Theories about Stonehenge

According to Geoffrey's Historia Regum Britanniae, when asked what might serve as an appropriate burial place for Britain's dead princes, Merlin advised King Aurelius Ambrosius to raise an army and collect some magical stones from Mount Killarus in Ireland.

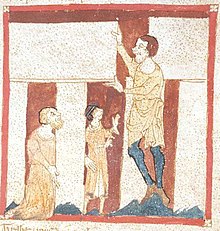

Whilst at Mount Killarus, Merlin laughed at the soldiers' failed attempts to remove the stones using ladders, ropes, and other machinery.

Shortly thereafter, Merlin oversaw the removal of stones using his own machinery and commanded they be loaded onto the soldiers' ships and sailed back to England where they were reconstructed into Stonehenge.

The classical Greek writer Diodorus Siculus (1st century BC) may refer to Stonehenge in a passage from his Bibliotheca historica.

Citing the 4th-century BC historian Hecataeus of Abdera and "certain others", Diodorus says that in "a land beyond the Celts" (i.e. Gaul) there is "an island no smaller than Sicily" in the northern sea called Hyperborea, so named because it is beyond the source of the north wind or Boreas.

[6][7][8] Christopher Chippindale commented that "This might be Stonehenge, but the description is short and vague, and there are discrepancies = the climate of the Hyperboreans is so mild they grow two crops a year.

An oval-shaped setting of bluestones similar to those at Stonehenge 3iv occurs at Bedd Arthur in the Preseli Hills, but that does not imply a direct cultural link.

Recent analysis of contemporary burials found nearby known as the Boscombe Bowmen, has indicated that at least some of the individuals associated with Stonehenge 3 came either from Wales or from some other European area of ancient rocks.

Aubrey Burl and a number of geologists and geomorphologists contend that the bluestones were not transported by human agency at all and were instead brought by glaciers at least part of the way from Wales during the Pleistocene.

[14] Britain's Geoffrey Wainwright, president of the London Society of Antiquaries, and Timothy Darvill, on 22 September 2008, speculated that it may have been an ancient healing and pilgrimage site,[16] since burials around Stonehenge showed trauma and deformity evidence: "It was the magical qualities of these stones which ... transformed the monument and made it a place of pilgrimage for the sick and injured of the Neolithic world."

[17] It could be the primeval equivalent of Lourdes, since the area was already visited 4,000 years before the oldest stone circle, and attracted visitors for centuries after its abandonment.

[18][19] Some tentative support for this view comes from the first-century BC Greek historian, Diodorus Siculus, who cites a lost account set down three centuries earlier, which described "a magnificent precinct sacred to Apollo and a notable spherical temple" on a large island in the far north, opposite what is now France.

[23] According to Kelly's theory, Stonehenge served the purpose of a mnemonic centre for recording and retrieving knowledge by Neolithic Britons, who lacked written language.

Many archaeologists believe Stonehenge was an attempt to render in permanent stone the more common timber structures that dotted Salisbury Plain at the time, such as those that stood at Durrington Walls.

Modern anthropological evidence has been used by Mike Parker Pearson and the Malagasy archaeologist Ramilisonina to suggest that timber was associated with the living and stone with the ancestral dead amongst prehistoric peoples.

There is no satisfactory evidence to suggest that Stonehenge's astronomical alignments were anything more than symbolic and current interpretations favour a ritual role for the monument that takes into account its numerous burials and its presence within a wider landscape of sacred sites.

Support for this view also comes from the historian of religions Mircea Eliade, who compares the site to other megalithic constructions around the world devoted to the cult of the dead (ancestors).

Like other similar English monuments [For example, Eliade identifies, Woodhenge, Avebury, Arminghall, and Arbor Low] the Stonehenge cromlech was situated in the middle of a field of funeral barrows.

We have the same valourisation of the sacred space as "centre of the world," the privileged place that affords communication with heaven and the underworld, that is, with the gods, the chtonian goddesses, and the spirits of the dead.

[25]In addition to the English sites, Eliade identifies, among others, the megalithic architecture of Malta, which represents a "spectacular expression" of the cult of the dead and worship of a Great Goddess.

This natural solstitial alignment would have symbolized cosmic unity to the ancients, a place where Heaven and Earth were unified by some supernatural force.

[28] According to architect and archaeologist Didier Laroche, it is a funerary monument with a central courtyard that was originally partially included in a tumulus and of which only the stone structures remained, as is the case for many other megalithic tombs.

This is very significant in respect of the Great Trilithon; the surviving upright has its flatter face outwards (see image on right), towards the midwinter sunset, and was raised from the inside.

Assuming the bluestones were brought from Wales by hand, and not transported by glaciers as Aubrey Burl has claimed, various methods of moving them relying only on timber and rope have been suggested.

In a 2001 exercise in experimental archaeology, an attempt was made to transport a large stone along a land and sea route from Wales to Stonehenge.

Volunteers pulled it for some miles (with great difficulty) on a wooden sledge over land, using modern roads and low-friction netting to assist sliding, but it became clear that it would have been incredibly difficult for even the most organized of tribal groups to have pulled large numbers of stones across the densely wooded, rough and boggy terrain of West Wales.

In 2010, Nova's "Secrets of Stonehenge" broadcast an effective technique for moving the stones over short distances using ball bearings in a wooden track as originally envisioned by Andrew Young, a graduate student of Bruce Bradley—director of experimental archaeology at the University of Exeter.

[31] In 1997 Julian Richards teamed up with Mark Witby and Roger Hopkins to conduct several experiments to replicate the construction at Stonehenge for Nova's "Secrets of Lost Empires" mini series.

In 2003 retired construction worker Wally Wallington demonstrated ingenious techniques based on fundamental principles of levers, fulcrums and counterweights to show that a single man can rotate, walk, lift and tip a ten-ton cast-concrete monolith into an upright position.

British author John Michell wrote that Alfred Watkins's ley lines appeared to be in alignment with various traditional sacred sites around the country, such as the 'Perpetual Choirs' apparently mentioned in the Welsh Triads.