The Troubles

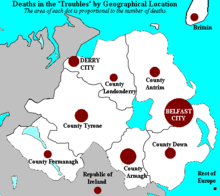

Sometimes described as an "asymmetric" or "irregular" war[26][27][28] or a "low-intensity conflict",[29][30][31] the Troubles were a political and nationalistic struggle fueled by historical events,[32] with a strong ethnic and sectarian dimension,[33] fought over the status of Northern Ireland.

[58] In response, nationalists led by Eoin MacNeill formed the Irish Volunteers in 1913, whose goal was to oppose the UVF and ensure enactment of the Third Home Rule Bill in the event of British or unionist refusal.

Two-and-a-half years after the executions of sixteen of the Rising's leaders, the separatist Sinn Féin party won the December 1918 general election in Ireland with 47% of the vote and a majority of seats, and set up the 1919 First Dáil (Irish Parliament) in Dublin.

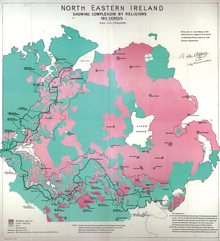

While this arrangement met the desires of unionists to remain part of the United Kingdom, nationalists largely viewed the partition of Ireland as an illegal and arbitrary division of the island against the will of the majority of its people.

[109] On 9 September, the Northern Ireland Joint Security Committee met at Stormont Castle and decided that A peace line was to be established to separate physically the Falls and the Shankill communities.

[121] Bloody Sunday was the shooting dead of thirteen unarmed men by the British Army at a proscribed anti-internment rally in Derry on 30 January 1972 (a fourteenth man died of his injuries some months later), while fifteen other civilians were wounded.

[144] British troop concentrations peaked at 1:50 of the civilian population, the highest ratio found in the history of counterinsurgency warfare, higher than that achieved during the "Malayan Emergency"/"Anti-British National Liberation War" to which the conflict is frequently compared.

Three days into the UWC strike, on 17 May 1974, two UVF teams from the Belfast and Mid-Ulster brigades[76] detonated three no-warning car bombs in Dublin's city centre during the Friday evening rush hour, resulting in 26 deaths and close to 300 injuries.

[125][148] Even as his government deployed troops in August 1969, Wilson ordered a secret study of whether the British military could withdraw from Northern Ireland, including all 45 bases, such as the submarine school in Derry.

[149] Wilson's cabinet discussed the more drastic step of complete British withdrawal from an independent Northern Ireland as early as February 1969, as one of various possibilities for the region including direct rule.

Irish Foreign Minister Garret FitzGerald discussed in a memorandum of June 1975 the possibilities of orderly withdrawal and independence, repartition of the island, or a collapse of Northern Ireland into civil war and anarchy.

FitzGerald warned Callaghan that the failure to intervene, despite Ireland's inability to do so, would "threaten democratic government in the Republic", which would jeopardise British and European security against Communist and other foreign nations.

He wrote in 2006 that "Neither then nor since has public opinion in Ireland realised how close to disaster our whole island came during the last two years of Harold Wilson's premiership";[152] in 2008, he said that the Republic "was more at risk then than at any time since our formation".

[76] On 7 August 1974, a 24 year old man from Limehill near Pomeroy, County Tyrone was shot in the back and killed by a member of the British Army (First Battalion, Royal Regiment of Wales).

[157] On 5 April 1975, Irish republican paramilitary members killed a UDA volunteer and four Protestant civilians in a gun and bomb attack at the Mountainview Tavern on the Shankill Road, Belfast.

[158][159] On 31 July 1975 at Buskhill, outside Newry, popular Irish cabaret band the Miami Showband was returning home to Dublin after a gig in Banbridge when it was ambushed by gunmen from the UVF Mid-Ulster Brigade wearing British Army uniforms at a bogus military roadside checkpoint on the main A1 road.

[161][162] The Provisional IRA had lost the hope it had felt in the early 1970s that it could force a rapid British withdrawal from Northern Ireland, and instead developed a strategy known as the "Long War", which involved a less intense but more sustained campaign of violence that could continue indefinitely.

[168] In the wake of the hunger strikes, Sinn Féin, which had become the Provisional IRA's political wing,[167][169][170] began to contest elections for the first time in both Northern Ireland (as abstentionists) and in the Republic.

[135] In March 1988, three IRA volunteers who were planning a bombing were shot dead by the SAS at a Shell petrol station on Winston Churchill Avenue in Gibraltar, the British Overseas Territory attached to the south of Spain.

[193] On 9 February 1996, less than two years after the declaration of the ceasefire, the IRA revoked it with the Docklands bombing in the Canary Wharf area of London, killing two people, injuring 39 others,[194] and causing £85 million in damage to the city's financial centre.

Lance bombardier Stephen Restorick, the last British soldier killed during the Troubles, was shot dead at a checkpoint on the Green Rd near Bessbrook on 12 February 1997 by the IRA's South Armagh sniper.

Over the years, the Provisional IRA imported arms from external sources such as sympathisers in the Republic of Ireland, Irish diaspora communities within the Anglosphere, mainland Europe, the Palestine Liberation Organization, and Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi.

[214] On the Loyalist side, the Northern Ireland Affairs Select Committee report of June 2002 stated that "in 1992 it was estimated that Scottish support for the UDA and UVF might amount to £100,000 a year.

The fact that Northern Ireland remains predominantly a cash economy also encourages a local focus, as it facilitates money laundering and makes it difficult for the law enforcement agencies to trace transactions.

[239] During the 1970s, the Glenanne gang – a secret alliance of loyalist militants, British soldiers, and RUC officers – carried out a string of gun and bomb attacks against nationalists in an area of Northern Ireland known as the "murder triangle".

[248][253] A Police Ombudsman report from 2007 revealed that UVF members had been allowed to commit a string of terrorist offences, including murder, while working as informers for RUC Special Branch.

[281] The legacy of the Troubles has been viewed by some, including researcher Rupert Taylor, as still persistent in Northern Ireland more than two decades after the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, as inequality and division between Catholics and Protestants continue.

According to social worker and author Sarah Nelson, this problem of homelessness and disorientation contributed to the breakdown of the normal fabric of society, allowing for paramilitaries to exert a strong influence in certain districts.

[283] According to one historian of the conflict, the stress of the Troubles engendered a breakdown in the previously strict sexual morality of Northern Ireland, resulting in a "confused hedonism" in respect of personal life.

[286] The Department of Health has looked at a report written in 2007 by Mike Tomlinson of Queen's University, which asserted that the legacy of the Troubles has played a substantial role in the current rate of suicide in Northern Ireland.