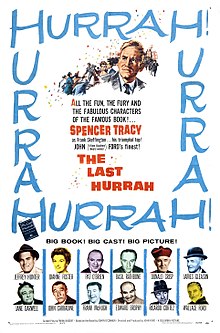

The Last Hurrah

At the beginning of the book, Skeffington is 72 and has been giving signs that he might consider retiring from public life at the end of his current term.

Developments in American public life, including the consequences of the New Deal, have so changed the face of city politics that Skeffington no longer can survive in the new age with younger voters.

Skeffington's age and background, his worship of his dead wife, his layabout son, his antagonistic relations with the members of his city's Protestant upper class, as well as his eventual defeat by a much younger candidate are all features of Curley's life and the conclusion they are one and the same seems obvious.

In a lecture at the University of New Hampshire on the book, Curley treated The Last Hurrah as a de facto biography of himself and discussed things that he believed the novel had unfairly omitted.

[7] The Last Hurrah tells the story of the end of an era of American politics characterized by the "big-city politician" as exemplified by Frank Skeffington.

The New Deal and its constituent laws implemented systems whereby the national government would "dispense money, jobs, health care, and housing."

Franklin D. Roosevelt, initiator of the New Deal, "[substituted] government social welfare programs for the corrupt ward heeler's ill-gotten private dole and power source.

Some scholars disagree with the above assertions, arguing that several city mayors have benefited from the aid that New Deal agencies gave to their constituents.

[6] The title '"The Last Hurrah" drew on a common phrase in the English lexicon to mean a swan song or, in politics, the last campaign of a politician.

[11][12] The success of the novel and Tracy's portrayal of the Curley proxy "Skeffington" in the film adaptation as rambunctious but heroic improved the public image the ex-mayor, who was no longer in office by 1956.