Themes in Maya Angelou's autobiographies

Her original goal was to write about the lives of Black women in America, but it evolved in her later volumes to document the ups and downs of her own personal and professional life.

Scholar Yolanda M. Manora called the travel motif in Angelou's autobiographies, beginning in Caged Bird, "a central metaphor for a psychic mobility".

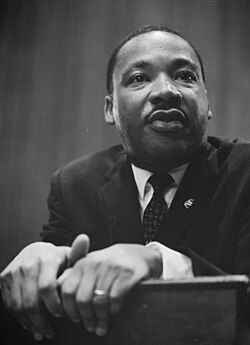

[2] Angelou's autobiographies "stretch time and place",[3] from Arkansas to Africa and back to the US, and span almost forty years, beginning from the start of World War II to the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. Before writing I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings at the age of forty, Maya Angelou had a long and varied career, holding jobs such as composer, singer, actor, civil rights worker, journalist, and educator.

[4] In the late 1950s, she joined the Harlem Writers Guild, where she met a number of important African-American authors, including her friend and mentor James Baldwin.

[6][7] Angelou was deeply depressed in the months following King's assassination, so to help lift her spirits, Baldwin brought her to a dinner party at the home of cartoonist Jules Feiffer and his wife Judy in late 1968.

One of her goals, beginning with Caged Bird, was to incorporate "organic unity" into them, and the events she described were episodic, crafted like a series of short stories, and were placed to emphasize the themes of her books.

She wrote on yellow legal pads while lying on the bed, with a bottle of sherry, a deck of cards to play solitaire, Roget's Thesaurus, and the Bible, and left by the early afternoon.

[15] Angelou went through this process to give herself time to turn the events of her life into art,[15] and to "enchant" herself; as she said in a 1989 interview with the BBC, to "relive the agony, the anguish, the Sturm und Drang".

[21] Scholar Lynn Z. Bloom asserted that Angelou's autobiographies and lectures, which she called "ranging in tone from warmly humorous to bitterly satiric",[22] have gained a respectful and enthusiastic response from the general public and critics.

[25] Hagen also argued that Angelou promotes the importance of hard work, a common theme in slave narratives, throughout all her autobiographies, in order to break stereotypes of laziness associated with African-Americans.

[26] For instance, Angelou's description of the strong and cohesive Black community of Stamps demonstrates how African Americans have subverted repressive institutions to withstand racism.

[28] Critic Pierre A. Walker placed Angelou's autobiographies in the African-American literature tradition of political protest written in the years following the American Civil Rights Movement.

[33] It begins with a prologue describing the confusion and disillusionment of the African-American community during that time, which matched the alienated and fragmented nature of the main character's life.

[40] Scholar Lyman B. Hagen agreed and pointed out that Angelou had to re-examine her lingering prejudices when faced with a broader world full of different kinds of white people.

McPherson argued that even Angelou's decision to leave show business was political,[52] and regarded this book as "a social and cultural history of Black Americans"[53] during the late 1950s and early 1960s.

[54] She became more attracted to the causes of Black militants, both in the U.S. and in Africa, to the point of entering into a relationship with South African freedom fighter Vusumzi Make, and became more committed to activism.

[59] Her experiences as an expatriate helped her come to terms with her personal and historical past, and by the end of the book she is ready to return to America with a deeper understanding of both the African and American parts of her character.

In Traveling Shoes, Angelou is able to recognize similarities between African and African-American culture; as Lupton put it, the "blue songs, shouts, and gospels" she has grown up with in America "echo the rhythms of West Africa".

These and other experiences in Ghana demonstrated Angelou's maturity, as a mother able to let go of her adult son, as a woman no longer dependent upon a man, and as an American able to "perceive the roots of her identity"[63] and how they affected her personality.

[67] Angelou learned about herself and about racism throughout Traveling Shoes, even during her brief tour of Venice and Berlin for the revival of The Blacks, the play by Jean Genet that Angelou had originally performed in 1961;[68] reuniting with the play's original cast, she revived her passion for African-American culture and values, "putting them into perspective" as she compared them with Germany's history of racial prejudice and military aggression.

[69] The verbal violence of the folk tales shared during her luncheon with her German hosts and Israeli friend was as significant to Angelou as physical violence, to the point that she became ill. Angelou's experience with fascism in Italy, her performances with 'The Blacks cast, and the reminders of the holocaust in Germany, "help[ed] shape and broaden her constantly changing vision" [70] regarding racial prejudice, clarified her perceptions of African Americans, and "contribute to her reclaiming herself and her evolution as a citizen of the world".

Angelou also presents herself as a role model for African-American women more broadly by reconstructing the Black woman's image through themes of individual strength and the ability to overcome.

Flowers (who helps Angelou find her voice again after her rape), collaborated to "form a triad which serves as the critical matrix in which the child is nurtured and sustained during her journey through Southern Black girlhood".

[76][note 2] Angelou's original goal was to write about the lives of Black women in America, but her voluminous work documents the ups and downs of her own life as well.

[21] In her third autobiography, Singin' and Swingin' and Gettin' Merry Like Christmas, Angelou successfully demonstrates the integrity of the African-American character as she began to experience more positive interactions with whites.

[12] Lupton believed that Angelou's plot construction and character development were influenced by the mother/child motif found in the work of Harlem Renaissance poet Jessie Fauset.

[87] Koyana stated that it was not until Angelou was able to take advantage of opportunities, such as her role in Porgy and Bess, when she was able to fully support herself and her son Guy, and the quality of her life and her contribution to society improved.

[90] Black women autobiographers like Angelou have debunked stereotypes surrounding African-American mothers, such as "breeder and matriarch", and have presented them as having more creative and satisfying roles.

[93] Koyana recognized that Angelou depicted women and "womanist theories" [87] in an era of cultural transition, and that her books described one Black woman's attempts to create and maintain a healthy self-esteem.

[100] As a Black American, her travels around the world put her in contact with many nationalities and classes, expanded her experiences beyond her familiar circle of community and family, and complicated her understandings of race relations.