USS Maine (1889)

Both ships had two-gun turrets staggered en échelon, and full sailing masts were omitted due to the increased reliability of steam engines.

While some on the board supported a strict policy of commerce raiding, others argued it would be ineffective against the potential threat of enemy battleships stationed near the American coast.

(The delivery of her armored plating took three years, and a fire in the drafting room of the building yard, where Maine's working set of blueprints were stored, caused further delay.)

[15] In addition, because of the potential of a warship sustaining blast damage to herself from cross-deck and end-on fire, Maine's main-gun arrangement was obsolete by the time she entered service.

[17] A centerline longitudinal watertight bulkhead separated the engines and a double bottom covered the hull only from the foremast to the aft end of the armored citadel, a distance of 196 feet (59.7 m).

The practice of en echelon mounting had begun with Italian battleships designed in the 1870s by Benedetto Brin and followed by the British Navy with HMS Inflexible, which was laid down in 1874 but not commissioned until October 1881.

[20] This gun arrangement met the design demand for heavy end-on fire in a ship-to-ship encounter, tactics that involved ramming the enemy vessel.

[21] Her machinery, built by the N. F. Palmer Jr. & Company's Quintard Iron Works of New York,[22] was the first designed for a major ship under the direct supervision of Arctic explorer and future commodore George Wallace Melville.

[23] She had two inverted vertical triple-expansion steam engines, mounted in watertight compartments and separated by a fore-to-aft bulkhead, with a total designed output of 9,293 indicated horsepower (6,930 kW).

[17] This was a very low capacity for a ship of Maine's rating, which limited her time at sea and her ability to run at flank speed, when coal consumption increased dramatically.

Bethlehem Steel had promised the navy 300 tons per month by December 1889 and had ordered heavy castings and forging presses from the British firm of Armstrong Whitworth in 1886 to fulfil its contract.

[43] A photo of the christening shows Wilmerding striking the bow near the plimsoll line depth of 13, which caused speculation that the ship was "unlucky" from the launching.

Maine spent her active career with the North Atlantic Squadron, operating from Norfolk, Virginia, along the East Coast of the United States and the Caribbean.

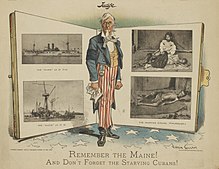

[citation needed] Its editors sent a full team of reporters and artists to Havana, including Frederic Remington,[54] and Hearst announced a reward of $50,000 ($1.83 million in 2023) "for the conviction of the criminals who sent 258 American sailors to their deaths.

The McKinley administration did not cite the explosion as a casus belli, but others were already inclined to wage war with Spain over perceived atrocities and loss of control in Cuba.

[62][4] The Spanish inquiry, conducted by Del Peral and De Salas, collected evidence from officers of naval artillery, who had examined the remains of the Maine.

Del Peral and De Salas identified the spontaneous combustion of the coal bunker, located adjacent to the munition stores in Maine, as the likely cause of the explosion.

Captain Sampson read Commander Converse a hypothetical situation of a coal-bunker fire igniting the reserve six-inch ammunition, with a resulting explosion sinking the ship.

[62] After the investigation, the newly located dead were buried in Arlington National Cemetery and the hollow, intact portion of the hull of Maine was refloated and ceremoniously scuttled at sea on 16 March 1912.

According to Wegner, Rickover interviewed naval historians at the Energy Research and Development Agency after reading an article in the Washington Star-News by John M. Taylor.

Wegner says that all relevant documents were obtained and studied, including the ship's plans and weekly reports of the unwatering of Maine in 1912 (the progress of the cofferdam) written by William Furgueson, chief engineer for the project.

Pyrites derive their name from the Greek root word pyr, meaning fire, as they can cause sparks when struck by steel or other hard surfaces.

[4] Wegner claims that technical opinion among the Geographic team was divided between its younger members, who focused on computer modeling results, and its older ones, who weighed their inspection of photos of the wreck with their own experience.

Wegner was also critical of the fact that participants in the Rickover study were not consulted until AME's analysis was essentially complete, far too late to confirm the veracity of data being used or engage in any other meaningful cooperation.

"[84] This claim has also been made in Russia by Mikhail Khazin, a Russian economist who once ran the cultural section at Komsomolskaya Pravda,[87] and in Spain by Eric Frattini, a Spanish Peruvian journalist in his book Manipulando la historia.

After lying on the bottom of Havana harbor for fourteen years these pumps were found to be still operational; they were subsequently cleaned and used by the Army Corps of Engineers to aid them in their work on the wreck.

[94] During the salvage, the remains of 66 men were found, of whom only one, Harry J. Keys (an engineering officer), was identified and returned to his home town; the rest were reburied at Arlington National Cemetery, making a total of 229 Maine crew buried there.

[97][98] On 18 October 2000, the wreck of Maine was rediscovered in about 3,770 feet (1,150 m) of water roughly 3 miles (4.8 km) northeast of Havana Harbor by Advanced Digital Communications, a Toronto-based expedition company.

Once the team began to explore the wreck with a Remotely operated underwater vehicle (ROV), they discovered that the hull had not overly oxidized, allowing them to "see all of [the ship's] structural parts.

"[99] The researchers confirmed the ship's identity both by scrutinizing the design of its doors, hatches, anchor chain, and propellers, and by identifying the telltale bulkhead that had been created when the bow was removed in 1912.