Theory of Colours

The work originated in Goethe's occupation with painting and primarily had its influence in the arts, with painters such as (Philipp Otto Runge, J. M. W. Turner, the Pre-Raphaelites, Hilma af Klint, and Wassily Kandinsky).

Goethe's book provides a catalogue of how colour is perceived in a wide variety of circumstances, and considers Isaac Newton's observations to be special cases.

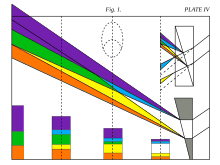

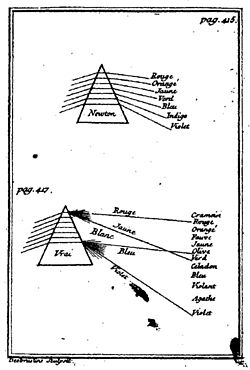

At Goethe's time, it was generally acknowledged that, as Isaac Newton had shown in his Opticks in 1704, colourless (white) light is split up into its component colours when directed through a prism.

[9] "Whereas Newton observed the colour spectrum cast on a wall at a fixed distance away from the prism, Goethe observed the cast spectrum on a white card which was progressively moved away from the prism... As the card was moved away, the projected image elongated, gradually assuming an elliptical shape, and the coloured images became larger, finally merging at the centre to produce green.

Moving the card farther led to the increase in the size of the image, until finally the spectrum described by Newton in the Opticks was produced...

If the density of such a medium be increased, or if its volume become greater, we shall see the light gradually assume a yellow-red hue, which at last deepens to a ruby colour.

He then proceeds with numerous experiments, systematically observing the effects of rarefied mediums such as dust, air, and moisture on the perception of colour.

Varying the experimental conditions by using different shades of grey shows that the intensity of coloured edges increases with boundary contrast.

By placing his prism in full sunlight, and placing a black cardboard circle in the middle the same size as Newton's hole — a dark spectrum (i.e., a shadow surrounded by light) is produced; we find there a violet-blue along the top edge, and red-yellow along the bottom edge—and where these edges overlap, we find (extraspectral) magenta.

He writes, "The chromatic circle... [is] arranged in a general way according to the natural order... for the colours diametrically opposed to each other in this diagram are those which reciprocally evoke each other in the eye.

In the same way that light and dark spectra yielded green from the mixture of blue and yellow—Goethe completed his colour wheel by recognising the importance of magenta—"For Newton, only spectral colors could count as fundamental.

These six qualities were assigned to four categories of human cognition, the rational (Vernunft) to the beautiful and the noble (red and orange), the intellectual (Verstand) to the good and the useful (yellow and green), the sensual (Sinnlichkeit) to the useful and the common (green and blue) and, closing the circle, imagination (Phantasie) to both the unnecessary and the beautiful (purple and red).

If one observes the colours coming out of a prism—an English person may be more inclined to describe as magenta what in German is called Purpur—so one may not lose the intention of the author.

It is not clear how Goethe's Rot, Purpur (explicitly named as the complementary to green),[26] and Schön (one of the six colour sectors) are related between themselves and to the red tip of the visible spectrum.

It would be superficial to dismiss this struggle as unimportant: there is much significance in one of the most outstanding men directing all his efforts to fighting against the development of Newtonian optics."

Whereas Newton narrowed the beam of light in order to isolate the phenomenon, Goethe observed that with a wider aperture, there was no spectrum.

In a letter written to Count Semyon Romanovich Vorontsov (1792), Miranda recounted how Goethe, fascinated with his exploits throughout the Americas and Europe, told him, "Your destiny is to create in your land a place where primary colours are not distorted."

[40][better source needed]In the nineteenth century Goethe's Theory was taken up by Schopenhauer in On Vision and Colors, who developed it into a kind of arithmetical physiology of the action of the retina, much in keeping with his own representative idealism ["The world is my representation or idea"].

Among these — just under half spoke against Goethe, especially Thomas Young, Louis Malus, Pierre Prévost and Gustav Theodor Fechner.

(Helmholtz 1853)[42] Although the accuracy of Goethe's observations does not admit a great deal of criticism, his aesthetic approach did not lend itself to the demands of analytic and mathematical analysis used ubiquitously in modern science.

Goethe was not interested in Newton's analytic treatment of colour—but he presented an excellent rational description of the phenomenon of human colour perception.

And Goethe's insight is surprisingly significant, because he correctly claimed that all of the results of Newton's prism experiments fit a theoretical alternative equally well.. a century before Duhem and Quine's famous arguments for Underdetermination.

The critique maintained that Newton had mistaken mathematical imagining as the pure evidence of the senses.. Goethe tried to define the scientific function of imagination: to interrelate phenomena once they have been meticulously produced, described, and organized... Newton had introduced dogma.. into color science by claiming that color could be reduced to a function of rays."

Whereas Newton sought to develop a mathematical model for the behaviour of light, Goethe focused on exploring how colour is perceived in a wide array of conditions.

[2] Goethe discovered that producing images by passing inverse optical contrasts through a prism always results in isomorphic, complementary spectra.

Experimental developments by physicist Matthias Rang have demonstrated Goethe's discovery of complementarity as a symmetric property of spectral phenomena.

It is then shown that both these properties are approximations that apply under the specific conditions that have later become standardized in Spectroscopy, leading to a consensus regarding the relation of wavelength to colours of one particular spectrum.

His last things are insipid.Aber wie verwundert war ich, als die durch's Prisma angeschaute weiße Wand nach wie vor weiß blieb, daß nur da, wo ein Dunkles dran stieß, sich eine mehr oder weniger entschiedene Farbe zeigte, daß zuletzt die Fensterstäbe am allerlebhaftesten farbig erschienen, indessen am lichtgrauen Himmel draußen keine Spur von Färbung zu sehen war.

Es bedurfte keiner langen Überlegung, so erkannte ich, daß eine Gränze nothwendig sey, um Farben hervorzubringen, und ich sprach wie durch einen Instinct sogleich vor mich laut aus, daß die Newtonische Lehre falsch sey.

It didn't take long before I knew that a border was required for colour to be brought forth, and I spoke as through an instinct out loud, that the Newtonian teachings were false.