The Ten (Expressionists)

Although short-lived, The Ten were a seminal group, noted by art historians in connection with its members Ilya Bolotowsky, Adolph Gottlieb, and Mark Rothko.

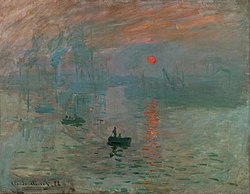

The tradition of artists jointly exhibiting work outside major venues extends at least as far back as Impressionism; this was typically done to circumvent the dominance of academic art and its associated institutions.

[5] Due to overlapping membership and their then-controversial depictions of urban scenery and the life of the working poor in New York, The Eight were closely associated with, but distinct from, The Ashcan school.

[11] Similarly, the city government had announced plans for the Municipal Art Gallery to exhibit self-organized groups of ten to fifteen artists.

[12] In Solman's account, the decision to start a new group was motivated in part by Godsoe's indiscriminate curation, which he felt diluted the quality of the shows: He began to overrun the gallery with too many painters, some of whom we consider too slight or specious for the character of the place.

Similarly although their work sometimes touched on social themes, it was not overtly political or doctrinaire—the artists sought new forms of expression which would not imitate European art or American regionalism.

As Gottlieb put it, The whole problem seemed to be how to get out of these traps—Picasso, Surrealism—and how to stay clear of American provincialism, regionalism, and social realism.The Ten held nine exhibitions of their work, including one international show and a brief art auction benefit.

The eighth and penultimate show was held at Bernard Braddon's Mercury Galleries from November 5–26, 1938, next door to the Whitney Museum of American Art.

During this period the Whitney placed a heavy emphasis on regionalism, social realism and established painters, at the expense of expressionist and abstract work.

[2] Though marketed as a provocation, the exhibit was still primarily meant to meet the practical goals of showing and selling work, while attracting attention—the group hoped to benefit from the Annual's popularity.

The exhibit's catalogue essay, co-written by Mark Rothko and Bernard Braddon, ran thus: A new academy is playing the old comedy of attempting to create something by naming it...

It is a protest against the reputed equivalence of American painting and literal painting.The Whitney Dissenters show drew more critical attention than any of The Ten's other exhibits.

By this point the founders Gottlieb and Harris had departed, and the group had served its purpose: individuals had branched out into personal styles[2] and had established relationships with galleries, and the political tensions of World War II inflamed differences among the members.

[26] As the 1930s progressed the group moved away from explicitly social themes and toward urban scenery and abstraction; Dervaux noted several titles describing nocturnes and cityscapes at the Whitney Dissenters exhibit.

She also identified Rothko's Interior as an early work which featured coloristic division of space into rectangular forms, anticipating his later color field paintings, an observation repeated by the art historian David Anfam.

Anfam observed that the grouping had identical recto and verso signatures, uniquely in Rothko's catalogue, and also had pairwise consonances and contrasts, a theme in each artist's group-of-four noted by contemporary critic Herbert Lawrence.

"[31] Writing in the left-wing review Art Front, Herbert Lawrence gave moderate praise of the group's original Montross show, albeit with reservations.