Thebes, Greece

Archaeological excavations in and around Thebes have revealed a Mycenaean settlement and clay tablets written in the Linear B script, indicating the importance of the site in the Bronze Age.

Macedonia would rise in power at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC, bringing decisive victory to Philip II over an alliance of Thebes and Athens.

Thebes was a major force in Greek history prior to its destruction by Alexander the Great in 335 BC, and was the dominant city-state at the time of the Macedonian conquest of Greece.

[3] Archaeological excavations in and around Thebes have revealed cist graves dated to Mycenaean times containing weapons, ivory, and tablets written in Linear B.

Deger-Jalkotzy claimed that the statue base from Kom el-Hetan in Amenhotep III's kingdom (LHIIIA:1) mentions a name similar to Thebes, spelled out quasi-syllabically in hieroglyphs as d-q-e-i-s, and considered to be one of four tj-n3-jj (Danaan?)

In the late LHIIIB, according to Palaima,[6] *Tʰēgʷai was able to pull resources from Lamos near Mount Helicon, and from Karystos and Amarynthos on the Greek side of the isle of Euboia.

Though a contingent of 400 was sent to Thermopylae and remained there with Leonidas before being defeated alongside the Spartans,[7] the governing aristocracy soon after joined King Xerxes I of Persia with great readiness and fought zealously on his behalf at the Battle of Plataea in 479 BC.

[citation needed] The victorious Greeks subsequently punished Thebes by depriving it of the presidency of the Boeotian League and an attempt by the Spartans to expel it from the Delphic amphictyony was only frustrated by the intercession of Athens.

The great citadel of Cadmea served this purpose well by holding out as a base of resistance when the Athenians overran and occupied the rest of the country (457–447 BC).

In 424 BC, at the head of the Boeotian levy, they inflicted a severe defeat on an invading force of Athenians at the Battle of Delium, and for the first time displayed the effects of that firm military organization that eventually raised them to predominant power in Greece.

After the downfall of Athens at the end of the Peloponnesian War, the Thebans, having learned that Sparta intended to protect the states that Thebes desired to annex, broke off the alliance.

The result of the war was especially disastrous to Thebes, as the general settlement of 387 BC stipulated the complete autonomy of all Greek towns and so withdrew the other Boeotians from its political control.

In the consequent wars with Sparta, the Theban army, trained and led by Epaminondas and Pelopidas, proved itself formidable (see also: Sacred Band of Thebes).

They carried their arms into Peloponnesus and at the head of a large coalition, permanently crippled the power of Sparta, in part by freeing many helot slaves, the basis of the Spartan economy.

[10] Plutarch, however, writes that Alexander grieved after his excess, granting them any request of favors, and advising they pay attention to the invasion of Asia, and that if he failed, Thebes might once again become the ruling city-state.

[14] In addition to currying favor with the Athenians and many of the Peloponnesian states, Cassander's restoration of Thebes provided him with loyal allies in the Theban exiles who returned to resettle the site.

[14] Cassander's plan for rebuilding Thebes called for the various Greek city-states to provide skilled labor and manpower, and ultimately it proved successful.

This last siege was difficult and Demetrius was wounded, but finally he managed to break down the walls and to take the city once more, treating it mildly despite its fierce resistance.

[15] Though severely plundered by the Normans in 1146, Thebes quickly recovered its prosperity and continued to grow rapidly until its conquest by the Latins of the Fourth Crusade in 1205.

[16] The record of the earliest days of Thebes was preserved among the Greeks in an abundant mass of legends that rival the myths of Troy in their wide ramification and the influence that they exerted on the literature of the classical age.

Five main cycles of story may be distinguished: The Greeks attributed the foundation of Thebes to Cadmus, a Phoenician king from Tyre (now in Lebanon) and the brother of Queen Europa.

Cadmus was famous for teaching the Phoenician alphabet and building the Acropolis, which was named the Cadmeia in his honor and was an intellectual, spiritual, and cultural center.

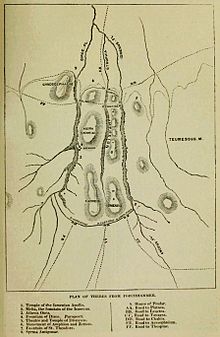

Thebes is situated in a plain, between Lake Yliki (ancient Hylica) to the north, and the Cithaeron mountains, which divide Boeotia from Attica, to the south.