Pythagorean theorem

When Euclidean space is represented by a Cartesian coordinate system in analytic geometry, Euclidean distance satisfies the Pythagorean relation: the squared distance between two points equals the sum of squares of the difference in each coordinate between the points.

English mathematician Sir Thomas Heath gives this proof in his commentary on Proposition I.47 in Euclid's Elements, and mentions the proposals of German mathematicians Carl Anton Bretschneider and Hermann Hankel that Pythagoras may have known this proof.

Heath himself favors a different proposal for a Pythagorean proof, but acknowledges from the outset of his discussion "that the Greek literature which we possess belonging to the first five centuries after Pythagoras contains no statement specifying this or any other particular great geometric discovery to him.

"[3] Recent scholarship has cast increasing doubt on any sort of role for Pythagoras as a creator of mathematics, although debate about this continues.

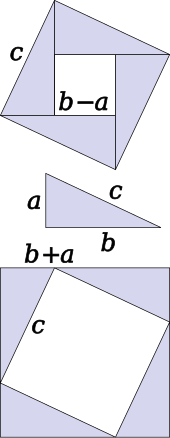

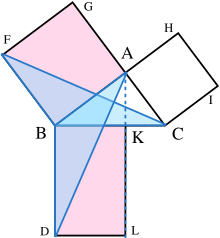

[4] The theorem can be proved algebraically using four copies of the same triangle arranged symmetrically around a square with side c, as shown in the lower part of the diagram.

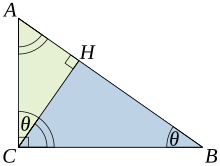

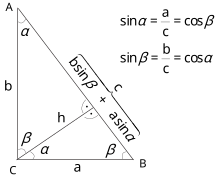

These ratios can be written as Summing these two equalities results in which, after simplification, demonstrates the Pythagorean theorem: The role of this proof in history is the subject of much speculation.

[27][28] A corollary of the Pythagorean theorem's converse is a simple means of determining whether a triangle is right, obtuse, or acute, as follows.

The reciprocal Pythagorean theorem is a special case of the optic equation where the denominators are squares and also for a heptagonal triangle whose sides

One of the consequences of the Pythagorean theorem is that line segments whose lengths are incommensurable (so the ratio of which is not a rational number) can be constructed using a straightedge and compass.

Pythagoras' theorem enables construction of incommensurable lengths because the hypotenuse of a triangle is related to the sides by the square root operation.

The figure on the right shows how to construct line segments whose lengths are in the ratio of the square root of any positive integer.

A typical example where the straight-line distance between two points is converted to curvilinear coordinates can be found in the applications of Legendre polynomials in physics.

By rearranging the following equation is obtained This can be considered as a condition on the cross product and so part of its definition, for example in seven dimensions.

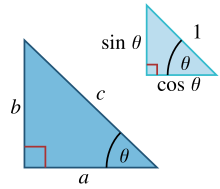

Taking the ratio of sides opposite and adjacent to θ, Likewise, for the reflection of the other triangle, Clearing fractions and adding these two relations: the required result.

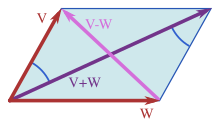

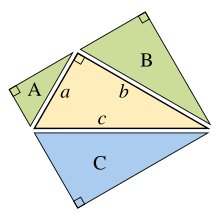

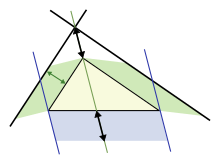

This replacement of squares with parallelograms bears a clear resemblance to the original Pythagoras' theorem, and was considered a generalization by Pappus of Alexandria in 4 AD[49][50] The lower figure shows the elements of the proof.

The length of face diagonal AC is found from Pythagoras' theorem as: where these three sides form a right triangle.

Using diagonal AC and the horizontal edge CD, the length of body diagonal AD then is found by a second application of Pythagoras' theorem as: or, doing it all in one step: This result is the three-dimensional expression for the magnitude of a vector v (the diagonal AD) in terms of its orthogonal components {vk} (the three mutually perpendicular sides): This one-step formulation may be viewed as a generalization of Pythagoras' theorem to higher dimensions.

However, this result is really just the repeated application of the original Pythagoras' theorem to a succession of right triangles in a sequence of orthogonal planes.

The "hypotenuse" is the base of the tetrahedron at the back of the figure, and the "legs" are the three sides emanating from the vertex in the foreground.

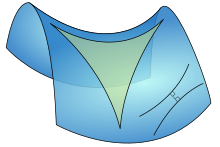

In a different wording:[52] Given an n-rectangular n-dimensional simplex, the square of the (n − 1)-content of the facet opposing the right vertex will equal the sum of the squares of the (n − 1)-contents of the remaining facets.The Pythagorean theorem can be generalized to inner product spaces,[53] which are generalizations of the familiar 2-dimensional and 3-dimensional Euclidean spaces.

If v1, v2, ..., vn are pairwise-orthogonal vectors in an inner-product space, then application of the Pythagorean theorem to successive pairs of these vectors (as described for 3-dimensions in the section on solid geometry) results in the equation[57] Another generalization of the Pythagorean theorem applies to Lebesgue-measurable sets of objects in any number of dimensions.

For practical computation in spherical trigonometry with small right triangles, cosines can be replaced with sines using the double-angle identity

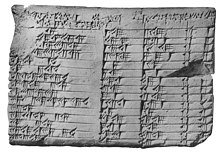

Historians of Mesopotamian mathematics have concluded that the Pythagorean rule was in widespread use during the Old Babylonian period (20th to 16th centuries BC), over a thousand years before Pythagoras was born.

The Mesopotamian tablet Plimpton 322, written near Larsa also c. 1800 BC, contains many entries closely related to Pythagorean triples.

[72] In India, the Baudhayana Shulba Sutra, the dates of which are given variously as between the 8th and 5th century BC,[73] contains a list of Pythagorean triples and a statement of the Pythagorean theorem, both in the special case of the isosceles right triangle and in the general case, as does the Apastamba Shulba Sutra (c. 600 BC).

[a] Byzantine Neoplatonic philosopher and mathematician Proclus, writing in the fifth century AD, states two arithmetic rules, "one of them attributed to Plato, the other to Pythagoras",[76] for generating special Pythagorean triples.

The rule attributed to Pythagoras (c. 570 – c. 495 BC) starts from an odd number and produces a triple with leg and hypotenuse differing by one unit; the rule attributed to Plato (428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) starts from an even number and produces a triple with leg and hypotenuse differing by two units.

[78][79] Classicist Kurt von Fritz wrote, "Whether this formula is rightly attributed to Pythagoras personally ... one can safely assume that it belongs to the very oldest period of Pythagorean mathematics.

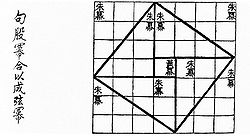

[80] With contents known much earlier, but in surviving texts dating from roughly the 1st century BC, the Chinese text Zhoubi Suanjing (周髀算经), (The Arithmetical Classic of the Gnomon and the Circular Paths of Heaven) gives a reasoning for the Pythagorean theorem for the (3, 4, 5) triangle — in China it is called the "Gougu theorem" (勾股定理).

[81][82] During the Han Dynasty (202 BC to 220 AD), Pythagorean triples appear in The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art,[83] together with a mention of right triangles.

(The area of the white space remains constant throughout the translation rearrangement of the triangles. At all moments in time, the area is always c 2 . And likewise, at all moments in time, the area is always a 2 + b 2 .)

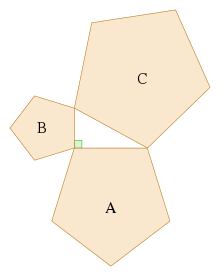

green area A + B = blue area C

green area = blue area