The Log from the Sea of Cortez

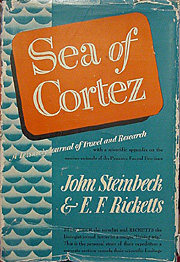

The Log from the Sea of Cortez is the narrative portion of an earlier work, Sea of Cortez: A Leisurely Journal of Travel and Research, which was published by Steinbeck and Ricketts shortly after their return from the Gulf of California, and combined the journals of the collecting expedition, reworked by Steinbeck, with Ricketts' species catalogue.

After Ricketts' death in 1948, Steinbeck dropped the species catalogue from the earlier work and republished it with a eulogy to his friend added as a foreword.

[2] Both Steinbeck and Ricketts had achieved some measure of security and recognition in their professions by 1939: Steinbeck had capitalized on his first successful novel, Tortilla Flat, with the publication of The Grapes of Wrath, and Ricketts had published Between Pacific Tides, which became the definitive handbook for the study of the intertidal fauna of the Pacific Coast of the coterminous United States.

The two men had long thought of producing a book together and, in a change of pace for both of them, they began work on a handbook of the common intertidal species of the San Francisco Bay Area.

Early in 1940, Steinbeck and Ricketts hired a Monterey Bay sardine fishing boat, the Western Flyer, with a four-man crew, and spent six weeks travelling the coast of the Gulf of California collecting biological specimens.

[5] The Western Flyer is a 75-foot (23 m) purse seiner, that was crewed by Tony Berry, the captain; "Tex" Travis, the engineer; and two able seamen, "Sparky" Enea and "Tiny" Colletto.

[6] The battles with their outboard motor, referred to pseudonymously as the "Hansen Sea-Cow", which would feature as a humorous thread throughout the journal, began immediately and continued the next day when they moved further round the coast to El Pulmo Reef:[7] Our Hansen Sea-Cow was not only a living thing but a mean, irritable, contemptible, vengeful, mischievous, hateful living thing.... [it] loved to ride on the back of a boat, trailing its propeller daintily in the water while we rowed... when attacked with a screwdriver [it] fell apart in simulated death...

It loved no one, trusted no one, it had no friends.Making for Isla Espiritu Santo they faced strong winds and, rather than attempting to land at the island, they anchored at Pescadero on the mainland.

A visit from some natives of La Paz that evening, coupled with the exhaustion of their supplies of beer, encouraged them to make for the town the next morning.

They accepted, wanting to see the interior of the peninsula, and enjoyed two days in the company of the Mexicans, eating, drinking and listening to unintelligible dirty jokes in Spanish.

Taking leave of the fleet, they made for the Estero de la Luna, a huge estuary where Ricketts and Steinbeck became lost in fog while out on a collecting expedition, after the "Sea-Cow" once again refused to run.

Three species of sea anemone they discovered were named for them by Dr. Oskar Carlgren [de; sv] at the Lund University's Department of Zoology in Sweden: Palythoa rickettsii, Isometridium rickettsi, and Phialoba steinbecki.

The book is a travelogue and biological record, but also reveals the two men's philosophies: it dwells on the place of humans in the environment,[18] the interconnection between single organisms and the larger ecosystem, and the themes of leaving and returning home.

[19] A number of ecological concerns, rare in 1940, are voiced, such as an imagined but horrific vision of the long term damage that the Japanese bottom fishing trawlers are doing to the sea bed.

A version of Ricketts' philosophical work "Essay on Non-teleological Thinking", which to some extent expressed both authors' outlooks, was included as the Easter Sunday chapter.

[18] Becoming known as the "Easter Sunday Sermon",[21] it explores the gap between the methods of science and faith and the common ground they share,[22] and it expounds on the holistic approach both men took to ecology:[23] It is advisable to look from the tide pool to the stars and then back to the tide pool again.Steinbeck enjoyed writing the book; it was a challenge to apply his novel-writing skills to a scientific subject.

He was happy that it took his writing in a new direction and would confound the attempts of the critics to pigeonhole him,[24] and, with a slightly masochistic joy he looked forward to their "rage and contempt".

[25] In that, he was proved incorrect; the reviews were mixed, but largely favorable, focusing on his affirmation of humankind's place in the wider environment, and picking up on the excitement Steinbeck and Ricketts felt for their subject.

[26] Most felt that even though there were moments when Steinbeck was at his best, the blending of philosophy, travelogue and biological recording made for an uneven read: Thus the reader will be enjoying the chase of Tethys the sea-hare when all of a sudden he will find himself becalmed in a soupy discussion of teleology.

[27] Steinbeck was right about the lack of popular appeal, however: the unusual mixture of taxonomic data and travelogue meant the book struggled to find an audience.

[30] Although Steinbeck had moved to New York City shortly after the journey and the two men had not seen as much of each other in the following years, they had corresponded by mail and had been planning a further expedition, this time northwards to the Aleutian Islands.

Although, by the time of his death in 1968, Steinbeck's reputation was at an all-time low owing to his mediocre output during the last decades of his life and his support for American involvement in Vietnam, his books have slowly regained their popularity.

[38] In particular, "About Ed Ricketts" reveals how closely he was tied to the characters in Steinbeck's novels: parts are taken almost verbatim from descriptions of "Doc" in Cannery Row.

Steinbeck bemoaned the coming of tourism:[40] Probably the airplanes will bring week-enders from Los Angeles before long, and the beautiful poor bedraggled old town will bloom with a Floridian ugliness.As of 2004 Cabo San Lucas is home to luxury hotels and the houses of American rock stars, and many of the small villages have become suburbs of the larger towns of the Gulf, but people still visit, attempting to capture something of the spirit of the leisurely journey Steinbeck and Ricketts took around the Sea of Cortez.