The Tower House

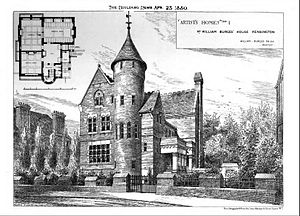

The Tower House, 29 Melbury Road, is a late-Victorian townhouse in the Holland Park district of Kensington and Chelsea, London, built by the architect and designer William Burges as his home.

The house was built by the Ashby Brothers, with interior decoration by members of Burges's long-standing team of craftsmen such as Thomas Nicholls and Henry Stacy Marks.

By 1878 the house was largely complete, although interior decoration and the designing of numerous items of furniture and metalwork continued until Burges's death in 1881.

Following a period when the house stood empty and suffered vandalism, it was purchased and restored, first by Lady Jane Turnbull, later by the actor Richard Harris and then by the musician Jimmy Page.

[8] In the following twelve years, his architecture, metalwork, jewellery, furniture and stained glass led his biographer, J. Mordaunt Crook to suggest that Burges rivaled Pugin as "the greatest art-architect of the Gothic Revival".

Although he worked to finalise earlier projects, he received no further major commissions, and the design, construction, decoration and furnishing of the Tower House occupied much of the last six years of his life.

The mosaic and marble work was contracted to Burke and Company of Regent Street, while the decorative tiles were supplied by W. B. Simpson and Sons Ltd of the Strand.

A survey undertaken in January 1965 revealed that the exterior stonework was badly decayed, dry rot had eaten through the roof and the structural floor timbers, and the attics were infested with pigeons.

"[23] In March 1965, the Historic Buildings Council obtained a preservation order on the house, enabling the purchaser of the lease, Lady Jane Turnbull, daughter of William Grey, 9th Earl of Stamford, to initiate a programme of restoration the following July.

[25] In his autobiography, the entertainer Danny La Rue recalled visiting the house with Liberace, writing, "It was a strange building and had eerie murals painted on the ceiling [...] I sensed evil".

[26] Meeting La Rue later, Harris said he had found the house haunted by the ghosts of children from an orphanage that he believed had previously occupied the site and that he had placated them by buying them toys.

[26] Harris employed the original decorators, Campbell Smith & Company Ltd., to carry out restoration,[27] using Burges's drawings from the Victoria and Albert Museum.

[31][32] "The house was exactly as he (Burges) had made and furnished it – massive, learned, glittering, amazing [...] It was strange and barbarously splendid; none more than he could be minutely intimate with the thought of old art or more saturated with a passion for colour, sheen and mystery.

Here were silver and jade, onyx and malachite, bronze and ivory, jewelled casements, rock crystal orbs, marble inland with precious metal; lustre iridescence and colour everywhere; vermillion and black, gold and emerald; everywhere device and symbolism, and a fusion of Eastern feeling with his style."

The cultural historian Caroline Dakers wrote that the Tower House was a "pledge to the spirit of Gothic in an area given over to Queen Anne".

[34] The house has an L-shaped plan, and the exterior is plain, of red brick, with Bath stone dressings and green roof slates from Cumberland.

[39] This approach, combined with Burges's architectural skills and the minimum of exterior decoration, created a building that Crook described as "simple and massive".

Massive fireplaces with elaborate overmantels were carved and installed, described by Crook as "veritable altars of art [...] some of the most amazing pieces of decoration Burges ever designed".

[49] Carved figures from the Roman de la Rose decorate the chimneypiece,[7] which Crook considered "one of the most glorious that Burges and Nicholls ever produced".

[56] The hooded chimneypiece, of Devonshire marble, contained a bronze figure above the fireplace representing the Goddess of Fame;[56] its hands and face were made of ivory, with sapphires for eyes.

[7] Its elaborate ceiling is segmented into panels by gilded and painted beams, studded with miniature convex mirrors set in to gilt stars.

[48] In this room, Burges placed two of his most personal pieces of furniture, the Red Bed, in which he died, and the Narcissus washstand, both of which originally came from Buckingham Street.

[7] The garret originally contained day and night nurseries, which the author James Stourton considers a surprising choice of arrangement for the "childless bachelor Burges".

[7] The garden at the rear of the house featured raised flowerbeds which Dakers described as being "planned according to those pleasances depicted in medieval romances; beds of scarlet tulips, bordered with stone fencing".

[11] On a mosaic terrace, around a statue of a boy holding a hawk, sculpted by Thomas Nicholls,[11][e] Burges and his guests would sit on "marble seats or on Persian rugs and embroidered cushions.

[66] The fittings were as elaborate as the furniture: the tap for one of the guest washstands was in the form of a bronze bull from whose throat water poured into a sink inlaid with silver fish.

In his major study of English domestic architecture, Das englische Haus, published some twenty years after Burges's death, Hermann Muthesius wrote of The Tower House, "Worst of all, perhaps, is the furniture.

[69] Many of the early pieces of furniture, such as the Narcissus Washstand, the Zodiac Settle and the Great Bookcase, were originally made for Burges's office at Buckingham Street and were later moved to the Tower House.

[72] John Betjeman located the Narcissus Washstand in a junk shop in Lincoln and gave it to Evelyn Waugh, a fellow enthusiast for Victorian art and architecture, who featured it in his 1957 novel, The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold.

[f][74] Several pieces purchased by Charles Handley-Read, who was instrumental in reviving interest in Burges, were acquired by The Higgins Art Gallery & Museum, Bedford.