Ancient Macedonian army

Initially of little account in the Greek world, it was widely regarded as a second-rate power before being made formidable by Philip II, whose son and successor Alexander the Great conquered the Achaemenid Empire in just over a decade's time.

By 338 BC, more than a half of the army for his planned invasion of the Achaemenid Empire came from outside of Macedon's borders—from all over the Greek world and the nearby barbarian tribes, such as the Illyrians, the Paeonians, and the Thracians.

[3] The foot companions existed perhaps since the reign of Alexander I of Macedon, while Macedonian troops are accounted for in the history of Herodotus as subjects of the Persian Empire fighting the Greeks at the Battle of Plataea in 479 BC.

[8] However, Malcolm Errington cautions that any figures for Macedonian troop sizes provided by ancient authors should be treated with a degree of skepticism, since there are very few means by which modern historians are capable of confirming their veracity (and could have been possibly lower or even higher than the numbers stated).

[10] As a political counterbalance to the native-born Macedonian nobility, Philip invited military families from throughout Greece to settle on lands he had conquered or confiscated from his enemies, these 'personal clients' then also served as army officers or in the Companion cavalry.

After taking control of the gold-rich mines of Mount Pangaeus, and the city of Amphipolis that dominated the region, he obtained the wealth to support a large army.

By the time of his death, Philip's army had pushed the Macedonian frontier into southern Illyria, conquered the Paeonians and Thracians, asserted a hegemony over Thessaly, destroyed the power of Phocis and defeated and humbled Athens and Thebes.

[11] One important military innovation of Philip II is often overlooked, he banned the use of wheeled transport and limited the number of camp servants to one to every ten infantrymen and one each for the cavalry.

[12] The Companion cavalry, or Hetairoi (Ἑταῖροι), were the elite arm of the Macedonian army, and were the offensive force that made the decisive attack in most of the battles of Alexander the Great.

However, the ancient historian Arrian implies that the Companion cavalry were successful in an assault, along with heavy infantry, on the Greek mercenary hoplites serving Persia in the closing stages of the Battle of Granicus.

[24] The Thessalian heavy cavalry accompanied Alexander during the first half of his Asian campaign and continued to be employed by the Macedonians as allies until Macedon's final demise at the hands of the Romans.

[29] Apart from the prodromoi (in the sense of a single unit), other horsemen from subject or allied nations, filling various tactical roles and wielding a variety weapons, rounded out the cavalry.

By the time Alexander campaigned in India, and subsequently, the cavalry had been drastically reformed and included thousands of horse-archers from Iranian peoples such as the Dahae (prominent at the Battle of Hydaspes).

[38] Diodorus claimed that Philip was inspired to make changes in the organisation of his Macedonian infantry from reading a passage in the writings of Homer describing a close-packed formation.

[51] In terms of weaponry, they were probably equipped in the style of a traditional Greek hoplite with a thrusting spear or doru (shorter and less unwieldy than the sarissa) and a large round shield.

When taking part in rapid forced marches or combat in broken terrain, so common in the eastern Persian Empire, it appears that they wore little more than a helmet and a cloak (exomis) so as to enhance their stamina and mobility.

[58] The army led by Alexander the Great into the Persian Empire included Greek heavy infantry in the form of allied contingents provided by the League of Corinth and hired mercenaries.

It is unclear if the Thracians, Paeonians, and Illyrians fighting as javelin throwers, slingers, and archers serving in Macedonian armies from the reign of Philip II onward were conscripted as allies via a treaty or were simply hired mercenaries.

[63] Peltasts were armed with a number of javelins and a sword, carried a light shield but wore no armour, though they sometimes had helmets; they were adept at skirmishing and were often used to guard the flanks of more heavily equipped infantry.

Certainly, cavalry, including Alexander himself, fought on foot during sieges and assaults on fortified settlements, phalangites are described using javelins and some infantrymen were trained to ride horses.

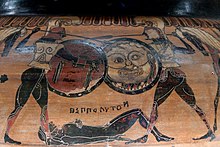

The straight-bladed shortsword known as the xiphos (ξίφος) is depicted in works of art, and two types of single-edged cutting swords, the kopis and machaira, are shown in images and are mentioned in texts.

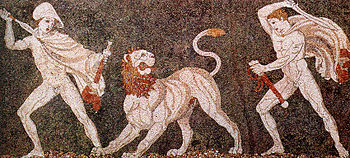

[90] Additionally, a fresco depicting a Macedonian mounted lancer spearing an infantryman, from the Kinch Tomb, near Naousa, shows the cavalryman wearing a Thracian type helmet.

The Alexander Mosaic suggests that officers of the heavy cavalry had rank badges in the form of laurel wreaths (perhaps painted or constructed from metal foil) on their helmets.

Other forms of armour are mentioned in original sources, such as the kotthybos and a type of "half-armour" the hemithorakion (ἡμιθωράκιον); the precise nature of these defences is not known but it would be reasonable to conclude that they were lighter and perhaps afforded less protection than the thorax.

[104] Xenophon mentions a type of armour called "the hand" to protect the left, bridle, arm of heavy cavalrymen, though there is no supporting evidence for its widespread use.

This probably meant that, as both hands were needed to hold the sarissa, the shield was worn suspended by a shoulder strap and steadied by the left forearm passing through the armband.

Torsion machines used skeins of sinew or hair rope, which were wound around a frame and twisted so as to power two bow arms; these could develop much greater force than earlier forms (such as the gastraphetes) reliant on the elastic properties of a bow-stave.

These structures, which were wheeled and several stories high, were covered with wet hide or metal sheathing to protect from missile fire, especially incendiaries, and the largest might be equipped with artillery.

The oblique advance with the left refused, the careful manoeuvring to create disruption in the enemy formation and the knock out charge of the strong right wing, spearheaded by the Companion cavalry, became standard Macedonian practice.

The phalanx finally met its end in the Ancient world when the more flexible Roman manipular tactics contributed to the defeat and partition of Macedon in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC.