport, the general called a court of inquiry to investigate the "causes and manner of the disbandment of the troops in the District of Texas, New Mexico and Arizona."