The Great Train Robbery (1903 film)

The Great Train Robbery is a 1903 American silent Western action film made by Edwin S. Porter for the Edison Manufacturing Company.

It follows a gang of outlaws who hold up and rob a steam train at a station in the American West, flee across mountainous terrain, and are finally defeated by a posse of locals.

Porter supervised and photographed the film in New York and New Jersey in November 1903; the Edison studio began selling it to vaudeville houses and other venues in the following month.

Camera pans, location shooting, and moments of violent action helped give The Great Train Robbery a sense of rough-edged immediacy.

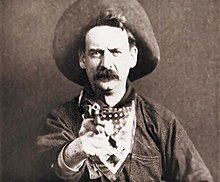

A special close-up shot, which was unconnected to the story and could either begin or end the film depending on the projectionist's whim, showed Barnes, as the outlaw leader, emptying his gun directly into the camera.

Due in part to its popular and accessible subject matter, as well as to its dynamic action and violence, The Great Train Robbery was an unprecedented commercial success.

In 1990, The Great Train Robbery was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

Two bandits break into a railroad telegraph office, where they force the operator at gunpoint to stop a train and order its engineer to fill the locomotive's tender at the station's water tank.

[3] However, other filmmakers aimed for more elaborate productions; Georges Méliès's films, such as the 1902 international success A Trip to the Moon, became acclaimed for their visual storytelling, often encompassing multiple scenes and involving careful editing and complicated special effects.

[4] Edwin S. Porter had won acclaim making cameras, film printers, and projectors; however, after his workshop was destroyed by a fire, he accepted a special commission for the Edison Manufacturing Company in 1901.

[2] However, his job also gave him the chance to view the many foreign films the Edison company were distributing and pirating,[6] and around 1901 or 1902 he discovered the more complex works being made by Méliès and the Brighton School.

[16] For the film's title and basic concept, Porter looked to Scott Marble's The Great Train Robbery, a popular stage melodrama that had premiered in Chicago in 1896 and had been revived in New York in 1902.

Their initial scheme is for a mole planted in the company to make off with the gold before it leaves Missouri by train; this plan goes awry, and only leads to an innocent man's arrest.

However, using information received at a Texas mountain saloon, the gang are still able to stop the train, blast open the car containing the gold, and bring it back to their secret hideout in a Red River canyon.

The United States Marshals Service tracks down the gang and finally defeats them in a climactic fight, with cowboys and Native Americans drawn into the fray.

[18] A Daring Daylight Burglary's story and editing appear to have supplied the overall narrative structure for The Great Train Robbery,[17][11] though in the latter film the chase is only made explicit in one shot, the twelfth.

[19] Porter's plot also profited from the booming popularity of railroad-related film attractions, such as phantom rides and standalone comic scenes set on trains.

[9] The cast included Justus D. Barnes as the leader of the outlaws, Walter Cameron as the sheriff and G. M. Anderson in three small roles (the murdered passenger, the dancing tenderfoot, and one of the robbers).

[11] Mary Jane's Mishap, a landmark dark comedy made by Brighton pioneers G. A. Smith and Laura Bayley and released months before The Great Train Robbery, is far more sophisticated in its editing and framing.

[28] The Edison Manufacturing Company announced The Great Train Robbery to exhibitors in early November 1903, calling it a "highly sensationalized Headliner".

[34] Its popularity was helped by its timely subject matter (as train robberies were still a familiar news item),[35] as well as its striking depictions of action and violence.

[38] But despite its wide success and imitators, The Great Train Robbery did not lead to a significant increase in Western films; instead, the genre continued essentially as it had before, in a scattered mix of short actualities and longer stories.

[35] Porter continued to make films for more than a decade after, usually in a similar editing style to The Great Train Robbery, with few additional technical innovations.

[31] Film historian Pamela Hutchinson highlights especially the iconic close-up scene, "a jolt of terror as disconcerting as a hand bursting from a grave": It's an especially violent act, both in real terms, and cinematic ones.