The History of King Lear

Although many critics – including Joseph Addison, August Wilhelm Schlegel, Charles Lamb, William Hazlitt, and Anna Jameson — condemned Tate's adaptation for what they saw as its cheap sentimentality, it was popular with theatregoers, and was approved by Samuel Johnson, who regarded Cordelia's death in Shakespeare's play as unbearable.

In 1838, William Charles Macready purged the text entirely of Tate, in favour of a shortened version of Shakespeare's original.

The Duke of Burgundy withdraws his suit on finding Cordelia deprived of a dowry, but the King of France gladly accepts her as his bride.

Tate's version omits the King of France, and adds a romance between Cordelia and Edgar, who never address each other in Shakespeare's original.

Cordelia explains in an aside that her motive for remaining silent when Lear demands public expressions of love is that he leave her without a dowry, so she can escape the "loathed embraces" of Burgundy.

In the words of Stanley Wells, Tate "rather asked for trouble by retaining as much of Shakespeare as he did, thereby inviting odious comparisons with verse that he wrote himself.

James Black supports this claim by stating, "The Restoration stage was often an extension of the real-life political and philosophical milieu."

[6] The theatres were closed during the Puritan Revolution, and while records from the period are incomplete, Shakespeare's Lear is only known to have been performed twice more, after the Restoration, before being replaced by Tate's version.

In the dedicatory epistle, he explains how in Shakespeare's version, he realised that he had found "a Heap of Jewels, unstrung and unpolisht; yet so dazling in their Disorder, that [he] soon perceiv'd [he] had seiz'd a Treasure", and how he found it necessary to "rectifie what was wanting in the Regularity and Probability of the Tale," a love between Edgar and Cordelia, which would make Cordelia's indifference to her father's anger more convincing in the first scene, and would justify Edgar's disguise, "making that a generous Design that was before a poor Shift to save his Life.

"[1] As Samuel Johnson wrote, more than eighty years after the appearance of Tate's version, "In the present case the public has decided.

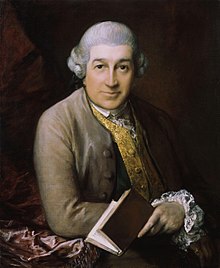

"[8] Famous Shakespearean actors such as David Garrick, John Philip Kemble, and Edmund Kean who played Lear during that period were not portraying the tragic figure who dies, broken-hearted, gazing at his daughter's body, but the Lear who regains his crown and gleefully announces to Kent: Although Shakespeare's entire text did not reappear on stage for over a century and a half, this does not mean that it was always completely replaced by Tate's version.

His performances met with enormous success, and continued to draw tears from his audiences, even without Shakespeare's final, tragic scene where Lear enters with Cordelia's body in his arms.

[10] As literary critics grew increasingly scornful of Tate, his version still remained "the starting point for performances on the English-speaking stage.

[15] Four years later, in 1838, he abandoned Tate altogether, and played Lear from a shortened and rearranged version of Shakespeare's text,[10] with which he was later to tour New York,[14] and which included the Fool and the tragic ending.

The production was successful, and marked the end of Tate's reign in the English theatre, though it was not until 1845 that Samuel Phelps restored the complete, original Shakespearean text.

[16] While Tate's version proved extremely popular on the stage, the response of literary critics has generally been negative.

An early example of approval from a critic is found in Charles Gildon's "Remarks on the Plays of Shakespeare" in 1710: The King and Cordelia ought by no means to have dy'd, and therefore Mr Tate has very justly alter'd that particular, which must disgust the Reader and Audience to have Vertue and Piety meet so unjust a Reward.

[17] The translator and author Thomas Cooke also gave Tate's version his blessing: in the introduction to his own play The Triumphs of Love and Honour (1731), he commented that Lear and Gloucester "are made sensible or their Errors, and are placed in a State of Tranquility and Ease agreeable to their Age and Condition .

And if my sensations could add anything to the general suffrage, I might relate that I was many years ago so shocked by Cordelia's death that I know not whether I ever endured to read again the last scenes of the play till I undertook to revise them as an editor.

Joseph Addison complained that the play, as rewritten by Tate, had "lost half its beauty",[20] while August Wilhelm Schlegel wrote: I must own, I cannot conceive what ideas of art and dramatic connexion those persons have who suppose that we can at pleasure tack a double conclusion to a tragedy; a melancholy one for hard-hearted spectators, and a happy one for souls of a softer mould.

[21] In a letter to the editor of The Spectator in 1828, Charles Lamb expressed his "indignation at the sickly stuff interpolated by Tate in the genuine play of King Lear" and his disgust at "these blockheads" who believed that "the daughterly Cordelia must whimper [her] love affections before [she] could hope to touch the gentle hearts in the boxes.

"[22] Some years previously, Lamb had criticised Tate's alterations as "tamperings", and had complained that for Tate and his followers, Shakespeare's treatment of Lear's story: Quoting that extract from Lamb, and calling him "a better authority" than Johnson or Schlegel "on any subject in which poetry and feelings are concerned",[24] essayist William Hazlitt also rejected the happy ending, and argued that after seeing the afflictions that Lear has endured, we feel the truth of Kent's words as Lear's heart finally breaks: The art and literature critic Anna Jameson was particularly scathing in her criticism of Tate's efforts.

replace a sceptre in that shaking hand?—a crown upon that old grey head, on which the tempest had poured in its wrath, on which the deep dread-bolted thunders and the winged lightnings had spent their fury?

While acknowledging that prior to Shakespeare's writing of King Lear, some versions of the story had ended happily, and that Tate's returning of the crown to Lear was therefore not a complete innovation, Jameson complained that on stage: they have converted the seraph-like Cordelia into a puling love heroine, and sent her off victorious at the end of the play—exit with drums and colours flying—to be married to Edgar.

[2] Sharing Johnson's view that the tragic ending was too harsh, too shocking, Bradley observed that King Lear, while frequently described as Shakespeare's greatest work, the best of his plays, was yet less popular than Hamlet, Macbeth, and Othello; that the general reader, though acknowledging its greatness, would also speak of it with a certain distaste; and that it was the least often presented on stage, as well as being the least successful there.

[28] Bradley suggested that the feeling which prompted Tate's alteration and which allowed it to replace Shakespeare on stage for over a century was a general wish that Lear and Cordelia might escape their doom.

Distinguishing between the philanthropic sense, which also wishes other tragic figures to be saved, and the dramatic sense, which does not, but which still wishes to spare Lear and Cordelia, he suggested that the emotions have already been sufficiently stirred before their deaths, and he believed that Shakespeare would have given Lear "peace and happiness by Cordelia's fireside", had he taken the subject in hand a few years later, at the time that he was writing Cymbeline and The Winter's Tale.

[29] As Tate's Lear disappeared from the stage (except when revived as a historical curiosity), and as critics were no longer faced with the difficulties of reconciling a happy ending on the stage with a tragic ending on the page, the expressions of indignation and disgust became less frequent, and Tate's version, when mentioned at all by modern critics, is usually mentioned simply as an interesting episode in the performance history of one of Shakespeare's greatest works.

Musical interludes were sung by cast members during the act breaks, accompanied by a harpsichord in the orchestra pit before the stage.

[32] The play, with its "happy ending", became known as a "King Lear for optimists" by the press, and proved one of the most popular productions by the Riverside Shakespeare Company.