Odyssey

In antiquity, Homer's authorship was taken as true, but contemporary scholarship predominantly assumes that the Iliad and the Odyssey were composed independently, forming as part of long oral traditions.

Key themes in the epic include the ideas of nostos (νόστος; 'return', homecoming), wandering, xenia (ξενία; 'guest-friendship'), testing, and omens.

Scholars still explore on the narrative significance of certain groups in the poem, such as women and slaves, who have larger roles than in other works of ancient literature.

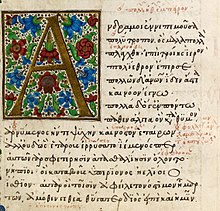

[11] In the 2nd and 3rd centuries BC, scholars affiliated with the Library of Alexandria—particularly Zenodotus and Aristarchus of Samothrace—edited the Homeric poems, wrote commentaries on them, and helped establish them as canonical texts.

[13] He mentions individual versions owned by Antimachus, Aristophanes of Byzantium, and Sosigenes; there is a record of city editions existing in Argos, Chios, Crete, Cyprus and Marseille.

[19] Alexander the Great's conquests spread Hellenistic cultural influence throughout the Eastern Mediterranean and it became read by every school child in the Greek world.

[19] During the Middle Ages, the Iliad and the Odyssey remained widely studied; as with Classical Athens, they were used as school texts within the Byzantine Empire.

[15] The first printed edition of the Odyssey, known as the editio princeps, was produced in 1488 by the Greek scholar Demetrios Chalkokondyles, who had been born in Athens and had studied in Constantinople.

[20] In 2018, the Greek Cultural Ministry revealed a clay tablet discovered near the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, containing 13 verses from the Odyssey's 14th book.

[26] Like Odysseus, Gilgamesh gets directions on how to reach the land of the dead from a divine helper: the goddess Siduri, who, like Circe, dwells by the sea at the ends of the earth, whose home is also associated with the sun.

[28] In 1914, paleontologist Othenio Abel surmised the origins of the Cyclops to be the result of ancient Greeks finding an elephant skull.

[29] Classical scholars, on the other hand, have long known that the story of the Cyclops was originally a folk tale, which existed independently of the Odyssey and which became part of it at a later date.

[32] The events in the main sequence of the Odyssey (excluding Odysseus's embedded narrative of his wanderings) have been said to take place across the Peloponnese and the Ionian Islands.

With Odysseus presumed dead, the suitors of Penelope—a crowd of 108 boisterous young men—try to persuade Penelope for her hand in marriage while partying in the king's palace.

Telemachus learns the fate of Menelaus's brother, Agamemnon, king of Mycenae and leader of the Greeks at Troy: he was murdered on his return home by his wife Clytemnestra and her lover Aegisthus.

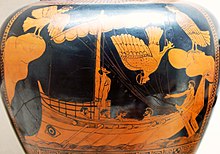

After the cannibalistic Laestrygonians destroyed all of his ships except his own, Odysseus sailed on and reached the island of Aeaea, home of witch-goddess Circe.

Odysseus takes part in the competition, and he alone is strong enough to string the bow and shoot the arrow through the dozen axe heads, making him the winner.

After the battle is won, Telemachus hangs twelve of their household slaves whom Eurycleia identifies as guilty of betraying Penelope by having sex with the suitors.

[48] Agatha Thornton examines nostos in the context of characters other than Odysseus, in order to provide an alternative for what might happen after the end of the Odyssey.

[50] Some of the other characters that Odysseus encounters are the cyclops Polyphemus, the son of Poseidon; Circe, a sorceress who turns men into animals; and the cannibalistic giants, the Laestrygonians.

[54][55] The Phaeacians demonstrate exemplary guest-friendship by feeding Odysseus, giving him a place to sleep, and granting him many gifts and a safe voyage home, which are all things a good host should do.

[59] Instead of immediately revealing his identity, he arrives disguised as a beggar and then proceeds to determine who in his house has remained loyal to him and who has helped the suitors.

This is a difficult task since it is made out of a living tree that would require being cut down, a fact that only the real Odysseus would know, thus proving his identity.

That curriculum was adopted by Western humanists,[69] meaning the text was so much a part of the cultural fabric that it became irrelevant whether an individual had read it.

[79] Emily Wilson, a professor of classical studies at the University of Pennsylvania, notes that as late as the first decade of the 21st century, almost all of the most prominent translators of Greek and Roman literature had been men.

[80] Wilson writes that this has affected the popular conception of characters and events of the Odyssey,[81] inflecting the story with connotations not present in the original text: "For instance, in the scene where Telemachus oversees the hanging of the slaves who have been sleeping with the suitors, most translations introduce derogatory language ('sluts' or 'whores') ...

[29] Edith Hall suggests that Dante's depiction of Odysseus became understood as a manifestation of Renaissance colonialism and othering, with the cyclops standing in for "accounts of monstrous races on the edge of the world", and his defeat as symbolising "the Roman domination of the western Mediterranean".

[87] Joyce claimed familiarity with the original Homeric Greek, but this has been disputed by some scholars, who cite his poor grasp of the language as evidence to the contrary.

The novella focuses on Penelope and the twelve female slaves hanged by Odysseus at the poem's ending,[90] an image which haunted Atwood.

[91] Atwood's novella comments on the original text, wherein Odysseus' successful return to Ithaca symbolises the restoration of a patriarchal system.