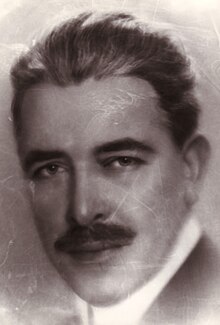

Abdolhossein Teymourtash

Abdolhossein Teymourtash (Persian: عبدالحسین تیمورتاش; 25 September 1883 – 3 October 1933) was an influential Iranian statesman who served as the first minister of court of the Pahlavi dynasty from 1925 to 1932, and is credited with playing a crucial role in laying the foundations of modern Iran in the 20th century.

His father, Karimdad Khan Nardini (Moa'zes al Molk), was a major landowner with extensive landholdings in Khorasan, Iran's northern province neighbouring the then Imperial Russia's Central Asia (now Turkmenistan).

While the rank and file of this particular society consisted mainly of lesser tradesman and poorer people, and included amongst its active membership very few educated notables, Teymourtash demonstrated his progressive tendencies by developing a strong affinity for the constitutional ideals and thrust of this gathering and assumed a leading role in the group.

Teymourtash's active involvement in constitutional gatherings led, in due course, to his appointment as chief of staff of the populist constitutionalist forces resisting the reigning monarch's decision to storm the buildings of Parliament.

His governorship of Gilan was to prove particularly noteworthy given the reality that his primary mandate was to counter secessionist forces in that province led by Mirza Kuchak Khan who received assistance from the new Bolshevik Government in the neighbouring Soviet Union.

Given Teymourtash's concern with protecting the territorial integrity of Iran from the secessionist troops led by Mirza Kuchak Khan, upon his recall to Tehran, along with Seyyed Zia'eddin Tabatabaee, he approached the British legation in the capital to solicit their support to resist the insurgents in the North.

On February 21, 1921, a group of Anglophile political activists led by Seyyed Zia'eddin Tabatabaee, the rising young journalist, succeeded in plotting a coup that toppled the Iranian Government, while vowing to preserve the Qajar monarchy.

Reza Khan had successfully consolidated his hold over this cavalry unit when its Tsarist commanding officers departed Iran due to the revolutionary upheaval and the ensuing Civil War that engulfed their country.

Soon after being released, Teymourtash returned to Tehran and was appointed Minister of Justice in the cabinet of Hassan Pirnia ("Moshir od-Dowleh"), with a mandate to initiate the process of modernizing the court system in Iran based on the French judicial model.

Among his most notable accomplishments in his capacity as Minister of Public works in 1924 made the far reaching decision to draft a detailed proposal to the Iranian Parliament in 1924 introducing a tax on tea and sugar to finance the construction of a Trans-Iranian Railway, a project which was ultimately completed twelve years later in 1937.

Teymourtash's abiding interest in literature would in fact lead him to advocate in favour of securing government funds to allow Allameh Ghazvini[7] to undertake an elaborate project to copy old Persian manuscripts available in European library collections.

The funding permitted Allameh Ghazvini to spend many years visiting libraries in London, Paris, Leningrad, Berlin, and Cairo where he secured copies of rare manuscripts which he subsequently forwarded to Tehran to be utilized by Iranian scholars.

In other instances, Teymourtash used his political influence to assist intellectuals and writers such as his interventions to ensure that the renowned historian Ahmad Kasravi[8] would be spared harassment by the government apparatus while undertaking research, and his success in securing a seat for noted poet Mohammad Taghi Bahar to the 5th Majles from Bojnourd district which he had himself previously represented.

The society spurred considerable interest by western orientalists to undertake archaeological excavations in Iran, and lay the foundation for the construction of a mausoleum to honour Ferdowsi in 1934 and of Hafez in 1938, to name a few of its more notable early achievements.

It was Teymourtash's appointment as Minister of Court in 1925 that proved invaluable in allowing him to demonstrate his prowess as a formidable administrator, and to establish his reputation as an indefatigable statesman intent on successfully laying the foundations of modern Iran.

Moreover, in the period following the Coup of 1921, Teymourtash had been instrumental in successfully navigating legislation through the Iranian parliament whereby it became possible for Reza Khan to assume full jurisdiction over Iran's defence apparatus in his capacity as Commander in Chief.

Apart from appreciating Teymourtash's strong grasp of the parliamentary and legislative process, it is likely that the decision to appoint him as his first Minister of Court was animated by Reza Shah's keen interest in selecting an urbane individual familiar with diplomatic protocol who could impress foreign capitals, as well as an energetic and workaholic reformer capable of introducing discipline to the administration of government.

Lacking any semblance of a formal education, the new Reza Shah maintained his firm grip over all matters pertaining to the army and internal security, while Teymourtash was left a free hand to devise blueprints for modernizing the country, orchestrating the political implementation of much needed bureaucratic reforms, and acting as the principal steward of its foreign relations.

In 1926 Clive, the British diplomat, wrote to London about mental malaise evident in Reza Shah by stating "his energy appears for the moment to have deserted him; his faculties have been clouded by the fumes of opium, which have distorted his judgement and induced long spells of sullen and secretive lethargy punctuated by nightmare suspicions or by spasms of impulsive rage".

In the following year, inspired by the French Lycee model, a uniform curriculum was established for high schools, and the Ministry of Education began publishing academic textbooks free of charge for all needy students and at cost for others.

Teymourtash's success in these endeavours owed much to his ability to methodically secure agreements from the less obstinate countries first so as to gain greater leverage against the holdouts, and to even intimate that Iran was prepared to break diplomatic relations with recalcitrant states if need be.

Apart from encouraging the press to draft editorials criticizing the terms of the D'Arcy concession, he arranged to dispatch a delegation consisting of Reza Shah, and other political notables and journalists to the close vicinity of the oilfields to inaugurate a newly constructed road, with instructions that they refrain from visiting the oil installation in an explicit show of protest.

He married his daughter, he put his boy to school [Harrow], he met the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, a change took place in our government, and in the midst of all this maze of activities we reached a tentative agreement on the principles to be included in the new document, leaving certain figures and the lump sum to be settled at a later date."

Matters came to a head in 1931, when the combined effects of overabundant oil supplies on the global markets and the economic destabilization of the Depression, led to fluctuations which drastically reduced annual payments accruing to Iran to a fifth of what it had received in the previous year.

Rejecting the cancellation, the British government espoused the claim on behalf of APOC and brought the dispute before the Permanent Court of International Justice at the Hague, asserting that it regarded itself "as entitled to take all such measures as the situation may demand for the Company's protection."

The principal reason for Teymourtash's dismissal very likely had to do with British machinations to ensure that the able Minister of Court was removed from heading Iranian negotiations on discussions relating to a revision of the terms of the D'Arcy concession.

It extended the life of the D'Arcy concession by an additional thirty-two years, negligently allowed APOC to select the best 100,000 square miles (260,000 km2), the minimum guaranteed royalty was far too modest, and in a fit of carelessness the company's operations were exempted from import or customs duties.

While it was not uncommon for Reza Shah to imprison or kill his previous associates and prominent politicians, most notably Firouz Mirza Nosrat-ed-Dowleh Farman Farmaian III and Sardar Asad Bakhtiar, the decision to impose severe collective punishment on Teymourtash's family was unprecedented.

In Princess Ashraf Pahlavi's candid memoirs, entitled Faces in a Mirror, and released after the Revolution, the Shah's sister reveals, "I was attracted to Houshang's tall good looks, his flamboyant charm, the sophistication he had acquired during his years at school in England.

In the concluding paragraph the American diplomat noted, "Albeit he had enemies and ardent ones, I doubt that anyone could be found in Persia having any familiarity with the deeds and accomplishments of Teymourtache who would gainsay his right to a place in history as perhaps the most commanding intellect that has arisen in the country in two centuries".