Text-based user interface

From text application's point of view, a text screen (and communications with it) can belong to one of three types (here ordered in order of decreasing accessibility): Under Linux and other Unix-like systems, a program easily accommodates to any of the three cases because the same interface (namely, standard streams) controls the display and keyboard.

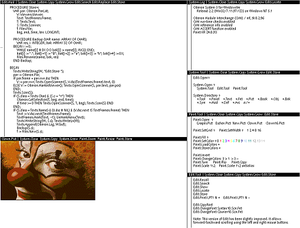

Escape sequences may be supported for all three cases mentioned in the above section, allowing arbitrary cursor movements and color changes.

However, programmers soon learned that writing data directly to the screen buffer was far faster and simpler to program, and less error-prone; see VGA-compatible text mode for details.

Most often those programs used a blue background for the main screen, with white or yellow characters, although commonly they had also user color customization.

The advent of the curses library with Berkeley Unix created a portable and stable API for which to write TUIs.

This can be seen in text editors such as vi, mail clients such as pine or mutt, system management tools such as SMIT, SAM, FreeBSD's Sysinstall and web browsers such as lynx.

The free Emacs text editor can run a shell inside of one of its buffers to provide similar functionality.

The free Vim and Neovim text editors have terminal windows (simulating xterm).

The feature is intended for running jobs, parallel builds, or tests, but can also be used (with window splits and tab pages) as a lightweight terminal multiplexer.

Unlike most other text-based user interfaces, Oberon does not use a text-mode console or terminal, but requires a large bit-mapped display, on which text is the primary target for mouse clicks.

Text displayed anywhere on the screen can be edited, and if formatted with the required command syntax, can be middle-clicked and executed.

[4] Oberon's UI influenced the design of the Acme text editor and email client for the Plan 9 from Bell Labs operating system.