The Cerdá Plan

It was created by the civil engineer Ildefons Cerdà and its approval was followed by a strong controversy for having been imposed by the government of the Kingdom of Spain against the plan of Antoni Rovira i Trias who had won a competition of the Barcelona City Council.

Despite the decision made by Bishop Pablo de Sichar[3] in 1819 to hold burials in the Poblenou cemetery, its operation was not consolidated until the middle of the 19th century.

[9] In 1844, Jaime Balmes joined, from the pages of La Sociedad, the protests contradicting the theories of military strategic value defended by General Narváez.

More than ten years passed until the Barcelona City Council approved a project prepared by its secretary Manuel Durán y Bas, which was sent to the Madrid government on 23 May 1853, with the unanimous signature of the consistory with its mayor, Josep Beltran i Ros at the head.

Madoz became civil governor of Barcelona for barely seventy-five days when he became Minister of Finance of the progressive government, from where he urged the disentailment and promulgated a royal order that would put an end to the confrontations between the City Council and the Ministry of War.

In 1844 Miquel Garriga i Roca offered himself to the Barcelona City Council as municipal architect for the planning of the expansion, with a proposal focused on ornamental beautification operations.

In 1846 Antoni Rovira i Trias published in the Boletín Enciclopédico de Nobles Artes a proposal for the formation of a geometric plan of Barcelona.

Cerdá was a person very sensitive to the hygienist currents, he applied his knowledge to develop, on his own, a Monograph of the working class (1856), a complete and deep statistical analysis of the living conditions within the city walls based on social, and economic, and nutritional aspects.

The diagnosis was clear: the city was not suitable for "the new civilization, characterized by the application of steam energy in industry and the improvement of mobility[13] and communication" (the optical telegraph was the other relevant invention).

One of the most important features of Cerdà's proposal, what makes him stand out in the history of urban planning, is the search for coherence to account for the contradictory requirements of a complex agglomeration.

The city council reacted immediately by calling on 15 April a public competition on plans for the widening with a deadline of 31 July, although it was postponed to 15 August.

Meanwhile, Cerdá wasted no time, finished his project, and showed it -to gain support in Madrid- to Madoz, Laureano Figuerola, and the general director of Public Works, the Marquis of Corvera.

These plans, unlike the one proposed by Cerdá, occupied a smaller area and were intended to accommodate fewer people, which is logical if we think that they obeyed the objectives of the bourgeoisie to reinforce social segregation.

[18] According to the municipal council, the winning project was a proposal by Antoni Rovira based on a circular mesh that enveloped the walled city and grew radially, harmoniously integrating the surrounding villages.

[21] After the unappealable approval of the central government, on 4 September 1860, Queen Isabella II laid the first stone of the Eixample in the current Plaça de Catalunya.

But the great interest ended up being detrimental to the initial plan, and the construction fever contributed to the progressive reduction of green spaces and facilities.

The "intervías" (island, block, or square) are the spaces of private life, where multi-family buildings are gathered in two rows around an inner courtyard through which all dwellings (without exception) receive sunshine, natural light, ventilation, and joie de vivre, as demanded by the hygienist movements.

However, the enormous advantages of the city force to compact, the essence of the urban fact, and to design a house that allows it to fit in a multi-family building in height, and enjoy, thanks to careful distribution, double ventilation from the street, and the inner courtyard of the "block".

[14] In the plan proposed by Cerdá for the city, the optimism and unlimited foresight of growth, the programmed absence of a privileged center, and its mathematical, geometric character and scientific vision stand out.

[15] Obsessed by the hygienist aspects that he had studied in depth and having wide freedom to configure the city since the plain of Barcelona had almost no construction, his structure takes maximum advantage of the direction of the winds to facilitate oxygenation and cleaning of the atmosphere.

He defined an unusual width of streets, partly to escape from the inhuman density that the city lived, but also thinking of a motorized future with its own spaces separated from those of social coexistence that reserved them for the interior areas.

He incorporated the layout of railway lines that had influenced his vision of the future when he visited France, although he is aware that these have to go underground, and he was concerned that each neighborhood should have an area dedicated to public buildings.

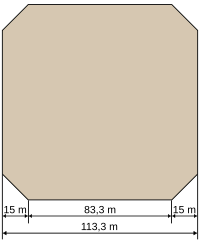

Cerdà, 1851The most outstanding formal solution of the project was the incorporation of the block; its crucial and singular form concerning other European cities is marked by its square structure of 113.33 meters with 45º chamfers.

[1] The engineer's vision was of growth and modernity; his genius allowed him to anticipate future urban traffic conflicts 30 years before the invention of the automobile.

The links with these nuclei were not foreseen, except for Sant Andreu de Palomar, bordered by Meridiana Avenue, and the canals of human tradition were ignored.

The first generalization of the use of the chamfer or ochava was given throughout Argentina as a result of the decree of the Minister of Government and later President Bernardino Rivadavia "Edificios y calles de las ciudades y pueblos" ("Buildings and streets of cities and towns") of 14 December 1821.

The anti-authoritarian, anti-hierarchical, egalitarian[29] and rationalist character of the plan clashed directly with the vision of the bourgeoisie who preferred to have Paris or Washington as a reference for a new city with a more particularist architecture.

[30] In 1905, 50 years after the approval of the plan, Prat de la Riba expressed his deep indignation "against the governments that imposed on us the monotonous and shameful grid" instead of the system he dreamed of a city radiated from the old historical capital.