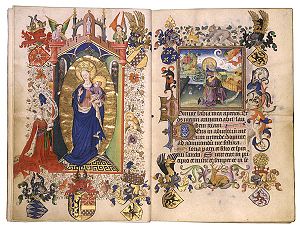

Hours of Catherine of Cleves

[1][2] This book of hours contains the usual offices, prayers and litanies in Latin, along with supplemental texts, decorated with 157 colorful and gilded illuminations.

John Plummer, Curator of Medieval Manuscripts at the Morgan Library, suggested that this Horae was commissioned for the wedding in 1430, but it required time to complete.

The earlier date is based on the picture of a coin, minted in 1434 by Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, shown in the border of M. 917, p. 240; Plummer, Plate 117.

The first page shows Catherine of Cleves kneeling before the Virgin and the Christ Child, who take a personal interest in her salvation.

[1] The borders of both pages are decorated with an heraldic display of the Arms of her eight great-great-grandfathers: Catherine of Cleves is shown kneeling before The Virgin and the Christ Child, M. 945, folio 1 verso; Plummer, Plate 1.

Hell was usually not depicted in Books of Hours, though normal in the Last Judgements in churches, because the sight was thought unwelcome to the often female patrons.

[9] Stories flow through successive pictures: a woman watches a man die, weeps, then goes on a pilgrimage; souls within Hell dine upon the Host, and are rescued by an angel.

Saint Peter is painted with the key of the Church, standing above a triskelion (a reference to the Trinity) of fresh fish as the fisher of men.

The Holy Family at dinner shows Saint Joseph wearing clogs and spooning gruel, while reclining in a barrel chair in front of a lively fire.

The early miniatures and iconography are comparable to the contemporary panel paintings of Robert Campin and Jan van Eyck, and share many close similarities.

This originality of technique and awareness of everyday life prompted Delaissé to call the Cleves Master "the ancestor of the 17th century Dutch school of painting.

A comparison of this discovered book with the Guennol Hours (M 945) revealed that not only were they by the same artist, and from the same workshop, but both Horae were incomplete and complemented each other.

[2] In connection with a 2010 exhibition entitled “Demons and Devotion: The Hours of Catherine of Cleves,” the Morgan Library disbound the two volumes to display 93 of the illuminations in their original order.

[1][7] The text is Latin in a Gothic script with black and red ink, by a single scribe; there are catchwords and rubricator's notes in other hands.

Supplementary texts were added to celebrate any personal patron, family saint, special circumstances, or a fortuitous event.

The Cleves Master was familiar with the details of humble tasks such as milking a cow, selling wine, and baking bread.

[1][5] Ingenious theological links between the subjects of the main images and the objects in the borders have been suggested by some scholars, though many of these are not generally accepted.

[2] As a whole, the Cleves Master's decorations concentrate on the great themes of late medieval theology and piety: the Trinity, Christ, the Cross, the Virgin, the Saints, death, salvation, and eternal life.

The challenge to the artists of his day was to apply their utmost skill in devising sumptuous pictures, which were fresh and delightful, but fully compliant with religious conventions and the expectations of their noble clients.

Frederick B. Adams, Jr, wrote the foreword, which incorporated comments by Harry Bober, L. M. J. Delaissé, Millard Meiss, and Erwin Panofsky.

In conjunction with a 2010 exhibition of the manuscript,[17] the Morgan Library prepared a complete digital facsimile of the miniatures and any facing text pages.

Karlfried Froehlich, Princeton Theological Seminary, makes a statement about the modern usage of books of hours: In their imaginative use of traditional iconography the artists put us in touch with a wealth of theological tradition that had developed over centuries and had marked with its symbols the meditative road into the depth dimension.