Christian cross

The term cross is now detached from its original specifically Christian meaning, in modern English and many other Western languages.

[2] John Pearson, Bishop of Chester (c. 1660) wrote in his commentary on the Apostles' Creed that the Greek word stauros originally signified "a straight standing Stake, Pale, or Palisador", but that, "when other transverse or prominent parts were added in a perfect Cross, it retained still the Original Name", and he declared: "The Form then of the Cross on which our Saviour suffered was not a simple, but a compounded, Figure, according to the Custom of the Romans, by whose Procurator he was condemned to die.

[6] However, the cross symbol was already associated with Christians in the 2nd century, as is indicated in the anti-Christian arguments cited in the Octavius[7] of Minucius Felix, chapters IX and XXIX, written at the end of that century or the beginning of the next,[note 2] and by the fact that by the early 3rd century the cross had become so closely associated with Christ that Clement of Alexandria, who died between 211 and 216, could without fear of ambiguity use the phrase τὸ κυριακὸν σημεῖον (the Lord's sign) to mean the cross, when he repeated the idea, current as early as the apocryphal Epistle of Barnabas, that the number 318 (in Greek numerals, ΤΙΗ) in Genesis 14:14[9] was interpreted as a foreshadowing (a "type") of the cross (T, an upright with crossbar, standing for 300) and of Jesus (ΙΗ, the first two letters of his name ΙΗΣΟΥΣ, standing for 18).

[note 3] In his book De Corona, written in 204, Tertullian tells how it was already a tradition for Christians to trace repeatedly on their foreheads the sign of the cross.

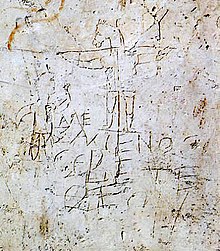

[13] The oldest extant depiction of the execution of Jesus in any medium seems to be the second-century or early third-century relief on a jasper gemstone meant for use as an amulet, which is now in the British Museum in London.

It portrays a naked bearded man whose arms are tied at the wrists by short strips to the transom of a T-shaped cross.

85–97); and the marking of a cross upon the forehead and the chest was regarded as a talisman against the powers of demons (Tertullian, "De Corona," iii.

Accordingly the Christian Fathers had to defend themselves, as early as the second century, against the charge of being worshipers of the cross, as may be learned from Tertullian, "Apologia," xii., xvii., and Minucius Felix, "Octavius," xxix.

For example, during the 16th century, theologians in the Anglican and Reformed traditions Nicholas Ridley,[36] James Calfhill,[37] and Theodore Beza,[38] rejected practices that they described as cross worship.

[39] There were more active reactions to religious items that were thought as 'relics of Papacy', as happened for example in September 1641, when Sir Robert Harley pulled down and destroyed the cross at Wigmore.

[40] Writers during the 19th century indicating a Pagan origin of the cross included Henry Dana Ward,[41] Mourant Brock,[42] and John Denham Parsons.

"[44] The study, Gods, Heroes & Kings: The Battle for Mythic Britain states: "Before the fourth century CE, the cross was not widely embraced as a sign of Christianity, symbolizing as it did the gallows of a criminal.

"[51][52] Prophet Howard W. Hunter encouraged Latter-day Saints "to look to the temple of the Lord as the great symbol of your membership.

[55] In 2014, the Chinese Communist Party, which espouses a doctrine of state atheism, began a program of removing exterior crosses from church buildings "for reasons of safety and beauty.