Theatre of Dionysus

The theatre reached its fullest extent in the fourth century BC under the epistates of Lycurgus when it would have had a capacity of up to 25,000,[3] and was in continuous use down to the Roman period.

[11] At the temenos the earliest structures were the Older Temple, which housed the xoanon of Dionysos, a retaining wall to the north[12] and slightly further up the hill a circular[13] terrace that would have been the first orchestra of the theatre.

The dramatic action of the plays does point to the presence of a skene or background scenery of some description, the strongest evidence of which is from the Oresteia that requires a number of entrances and exits from a palace door.

[17] Whether this was a temporary or permanent wooden structure or simply a tent remains unclear since there is no physical evidence for a skene building until the Periclean phase.

However, Oliver Taplin questions the seemingly inconsistent use of the device for the dramatic passages claimed for it, and doubts whether the mechanism existed in Aeschylus' lifetime.

Inscribed blocks, displaced but preserved in the retaining walls, with fifth-century BC epigraphy on them might indicate dedicated or numbered stone seats.

From these we can deduce that stock sets may have been in use to meet the requirements of the plays such that the Periclean reconstruction included post-holes built into the terrace wall to provide sockets for movable scenery.

[35] Lycurgus was a leading figure in Athenian politics in the mid- to late-fourth century prior to the Macedonian supremacy, and controller of the state's finances.

[37] Since the Choragic Monument of Thrasyllos of 320/319 BC required the rock face to be cut back such that it is likely that the epitheatron beyond the peripatos would have reached that point by then.

A coin of the Hadrianic period[38] crudely suggests a division of the theatre into two sections, but only one diazoma, or horizontal aisle, and not two if the epitheatron went past the peripatos.

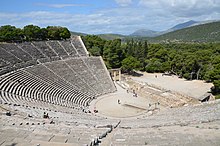

[39] The auditorium was divided by twelve narrow stairways into thirteen wedge-shaped blocks, kerkides, two additional staircases ran inside the two southern supporting walls.

Originally sixty-seven in number, the surviving ones each bear the name of the priest or official who occupied it, the inscriptions are all later than the fourth century, albeit with signs of erasure, and from the Hellenistic or Roman periods.

On this second storey and set back from the logeion is conjectured to be the episkenion whose facade was punctured with several thyromata or apertures where the pinakes or painted scenery would have been displayed.

Vitruvius places three doors on the scaenae frons with a periaktos are the extreme ends which could be deployed to indicate that the actor coming stage-left or -right was at a given location in the dramatic context.

[56] The skene foundation was underpinned with limestone blocks in this period, the orchestra was reduced in size and refloored in varicoloured marble with a rhombus pattern in the centre.

After the late 5th century AD the theatre was abandoned: its orchestra became an enclosed courtyard for a Christian basilica (aithrion) which was built into the eastern parados, while its cavea served as a stone quarry.

[63] While ancient drama undoubtedly excited passion in contemporary spectators, there remains the question of to what degree they valued or appreciated the work before them.

While the plays of the time are addressed to the adult male citizen class of the city, it is apparent that metics, foreigners and slaves were also in attendance;[66] the cost of tickets was underwritten by the Theoric Fund.

The ERATO project in 2003–2006,[71] Gade and Angelakis in 2006,[72] and Psarras et al. in 2013[73] used omnidirectional source-receivers to make measured maps of strength, reverberation and clarity.

Their findings were that the speech clarity was best in the Odeon of Herodes Atticus and that there is a greater degree of reverberation at Epidaurus due to reflection from the opposing seats.