The Demi-Virgin

Because it contained suggestive dialogue and the female cast wore revealing clothes, the production was considered highly risqué at the time.

The script alluded to a contemporary scandal involving actor Fatty Arbuckle, and one scene featured actresses stripping as part of a card game.

The story centers on the character Gloria Graham, a silent film actress who had previously been married to fellow actor Wally Deane.

After he received a late-night call on their wedding night from a former girlfriend, Gloria stormed out and went to Reno, Nevada to obtain a divorce.

[1] The first act opens with a group of actresses, including Cora Montague and Betty Wilson, filming a scene for a movie and gossiping about the failed marriage.

Betty's aunt Zeffie comes to the studio with a magazine article about how the couple has been forced to reunite to complete the movie, for which they were contracted before their break-up.

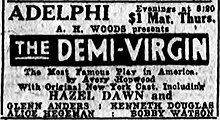

[10][11][12] For the role of Gloria Graham, producer Albert H. Woods cast Hazel Dawn, who was then starring in his production of Getting Gertie's Garter.

[14] The characters and cast from the Broadway production are listed below: Prior to writing The Demi-Virgin, Hopwood was a well-established author of bedroom comedies.

Such material had been very profitable for Woods, who commissioned originals and adapted foreign farces, and for Hopwood, who was one of the most successful authors in the genre.

Hopwood was inspired by an earlier theatrical adaptation of Les Demi-vierges, an 1894 novel by the French writer Marcel Prévost that had been dramatized in 1895, but used little from it beyond the title.

Although the play was largely written before the scandal broke, Hopwood incorporated references to Arbuckle in the first produced version of the script, through a character called "Fatty Belden".

[22][23] The witnesses against the show included John S. Sumner, executive secretary of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice,[19][24] and Edward J. McGuire, vice-chairman of the Committee of Fourteen.

[25] On November 14, McAdoo ruled that the play was obscene, describing it as "coarsely indecent, flagrantly and suggestively immoral, impure in word and action".

[19][26] Woods was placed on bail, and the case was referred to the Court of Special Sessions for a misdemeanor charge of staging an obscene exhibition.

He was accused of violating section 1140a of the New York state penal law, which prohibited involvement in "any obscene, indecent, immoral or impure drama, play, exhibition, show or entertainment".

[30] Gilchrist's effort failed when a New York state appeals court ruled on February 20, 1922 that he did not have the legal authority to revoke a theater license once it had been granted.

The costumes of its female cast members, who mostly wore revealing gowns or scanty bedroom attire, also attracted attention.

[20] The reviewer for the New York Evening Post gave the Broadway production only three sentences, claiming that there was no need for "wasting space" on the repulsive "concoction" created by Hopwood and Woods.

Woods worked around the problem by promoting the large number of people who had seen an unnamed production at his theater, with daily updates of the total.

[42][43] Woods added matinees and increased the top ticket prices; the weekly box office reached over $17,000 at the end of November.

[49][50] In 1925, Hopwood confessed to the audience at another play that he thought The Demi-Virgin was boring and that he was tired of writing faddish entertainment.

In 1923, Broadway producer Earl Carroll began his Vanities revue, featuring dozens of women in costumes considered daring at the time.

[55] The play juries proved unwilling to take the strong anti-obscenity action that Sumner and his colleagues wanted; by 1927 the system had been abandoned in favor of renewed efforts at government regulation.