Themistocles

Due to his subterfuge, the Allies successfully lured the Persian fleet into the Straits of Salamis, and the decisive Greek victory there was the turning point of the war.

[17] The Athenian people thus overthrew Isagoras, repelled a Spartan attack under Cleomenes, and invited Cleisthenes to return to Athens and put his plan into action.

Touring the taverns, the markets, the docks, canvassing where no politician had thought to canvas before, making sure never to forget a single voter's name, Themistocles had set his eyes on a radical new constituency...[20]However, he took care to ensure that he did not alienate the nobility of Athens.

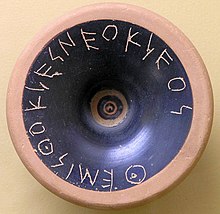

[24] This was 'ostracism'—each Athenian citizen was required to write on a shard of pottery (ostrakon) the name of a politician that they wished to see exiled for a period of ten years.

[24] Themistocles, with his power-base firmly established among the poor, moved naturally to fill the vacuum left by Miltiades' death, and in that decade became the most influential politician in Athens.

[25] Plutarch suggests that the rivalry between the two had begun when they competed over the love of a boy: "... they were rivals for the affection of the beautiful Stesilaus of Ceos, and were passionate beyond all moderation.

[37] A force of 10,000 hoplites was dispatched under the command of the Spartan polemarch Euenetus and Themistocles to the Vale of Tempe, which they believed the Persian army would have to pass through.

[41] As Holland has it: What precise heights of oratory he attained, what stirring and memorable phrases he pronounced, we have no way of knowing...only by the effect it had on the assembly can we gauge what surely must have been its electric and vivifying quality—for Themistocles's audacious proposals, when put to the vote, were ratified.

The Athenian people, facing the gravest moment of peril in their history, committed themselves once and for all to the alien element of the sea, and put their faith in a man whose ambitions many had long profoundly dreaded.

When the Persian fleet finally arrived at Artemisium after a significant delay, Eurybiades, who both Herodotus and Plutarch suggest was not the most inspiring commander, wished to sail away without fighting.

"[54] Themistocles claimed that the Allied commanders were infighting, that the Peloponnesians were planning to evacuate that very night, and that to gain victory all the Persians needed to do was to block the straits.

[62] In the ensuing battle, the cramped conditions in the Straits hindered the much larger Persian navy, which became disarrayed, and the Allies took advantage to win a famous victory.

"[5] The Allied victory at Salamis ended the immediate threat to Greece, and Xerxes now returned to Asia with part of the army, leaving his general Mardonius to attempt to complete the conquest.

[72][73] Furthermore, Plutarch reports that at the next Olympic Games: [When] Themistocles entered the stadium, the audience neglected the contestants all day long to gaze on him, and pointed him out with admiring applause to visiting strangers, so that he too was delighted, and confessed to his friends that he was now reaping in full measure the harvest of his toils in behalf of Hellas.

[74][75]However, as happened to many prominent individuals in the Athenian democracy, Themistocles's fellow citizens grew jealous of his success, and possibly tired of his boasting.

[78] In the summer of that year, after receiving an Athenian ultimatum, the Peloponnesians finally agreed to assemble an army and march to confront Mardonius, who had reoccupied Athens in June.

[84] By delaying in this manner, Themistocles gave the Athenians enough time to fortify the city, and thus ward off any Spartan attack aimed at preventing the re-fortification of Athens.

[86] Themistocles introduced tax breaks for merchants and artisans, to attract both people and trade to the city to make Athens a great mercantile centre.

[87] Plutarch reports that Themistocles also secretly proposed to destroy the beached ships of the other Allied navies to ensure complete naval dominance—but was overruled by Aristides and the council of Athens.

[88] It seems clear that, towards the end of the decade, Themistocles had begun to accrue enemies, and had become arrogant; moreover his fellow citizens had become jealous of his prestige and power.

[82] In Athens itself, he lost favour by building a sanctuary of Artemis, with the epithet Aristoboulẽ ("of good counsel") near his home, a blatant reference to his own role in delivering Greece from the Persian invasion.

[76][90] In itself, this did not mean that Themistocles had done anything wrong; ostracism, in the words of Plutarch, "was not a penalty, but a way of pacifying and alleviating that jealousy which delights to humble the eminent, breathing out its malice into this disfranchisement."

[94][95] Desperate to avoid the legal authorities, Themistocles, who had been traveling under an assumed identity, revealed himself to the captain and said that if he did not reach safety he would tell the Athenians that he'd bribed the ship to take him.

[104] Themistocles was one of the several Greek aristocrats who took refuge in the Achaemenid Empire following reversals at home, other famous ones being Hippias, Demaratos, Gongylos or later Alcibiades.

[4][101] However, perhaps inevitably, there were also rumours surrounding his death, saying that unwilling to follow the Great King's order to make war on Athens, he committed suicide by taking poison, or drinking bull's blood.

[4][101][102][118] Plutarch provides the most evocative version of this story: But when Egypt revolted with Athenian aid...and Cimon's mastery of the sea forced the King to resist the efforts of the Hellenes and to hinder their hostile growth...messages came down to Themistocles saying that the King commanded him to make good his promises by applying himself to the Hellenic problem; then, neither embittered by anything like anger against his former fellow-citizens, nor lifted up by the great honor and power he was to have in the war, but possibly thinking his task not even approachable, both because Hellas had other great generals at the time, and especially because Cimon was so marvelously successful in his campaigns; yet most of all out of regard for the reputation of his own achievements and the trophies of those early days; having decided that his best course was to put a fitting end to his life, he made a sacrifice to the gods, then called his friends together, gave them a farewell clasp of his hand, and, as the current story goes, drank bull's blood, or as some say, took a quick poison, and so died in Magnesia, in the sixty-fifth year of his life...They say that the King, on learning the cause and the manner of his death, admired the man yet more, and continued to treat his friends and kindred with kindness.

[123][124][125][126] Archeptolis also minted his own silver coinage as he ruled Magnesia, and it is probable that part of his revenues continued to be handed over to the Achaemenids in exchange for the maintenance of their territorial grant.

[128] Themistocles also had several other daughters, named Nicomache, Asia, Italia, Sybaris, and probably Hellas, who married the Greek exile in Persia Gongylos and still had a fief in Persian Anatolia in 400/399 BC as his widow.

[120] One of the descendants of Cleophantus still issued a decree in Lampsacus around 200 BC mentioning a feast for his own father, also named Themistocles, who had greatly benefited the city.

[25] Yet, set against these negative traits, was an apparently natural brilliance and talent for leadership:[20] Both Herodotus and Plato record variations of an anecdote in which Themistocles responded with subtle sarcasm to an undistinguished man who complained that the great politician owed his fame merely to the fact that he came from Athens.