The West as America

Television crews from Austria, Italy, and the United States Information Agency vied to videotape the show before its 164 paintings, drawings, photographs, sculptures, and prints, along with the 55 text panels accompanying the artworks, were taken down.

[4] Republican members of the Senate Appropriations Committee were angered by what they termed the show's "political agenda" and threatened to cut funds to the Smithsonian Institution.

[4] Several key factors, including a prominent venue, skillful promotion, widespread publicity, an elaborate catalog, and the importance of the artworks themselves, all contributed to the impact of the exhibition.

[3] The history of the United States' westward expansion is viewed by some as a vital component in interpreting the structure of American culture and the modern national identity.

It was curated by William H. Truettner and a team of seven scholars of American art, including Nancy K. Anderson, Patricia Hills, Elizabeth Johns, Joni Louise Kinsey, Howard R. Lamar, Alex Nemerov, and Julie Schimmel.

"[4] In an effort to create a show that would effectively question past interpretations of familiar works by these artists, the curator divided the artworks into six thematic categories that were accompanied by 55 written text labels.

The exhibition began with historical paintings that introduced the concept of national expansion and included representations of colonial and pre-colonial events such as white male Europeans encountering the unknown North American continent for the first time.

William S. Jewett's The Promised Land – The Grayson Family (1850), portrays a prosperous-looking man with his wife and son, all gazing west, posed against a golden landscape.

The text labels called it "more rhetorical than factual", an image that "ignores the controversy that attended national expansion by equating the westward trek of the Grayson Family with white people's belief in the idea of progress.

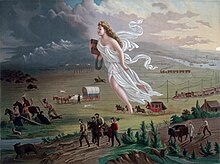

"[9] John Gast's American Progress (1872) depicts the ideal of "Manifest Destiny", a notion popular in the 1840s and 1850s which expounded that the United States was impelled by providence to expand its territory.

[10] Called the "Spirit of the Frontier", the scene was widely distributed as an engraving that portrayed settlers moving west, guided and protected by a goddess-like national personification known as Columbia, aided by technology (such as railways and telegraphs), and driving Native Americans and bison into obscurity.

These images communicated that opportunities on the frontier awaited everyone and perpetuated the myth that the settling of the west was peaceful, when in reality it was bitterly contested every step of the way.

[4] Truettner's original label read, "This predominance of negative and violent views was a manifestation of Indian hatred, a largely manufactured, calculated reversal of the basic facts of white encroachment and deceit."

Truettner explained in an oral interview with Andrew Gulliford that he made changes to the text because he "wanted to catch visitors, not alienate them" and because he believes "in communicating with the larger museum audience."

This assessment gave way gradually to a far more violent view that stressed hostile savagery…apparent in contrasting works…[7] Charles Deas' The Death Struggle (1845) depicts a white man and a Native American locked in mortal combat and tumbling over a cliff.

[1] Truettner concludes, "The myth in this case denies the Indian problem by solving it two ways: those who could not accept Anglo-Saxon standards of progress were doomed to extinction.

[4] Works in this section included Oscar E. Berninghaus' A Showery Day, Grand Canyon (1915), Andrew Joseph Russell's Temporary and Permanent Bridges and Citadel Rock, Green River (1868), Thomas Moran's The Chasm of the Colorado (1873–1874), and Albert Bierstadt's Donner Lake from the Summit (1873), as well as commercial landscapes and advertising images by unidentified artists, entitled Splendid (1935) and Desert Bloom (1938).

Roger B. Stein writes, "The much disputed critical reading of Irving Couse's The Captive (1892), an image of an old chief with his young white "victim," raised explicit questions about the intersection of gender and race and the function of the gaze in constructing meaning in this troubled emotional and cultural territory in a way that shocked viewers because it had not been prepared for earlier."

Stein adds: The curatorial experiment failed not because what the textblock said was untrue (though it was partial, inadequate and rhetorically over-insistent) but because the significant verbal comment on gender had been withheld until the last room of the exhibit.

"[4] According to The Western Historical Quarterly writer B. Byron Price, the traditions and myths at the core of western art, in addition to the expense of exhibit installations and practical constraints such as time, space, format, patronage, and availability of collections, contribute to the resistance of museums to attempt shows of historical revision and why conventional monolithic views of the West as a romantic and triumphant adventure remain the mode in many art exhibits today.

[3] Roger B. Stein, in an article for The Public Historian entitled "Visualizing Conflict in 'The West As America'", took the view that the show effectively communicated its revisionist claims by insisting upon a non-literal way of reading images through its use of textblocks.

"[11] Other critics accused the NMAA curator of "redefining western artists as apologists for Manifest Destiny who were culturally blind to the displacement of indigenous people and ignored the environmental degradation that accompanied the settling of the West.

[4] Revisionist themes appear more often in the story lines of high-profile temporary and traveling shows like The American Cowboy, organized by the Library of Congress in 1983, The Myth of the West, a 1990 show offering from the Henry Gallery of the University of Washington, and Discovered Lands, Invented Pasts, a cooperative effort of the Gilcrease Museum, the Yale University Art Gallery, and the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library in 1992.

[3] Andrew Gulliford writes, "Few Americans were prepared for the blunt and incisive exhibit labels, which sought to reshape the opinions of museum visitors and to jar them out of their traditional assumptions about western art as authentic.

According to reviewers in the media, for those who understood the war as a triumph of American values, the exhibition's critical stance toward western expansion seemed like a full-blown attack on the nation's founding principles.

"[4] In a book for comments by visitors, historian and former Librarian of Congress Daniel Boorstin wrote that the exhibition was "...a perverse, historically inaccurate, destructive exhibit… and no credit to the Smithsonian.

"[14] According to the Senators, the problem with The West As America as well as with other curatorial controversies produced by the Smithsonian and the National Endowment for the Arts such as the Mapplethorpe and Andre Serrano photographs, was that it "breeds division within our country.

The use of words and phrases such as "race", "class", and "sexual stereotype" in the exhibit's text labels allowed critics of so-called "multicultural education" to condemn the show as "politically correct".

"[4] In a hearing of the Senate Appropriations Committee on May 15, 1991, Stevens criticized the Smithsonian for demonstrating a "leftist slant" and accused The West As America of having a "political agenda", citing the exhibition's 55 text cards accompanying the artworks as a direct rejection of the traditional view of United States history as a triumphant, inevitable march westward.

"[5] Stevens called the show "perverted" but later conceded to Newsweek magazine he had not actually seen the exhibit on the West but had "merely been alerted by the comment posted by Daniel Boorstin in the museum's guestbook.