Chichimeca War

The Chichimeca War is recorded as the longest and most expensive military campaign confronting the Spanish Empire and indigenous people in Aridoamerica.

The forty-year conflict was settled through several peace treaties driven by the Spaniards which led to the pacification and, ultimately, the streamlined integration of the native populations into the New Spain society.

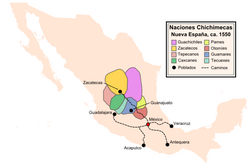

The war was fought in what are the present-day Mexican states of Zacatecas, Guanajuato, Aguascalientes, Jalisco, Queretaro, and San Luis Potosí.

The dream of quick wealth caused a large number of Spaniards to migrate from southern Mexico to the present-day city of Zacatecas in the heartland of La Gran Chichimeca.

[4] The Chichimecas were nomadic and semi-nomadic people who occupied the large desert basin stretching from present day Saltillo and Durango in the north to Querétaro and Guadalajara in the south.

Within this area of about 160,000 square kilometres (62,000 sq mi), the Chichimecas lived primarily by hunting and gathering, especially mesquite beans, the edible parts of the agave plants, and the fruit (tunas) and leaves of cactus.

The characteristics most noted about them by the Spanish was that both women and men wore little clothing, grew their hair long, and painted and tattooed their bodies.

[10] The Guamares and the mestizo population of Dolores Hidalgo, on the silver road to San Miguel de Allende, also initiated the Mexican War for Independence, then shortly after sent a battalion of reinforcements to the Battle of Puebla during the French intervention in Mexico.

Despite the fragility of the obsidian arrows they had excellent penetrating qualities, even against Spanish armor which was de rigueur for soldiers fighting the Chichimeca.

"His long use of the food native to the Gran Chichimeca gave him far greater mobility than the sedentary invader, who was tied to domesticated livestock, agriculture, and imported supplies.

The Chichimeca could and did cut off these supplies, destroy the livestock, and thus paralyze the economic and military vitality of the invaders; this was seldom possible in reverse" (Powell 44).

They had no shortage of raiding parties because of the highly valued supplies attracting warriors from far off allowing for the highest quality of trade goods.

"He [The Chichimeca] sent spies into Spanish towns for appraisal of the enemy's plans and strength; he developed a far-flung system of lookouts and scouts (atalays); and, in major attacks, settlements were softened by preliminary and apparently systematic killing and stealing of horses and other livestock, this being an attempt, sometimes successful, to change his intended victim from horseman to foot soldier" (Powell 46).

In 1551 the Guachichile and Guamares joined in, killing 14 Spanish soldiers at an outpost of San Miguel de Allende and forcing its abandonment.

Some crucial raids of the early years of the war took place in 1553 and 1554 when many wagon trains on the road to Zacatecas were attacked, all the Spanish en route were killed, and the very substantial sums of 32,000 and 40,000 pesos in goods taken or destroyed.

One of the priorities of the Spaniards throughout the war was to keep the roads open to Zacatecas and the silver mines – especially the Camino Real from San Miguel de Allende.

The Viceroy, Alvaro Manrique de Zuniga, followed this idea in 1586 with a policy of removing many Spanish soldiers from the frontier as they were considered more a provocation than a remedy.

Beginning in 1590 and continuing for several decades the Spanish implemented the "Purchase for Peace" program by sending large quantities of goods northward to be distributed to the Chichimecas.

[16] The next step, in 1591, was for a new Viceroy, Luis de Velasco, with help from others such as Caldera, to persuade 400 families of Tlaxcalan Indians, old allies of the Spanish, to establish eight settlements in Chichimeca areas.

In return for moving to the frontier, the Tlaxcalans extracted concessions from the Spanish, including land grants, freedom from taxes, the right to carry arms, and provisions for two years.

The Spanish also took steps to curb slavery on Mexico's northern frontier by ordering the arrest of members of the Carabajal family and Gaspar Castaño de Sosa.

The Spanish policy evolved to make peace with the Chichimecas had four components: negotiation of peace agreements; welcoming, instead of forcing, conversion to Catholicism; encouraging native allies to settle the frontier to serve as examples and role models; and providing food, other commodities, and tools to potentially hostile natives.

The principal components of the policy of purchase for peace would continue for nearly three centuries and would not be as successful, as later threats from hostile natives such as Apaches and Comanches would demonstrate.

Over time most of the Chichimeca people transformed their ethnic identities and absorbed into the Catholic population and more assimilated in mainstream society before and during the Mexican War of Independence.

Large portions of the Guachihil population from La Montesa to Milagros migrated to the larger cities of Zacatecas or Aguascalientes and to the territories of California, Colorado, and Texas.