The Assault on Truth

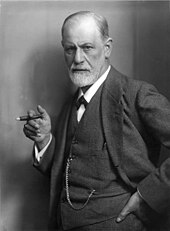

The Assault on Truth: Freud's Suppression of the Seduction Theory is a book by the former psychoanalyst Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson, in which the author argues that Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, deliberately suppressed his early hypothesis, known as the seduction theory, that hysteria is caused by sexual abuse during infancy, because he refused to believe that children are the victims of sexual violence and abuse within their own families.

It was condemned by reviewers within the psychoanalytic profession, and came to be seen as the latest in a series of attacks on psychoanalysis and an expression of a widespread "anti-Freudian mood."

He has also been criticized for his discussion of Freud's treatment of his patient Emma Eckstein, for suggesting that children are by nature innocent and asexual, and for taking part in a reaction against the sexual revolution.

Masson argues that the accepted account of the way in which, Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, abandoned his seduction theory is incorrect.

[1] According to the historian Roy Porter, Masson, formerly a Sanskrit professor, retrained as a psychoanalyst, and in the 1970s found support within the psychoanalytic profession in the United States.

The journalist Janet Malcolm published two articles about the controversy, later issued as a book, In the Freud Archives (1984), in The New Yorker.

[2] Many of Masson's conclusions had earlier been reached by Florence Rush, who made a public presentation of them in 1971 in New York (forming The Freudian Coverup theory).

[7] In New Statesman and Society, Jenny Turner dismissed the book, accusing Masson of spite, misreadings, and making inept arguments.

He was unconvinced by Masson's attempts to use evidence such as Freud's treatment of Eckstein and a paper by Ferenczi to support his views.

While he credited Masson with making contributions to the history of psychoanalysis, he wrote that Masson's main argument has not convinced either psychoanalysts or the majority of Freud's critics, since scholars have disputed that Freud formulated the seduction theory on the basis of memories of childhood seduction provided by his patients.

He blamed Masson for encouraging the spread of the recovered memory movement by implying that most or all serious cases of neurosis are caused by child sexual abuse, that psychoanalysts were collectively engaged in a massive denial of this fact, and that an equally massive collective effort to retrieve painful memories of incest was required.

[28] Breger wrote that Masson provided valuable information on the later life of Eckstein and was correct to question the accepted account of the abandonment of the seduction theory.

[38] The book received positive reviews from the psychiatrist Judith Lewis Herman in The Nation and Pierre-E. Lacocque in the American Journal of Psychotherapy.

[43] Other reviews included those by the historian Paul Robinson in The New Republic,[44] Elaine Hoffman Baruch in The New Leader,[45] Michael Heffernan in New Statesman,[46] Kenneth Levin in the American Journal of Psychiatry,[47] Thomas H. Thompson in North American Review,[48] F. S. Schwarzbach in The Southern Review,[49] the psychiatrist Bob Johnson in New Scientist,[50] Thelma Oliver in the Canadian Journal of Political Science,[51] the psychoanalyst Donald P. Spence in the American Journal of Orthopsychiatry,[52] Gary Alan Fine in Contemporary Sociology,[53] D. A. Strickland in the American Political Science Review,[54] Franz Samelson in Isis,[55] and the philosopher John Oulton Wisdom in Philosophy of the Social Sciences.

[31] Mitchell wrote that while Masson provided fascinating excerpts from important documents relating to Freud that had previously been carefully guarded, his conclusions were "characterized by a bitter tendentiousness, simplistic rhetoric, and a serious lack of comprehension of the subtleties of later psychoanalyic theorizing.

[33] Rycroft maintained that because Masson chose to present the book as a polemical attack on Freud, it did not qualify as a contribution to the early history of psychoanalysis.

He criticized Masson for wanting to re-establish the truth of the seduction theory without presenting evidence that it was actually correct, and concluded that the book was "distasteful, misguided, and at times silly.

[37] Birken argued that Masson's attempt to revive the seduction theory was more important than his speculations about why Freud abandoned it.

She credited Masson with demonstrating that once Freud abandoned the seduction theory, any further consideration of its possible validity became "a heresy" within psychoanalysis.

She also praised Masson for documenting Freud's attempt to stop Ferenczi from publicizing his rediscovery of "the kind of clinical data on which the seduction theory was based".