Apollo Theater

[54] Among the operators of these early theaters were theatrical producers Jules Hurtig and Harry Seamon, who leased the Harlem Music Hall at 209 West 125th Street in 1897.

[132] Because the Apollo did not have wealthy backers, in contrast to venues such as Carnegie Hall and the Metropolitan Opera House, its income depended heavily on the success or failure of each week's show.

[138] The Apollo Theatre had vigorous competition from other venues, namely Leo Brecher's Harlem Opera House and Frank Schiffman's Lafayette.

[156] During World War II, the theater offered 35 free tickets to members of the U.S. armed forces, and entertainers at the Apollo performed at the nearby Harlem Defense Recreation Center on Tuesday nights.

The project cost $45,000 and entailed new sound systems, a remodeled orchestra pit, women's and men's lounges, a staff recreation room, and modifications to decorations.

[171] Even so, many popular black artists such as Eartha Kitt and Sammy Davis Jr. regularly returned for "the folks who can't make it downtown".

[191] To raise money, Robert Schiffman wanted to show first runs of films featuring black actors but faced competition from other Manhattan theaters.

[18] The Internal Revenue Service raided the theater in November 1979 after finding that the new owners had failed to pay tens of thousands of dollars in taxes over the two preceding years.

[228][229] The original reopening date of July 1982 was postponed due to the complexity of the project,[230] and the state government expressed concerns that Sutton could not afford to pay for increasing renovation costs.

[238] The renovation was restarted in May 1983 after the state UDC agreed to give the theater $2.5 million;[239][240] without this funding, the Apollo Theatre Investor Group would have canceled the project entirely.

[243] By October 1985, the theater had closed temporarily to accommodate the construction of the recording studio;[261] the New York Amsterdam News reported two months later that the work would last until late 1986.

[271] Three hundred churches with black congregations also donated to the Apollo,[272] and State Assembly member Geraldine L. Daniels asked the Recording Academy to consider hosting the Grammy Awards there.

[287] The ATF began raising $30 million for the theater in the late 1990s,[181][48] but the city and state governments refused to issue $750,000 in grants unless the foundation could provide financial statements.

The ATF's board hired Caples Jefferson Architects to design the renovation, and the New York Landmarks Conservancy created a report on the theater's condition.

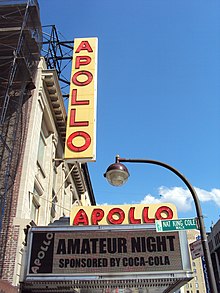

[314][316] The Coca-Cola Company signed a ten-year sponsorship agreement with the ATF that August,[317] and the Dance Theatre of Harlem also partnered with the Apollo that year.

[320] Johnson resigned in September 2002 after the ATF's board canceled plans to lease the Victoria and approved a smaller renovation project costing $53–54 million.

[311][334] Although the Apollo was receiving many grassroots donations, Procope had decided to focus on expanding the theater's programming;[334] it sold 400,000 tickets per year at the time.

[371] Winners have included Pearl Bailey,[372][38] Thelma Carpenter,[383] Ella Fitzgerald,[202][384] The Jackson 5,[385] Sarah Vaughan,[38][386] Frankie Lymon and The Teenagers,[32][372] King Curtis, Wilson Pickett, Ruth Brown, Gladys Knight, Smokey Robinson,[38] The Ronettes, The Isley Brothers, Stephanie Mills,[372] Leslie Uggams, Sammy Davis Jr., Billie Holiday, and Dionne Warwick.

[388] The ATF formed a partnership with the Verizon Foundation in 2007 to teach local students about the theater's history,[389] and it began hosting the Master Class Series for performers in 2012.

[394] Apollo New Works is intended to showcase musical, theatrical, or dance performances by black artists; a set of artists-in-residence is selected every year.

[426] After the Apollo was renovated in the 1980s, it hosted such diverse acts as the New York Philharmonic,[427] rock and soul band Hall & Oates,[428] and pop musician Prince.

[414][407] The theater hosted dancers such as Bunny Briggs and Babe Lawrence during the mid-20th century,[414] as well as Cholly Atkins, Bill Bailey, Honi Coles, The Four Step Brothers, and Tip, Tap and Toe.

[464][465] The theater has also hosted other plays, musicals, and revues in the 21st century, such as The Jackie Wilson Story in 2003[466] and Apollo Club Harlem in 2013,[467] as well as James Brown: Get on the Good Foot, also in 2013.

In the theater's early years, these included Butterbeans and Susie, Moms Mabley, Dewey "Pigmeat" Markham, Redd Foxx, Dick Gregory, Richard Pryor, Nipsey Russell, Slappy White, Flip Wilson,[118][407] Godfrey Cambridge,[118] Timmie Rogers,[469] and Stump and Stumpy.

[414] Among the theater's most popular comedy acts in the mid-20th century were Mabley, who satirized Jim Crow laws in her shows, and Rogers, who performed song-and-dance routines.

When Schiffman operated the Apollo, he frequently rented the theater for meetings on topics concerning black Americans, including discussions of civil rights and employment.

[176][503] Civil-rights leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr., A. Philip Randolph, and Bayard Rustin, as well as organizations like the NAACP and the Congress of Racial Equality, hosted speeches at the Apollo during the 1950s and 1960s.

[507]The Apollo has hosted memorial services, including those of civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. in 1972,[508] James Brown in 2007, and Michael Jackson in 2009.

[136] The Los Angeles Sentinel wrote in 1982 that "the Apollo has had a significant impact on the careers of virtually every black performer who has played there",[118] and the New York Amsterdam News said the next year that the theater "led the way in the presentation of swing, bebop, rhythm and blues, modern jazz, commercially produced gospel, soul and funk".

[521] The Wall Street Journal wrote in 2011: "You'd be hard-pressed to find a major African-American entertainer, singer, bandleader, dancer or comic who didn't appear there.