Thai Forest Tradition

He strove for a revival of the Early Buddhism, insisting on a strict observance of the Buddhist monastic code known as the Vinaya and teaching the practice of jhāna and the realization of nibbāna.

Initially, Ajahn Mun's teachings were met with fierce opposition, but in the 1930s his group was acknowledged as a formal faction of Thai Buddhism, and in the 1950s the relationship with the royal and religious establishment improved.

[citation needed] Before authority was centralized in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the region known today as Thailand was a kingdom of semi-autonomous city-states (Thai: mueang).

[citation needed] In the 1820s young Prince Mongkut (1804–1866), the future fourth king of the Rattanakosin Kingdom (Siam), was ordained as a Buddhist monk before rising to the throne later in his life.

He was also concerned about the authenticity of the ordination lineages, and the capacity of the monastic body to act as an agent that generates positive kamma (Pali: puññakkhettam, meaning "merit-field").

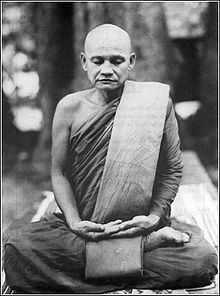

[web 2][note 3] Ajahn Mun (1870–1949) went to Wat Liap monastery immediately after being ordained in 1893, where he started to practice kasina-meditation, in which awareness is directed away from the body.

In an introduction to the Buddhist monastic code written by Wachirayan, he stated that the rule forbidding monks to make claims to superior attainments was no longer relevant.

[10] As his mind gained more inner stability, he gradually headed towards Bangkok, consulting his childhood friend Chao Khun Upali on practices pertaining to the development of insight (Pali: paññā, also meaning "wisdom" or "discernment").

He then left for an unspecified period, staying in caves in Lopburi, before returning to Bangkok one final time to consult with Chao Khun Upali, again pertaining to the practice of paññā.

After medicines failed to remedy his illness, Ajahn Mun ceased to take medication and resolved to rely on the power of his Buddhist practice.

Ajahn Mun investigated the nature of the mind and this pain, until his illness disappeared, and successfully coped with visions featuring a club-wielding demon apparition who claimed he was the owner of the cave.

According to forest tradition accounts, Ajahn Mun attained the noble level of non-returner (Pali: "anagami") after subduing this apparition and working through subsequent visions he encountered in the cave.

Chao Khun Upali held Ajahn Mun in high esteem, which would be a significant factor in the subsequent leeway that state authorities gave him and his students.

This event marked a turning point in relations between the Dhammayut administration and the Forest Tradition, and interest continued to grow as a friend of Ajahn Maha Bua's named Nyanasamvara rose to the level of somdet and later the Sangharaja of Thailand.

Additionally, the clergy who had been drafted as teachers from the Fifth Reign onwards were now being displaced by civilian teaching staff, which left the Dhammayut monks with a crisis of identity.

[19][20] In the tradition's beginning the founders famously neglected to record their teachings, instead wandering the Thai countryside offering individual instruction to dedicated pupils.

Forest monasteries in the South Ajahn Buddhadasa Bhikkhu (May 27, 1906 - May 25, 1993) became a Buddhist monk at Wat Ubon, Chaiya, Surat Thani in Thailand on July 29, 1926, when he was twenty years old, in part to follow the tradition of the day and to fulfill his mother’s wishes.

After he finished learning the Pali language, he realized that living in Bangkok was not suitable for him because monks and people there did not practice to achieve the heart and core of Buddhism.

Then he established Suanmokkhabālārama (The Grove of the Power of Liberation) in 1932 which is the mountain and forest for 118.61 acres at Pum Riang, Chaiya district, Surat Thani Thailand.

On October 20, 2005, The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) announced praise to “Buddhadasa Bhikkhu”, an important person in the world and celebrated the 100th anniversary on May 27, 2006.

So, he was the practitioner of a great Thai Forest Tradition who practiced well and spread Dhammas for people around the world to realize the core and heart of Buddhism.

In 1975, Ajahn Chah and Sumedho founded Wat Pah Nanachat, an international forest monastery in Ubon Ratchatani which offers services in English.

By this time, the Forest Tradition's authority had been fully routinized, and Ajahn Maha Bua had grown a following of influential conservative-loyalist Bangkok elites.

This led to Ajahn Maha Bua's striking back with heavy criticism, which is cited as a contributing factor to the ousting of Chuan Leekpai and the election of Thaksin Shinawatra as prime minister in 2001.

On the subject, Ajahn Maha Bua said that "it is clear that combining the accounts is like tying the necks of all Thais together and throwing them into the sea; the same as turning the land of the nation upside down.

[25] Throughout the 2000s, Ajahn Maha Bua was accused of political leanings—first from Chuan Leekpai supporters, and then receiving criticism from the other side after his vehement condemnations of Thaksin Shinawatra.

According to the Thai Forest Tradition's exposition, awareness of the deathless is boundless and unconditioned and cannot be conceptualized, and must be arrived at through mental training which includes states of meditative concentration (Pali: jhana).

Forest teachers thus directly challenge the notion of "dry insight"[29] (insight without any development of concentration) and teach that nibbāna must be arrived at through mental training which includes deep states of meditative concentration (Pali: jhāna), and "exertion and striving" to "cut" or "clear the path" through the "tangle" of defilements, setting awareness free,[30][31] and thus allowing one to see them clearly for what they are, eventually leading one to be released from these defilements.

[note 15] The primal or original mind in itself is however not considered to be equivalent to the awakened state but rather as a basis for the emergence of mental formations,[42] it is not to be confused for a metaphysical statement of a true self[43][44] and its radiance being an emanation of avijjā it must eventually be let go of.

The twelve nidanas describe how, in a continuous process,[34][note 17] avijja ("ignorance," "unawareness") leads to the mind's preoccupation with its contents and the associated feelings that arise from sense-contact.