The World Without Us

Weisman concludes that residential neighborhoods would become forests within 500 years, and that radioactive waste, bronze statues, plastics and Mount Rushmore would be among the longest-lasting evidence of human presence on Earth.

Indeed, an extremely popular 1949 novel, Earth Abides, portrayed the breakdown of urban systems and structures after a pandemic, through the eyes of a survivor, who muses at the end of the first chapter: "What would happen to the world and its creatures without man?

Interviews with academics quoted in the book include biologist E. O. Wilson on the Korean Demilitarized Zone,[10] archaeologist William Rathje on plastics in garbage,[11] forest botanist Oliver Rackham on vegetative cover across Britain,[12] anthropologist Arthur Demarest on the crash of Mayan civilization,[13] paleobiologist Douglas Erwin on evolution,[14] and philosopher Nick Bostrom on Transhumanism.

[18] He tries to conceive how life may evolve by describing the past evolution of pre-historic plants and animals, but notes Douglas Erwin's warning that "we can't predict what the world will be 5 million years later by looking at the survivors".

He profiles soil samples from the past 200 years and extrapolates concentrations of heavy metals and foreign substances into a future without industrial inputs.

With material from previous articles, Weisman uses the fate of the Mayan civilization to illustrate the possibility of an entrenched society vanishing and how the natural environment quickly conceals evidence.

From interviews with members of the Wildlife Conservation Society who developed the Mannahatta Project[24] and with the New York Botanical Gardens[25] Weisman predicts that native vegetation would return, spreading from parks and out-surviving invasive species.

"[30] He responded to criticism of this saying "I knew in advance that I would touch some people's sensitive spots by bringing up the population issue, but I did so because it's been missing too long from the discussion of how we must deal with the situation our economic and demographic growth have driven us too (sic)".

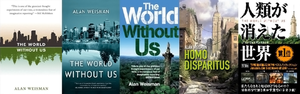

It has been translated and published in Denmark by Borgen as Verden uden os, France by Groupe Flammarion as Homo disparitus,[31] in Germany by Piper as Die Welt ohne uns,[32] in Portugal by Estrela Polar as O Mundo Sem Nós,[33] in Italy by Einaudi as Il mondo senza di noi,[34] in Poland by CKA as Świat bez nas,[35] and in Japan by Hayakawa Publishing as Jinrui ga kieta sekai (人類が消えた世界; "A World where the Human Race has Disappeared").

[36] Pete Garceau designed the cover art for the American release, which one critic said was "a thick layer of sugar-coated sweetness in an effort to not alarm potential readers.

[42] Meanwhile, the book debuted on the New York Times Best Seller list for non-fiction hardcovers at #10 on July 29[43] and spent nine weeks in the top ten,[44] peaking at #6 on August 12 and September 9.

[57] In The New York Times Book Review Jennifer Schuessler said Weisman has a "flirtation with religious language, his occasionally portentous impassivity giving way to the familiar rhetoric of eco-hellfire".

[56] The Plain Dealer book editor Karen Long said Weisman "uses the precise, unhurried language of a good science writer and shows a knack for unearthing unexpected sources and provocative facts".

[60] Robert Braile in The Boston Globe wrote that it has "no real context ... no rationale for probing this fantasy other than [Weisman's] unsubstantiated premise that people find it fascinating".

[57] On the other hand, Alanna Mitchell in the Globe and Mail review found relevance in the context of society's passiveness to resource depletion combined with an anthropomorphic vanity.

[61] Environmentalist Alex Steffen found the book presents nothing new, but that using the sudden and clean disappearance of humans provides a unique framework, although extremely unlikely and insensitive.

Science fiction writers such as H. G. Wells (The War of the Worlds, 1898) and John Wyndham (The Day of the Triffids, 1951) had earlier touched upon the possible fate of cities and other man-made structures after the sudden removal of their creators.

Similar parallels in the decay of civilization are detailed in 1949 post-apocalyptic science fiction novel by Berkeley English professor George R. Stewart, Earth Abides.

[71] Josie Appleton of Spiked related the book to "today's romanticisation of nature" in that it linked "the decadence and detachment of a modern consumerist society" with an ignorance of the efforts required to produce products so easily disposed.

[17] Weisman's science journalism style uses interviews with academic and professional authorities to substantiate conclusions, while maintaining the "cool and dispassionate [tone] ... of a scientific observer rather than an activist".

"[71] Richard Fortey compares the book to the works of Jared Diamond, Tim Flannery and E. O. Wilson, and writes that The World Without Us "narrowly avoids engendering the gloom-and-doom ennui that tends to engulf the poor reader after reading a catalogue of human rapacity".

[72] Mark Lynas in the New Statesman noted that "whereas most environmental books sag under the weight of their accumulated bad news, The World Without Us seems refreshingly positive".

[75] The 2017 video game NieR: Automata, which considers the Earth devoid of humanity for several hundreds of years, draws heavy inspiration from The World Without Us's depictions of cities and former civilisation habitats in its level design.