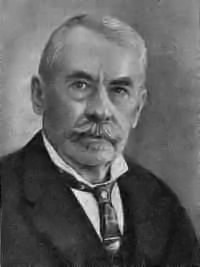

Theodor Fritsch

He is not to be confused with his son, also named Theodor Fritsch (1895–1946) and also a bookseller, who was a member of the paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party, the Sturmabteilung.

Nietzsche sent Fritsch a letter in which he thanked him to be permitted "to cast a glance at the muddle of principles that lie at the heart of this strange movement", but requested not to be sent again such writings, for he was afraid that he might lose his patience.

In 1902 Fritsch founded a Leipzig publishing house, Hammer-Verlag, whose flagship publication was The Hammer: Pages for German Sense (1902–1940).

The firm issued German translations of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion and The International Jew (collected writings of Henry Ford from The Dearborn Independent) as well as many of Fritsch's own works.

An inflammatory article published in 1910 earned him a charge of defamation of religious societies and disturbing the public peace.

Members of these groups formed the Thule Society in 1918, which eventually sponsored the creation of the Nazi Party.

The Reichshammerbund was eventually folded into the Deutschvölkischer Schutz und Trutzbund (German Nationalist Protection and Defiance Federation), on whose advisory board Fritsch sat.

In 1893, Fritsch published his most famous work, The Handbook of the Jewish Question, which leveled a number of conspiratorial charges at European Jews and called upon Germans to refrain from intermingling with them.

The ideas espoused by the work greatly influenced Hitler and the Nazis during their rise to power after World War I.

[citation needed] Fritsch also founded an anti-semitic journal – the Hammer – in 1902, and this became the basis of a movement, the Reichshammerbund, in 1912.