Critique of Pure Reason

Knowledge gained a posteriori through the senses, Kant argues, never imparts absolute necessity and universality, because it is possible that we might encounter an exception.

"[8] It is a "matter of life and death" to metaphysics and to human reason, Kant argues, that the grounds of this kind of knowledge be explained.

"I freely admit that it was the remembrance of David Hume which, many years ago, first interrupted my dogmatic slumber and gave my investigations in the field of speculative philosophy a completely different direction.

He demonstrated this with a thought experiment, showing that it is not possible to meaningfully conceive of an object that exists outside of time and has no spatial components and is not structured following the categories of the understanding (Verstand), such as substance and causality.

The human mind is incapable of going beyond experience so as to obtain a knowledge of ultimate reality, because no direct advance can be made from pure ideas to objective existence.

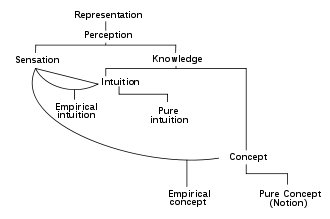

Kant's metaphysical system, which focuses on the operations of cognitive faculties (Erkenntnisvermögen), places substantial limits on knowledge not found in the forms of sensibility (Sinnlichkeit).

It is because he takes into account the role of people's cognitive faculties in structuring the known and knowable world that in the second preface to the Critique of Pure Reason Kant compares his critical philosophy to Copernicus' revolution in astronomy.

[17] Kant's transcendental idealism should be distinguished from idealistic systems such as that of George Berkeley which deny all claims of extramental existence and consequently turn phenomenal objects into things-in-themselves.

While Kant claimed that phenomena depend upon the conditions of sensibility, space and time, and on the synthesizing activity of the mind manifested in the rule-based structuring of perceptions into a world of objects, this thesis is not equivalent to mind-dependence in the sense of Berkeley's idealism.

Kant's revolutionary claim is that the form of appearances—which he later identifies as space and time—is a contribution made by the faculty of sensation to cognition, rather than something that exists independently of the mind.

The Analytic Kant calls a "logic of truth";[38] in it he aims to discover these pure concepts which are the conditions of all thought, and are thus what makes knowledge possible.

"[40] Kant's investigations in the Transcendental Logic lead him to conclude that understanding and reason can only legitimately be applied to things as they appear phenomenally to us in experience.

In the Metaphysical Deduction, Kant aims to derive twelve pure concepts of the understanding (which he calls "categories") from the logical forms of judgment.

Again, Kant, in the "Transcendental Logic", is professedly engaged with the search for an answer to the second main question of the Critique: How is pure physical science, or sensible knowledge, possible?

[49][verification needed] One of the ways that pure reason erroneously tries to operate beyond the limits of possible experience is when it thinks that there is an immortal Soul in every person.

In order for humans to behave properly, they can suppose that the soul is an imperishable substance, it is indestructibly simple, it stays the same forever, and it is separate from the decaying material world.

Kant called this Supreme Being, or God, the Ideal of Pure Reason because it exists as the highest and most complete condition of the possibility of all objects, their original cause and their continual support.

If man finds that the idea of God is necessarily involved in his self-consciousness, it is legitimate for him to proceed from this notion to the actual existence of the divine being.

[62] The physico-theological proof of God's existence is supposed to be based on a posteriori sensed experience of nature and not on mere a priori abstract concepts.

In abandoning any attempt to prove the existence of God, Kant declares the three proofs of rational theology known as the ontological, the cosmological and the physico-theological as quite untenable.

Far from advocating for a rejection of religious belief, Kant rather hoped to demonstrate the impossibility of attaining the sort of substantive metaphysical knowledge (either proof or disproof) about God, free will, or the soul that many previous philosophers had pursued.

Kant argues against the polemic use of pure reason and considers it improper on the grounds that opponents cannot engage in a rational dispute based on a question that goes beyond the bounds of experience.

By attempting to directly prove transcendental assertions, it will become clear that pure reason can gain no speculative knowledge and must restrict itself to practical, moral principles.

Aristotle's imperfection is apparent from his inclusion of "some modes of pure sensibility (quando, ubi, situs, also prius, simul), also an empirical concept (motus), none of which can belong to this genealogical register of the understanding."

Feder believed that Kant's fundamental error was his contempt for "empirical philosophy", which explains the faculty of knowledge according to the laws of nature.

The philosopher Adam Weishaupt, founder and leader of the secret society the Illuminati, and an ally of Feder, also published several polemics against Kant, which attracted controversy and generated excitement.

Weishaupt charged that Kant's philosophy leads to complete subjectivism and the denial of all reality independent of passing states of consciousness, a view he considered self-refuting.

The work also influenced Young Hegelians such as Bruno Bauer, Ludwig Feuerbach and Karl Marx, and also, Friedrich Nietzsche, whose philosophy has been seen as a form of "radical Kantianism" by Howard Caygill.

The late 19th-century neo-Kantians Hermann Cohen and Heinrich Rickert focused on its philosophical justification of science, Martin Heidegger and Heinz Heimsoeth on aspects of ontology, and Peter Strawson on the limits of reason within the boundaries of sensory experience.

[80] According to Physiologist Homer W. Smith, Kant's Critique of Pure Reason is important because it threw the philosophy of the nineteenth century into a state of temporary confusion.