History of Ghana

Various aspects of Akan culture stem from the Bono state, including the umbrella used for the kings, the swords of the nation, the stools or thrones, goldsmithing, blacksmithing, Kente Cloth weaving, and goldweighing.

[35][34] Osei Tutu was strongly influenced by the high priest, Anokye, who, tradition asserts, caused a stool of gold to descend from the sky to seal the union of Ashanti states.

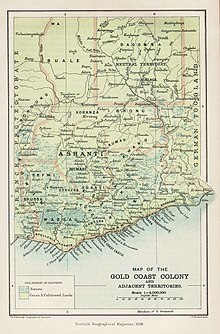

The wars of expansion that brought the northern states of Dagomba,[39] Mamprusi, and Gonja[40] under Ashanti influence were won during the reign of Opoku Ware I (died 1750), successor to Osei Kofi Tutu I.

[19][41] When the first European colonizers arrived in the late 15th century, many inhabitants of the Gold Coast area were striving to consolidate their newly acquired territories and to settle into a secure and permanent environment.

[66] Maclean's exercise of limited judicial power on the coast was so effective that a parliamentary committee recommended that the British government permanently administer its settlements and negotiate treaties with the coastal chiefs that would define Britain's relations with them.

[120] The development of national consciousness accelerated quickly in the post-World War II era, when, in addition to ex-servicemen, a substantial group of urban African workers and traders emerged to lend mass support to the aspirations of a small educated minority.

[121][122] By the late 19th century, a growing number of educated Africans increasingly found unacceptable an arbitrary political system that placed almost all power in the hands of the governor through his appointment of council members.

[134] Change that would place real power in African hands was not a priority among British leaders until after rioting and looting in Accra and other towns and cities in early 1948 over issues of pensions for ex-servicemen, the dominant role of settler-colonists in the economy, the shortage of housing, and other economic and political grievances.

World War II had just ended, and many Gold Coast veterans who had served in British overseas expeditions returned to a country beset with shortages, inflation, unemployment, and black-market practices.

[136] They were now joined by farmers, who resented drastic governmental measures required to cut out diseased cacao trees in order to control an epidemic, and by many others who were unhappy that the end of the war had not been followed by economic improvements.

[127] Although political organizations had existed in the British colony, the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC), founded on 4 August 1947 by educated Ghanaians known as The Big Six, was the first nationalist movement with the aim of self-government "in the shortest possible time."

[166] Government expenditure on road building projects, mass education of adults and children, and health services, as well as the construction of the Akosombo Dam, were all important if Ghana were to play its leading role in Africa's liberation from colonial and neo-colonial domination.

Later, Adamafio was appointed minister of state for presidential affairs, the most important post in the president's staff at Flagstaff House, which gradually became the centre for all decision making and much of the real administrative machinery for both the CPP and the government.

After a bomb attempt on Nkrumah's life in August 1962, Adamafio, Ako Adjei (then minister of foreign affairs), and Cofie Crabbe (all members of the CPP) were jailed under the Preventive Detention Act.

[181] Politically, allegations and instances of corruption in the ruling party, and in Nkrumah's personal finances, undermined the very legitimacy of his regime and sharply decreased the ideological commitment needed to maintain the public welfare under Ghanaian socialism.

[176][187] Leaders of the 1966 military coup justified their takeover by charging that the CPP administration was abusive and corrupt, that Nkrumah's involvement in African politics was overly aggressive, and that the nation lacked democratic practices.

[189] Despite the vast political changes that were brought about by the overthrow of Kwame Nkrumah, many problems remained, including ethnic and regional divisions, the country's economic burdens, and mixed emotions about a resurgence of an overly strong central authority.

[199] In Ghana's 1969 elections, the first competitive nationwide political contest since 1956, the major contenders were the Progress Party (PP), headed by Kofi Abrefa Busia, and the National Alliance of Liberals (NAL), led by Komla A.

After a brief period under an interim three-member presidential commission, the electoral college chose as president Chief Justice Edward Akufo-Addo, one of the leading nationalist politicians of the UGCC era and one of the judges dismissed by Nkrumah in 1964.

[216] The recovery measures also severely affected the middle class and the salaried work force, both of which faced wage freezes, tax increases, currency devaluations, and rising import prices.

[221] Important questions about developmental priorities remained unanswered, and after the failure of both the Nkrumah and the Busia regimes (one a one-party state, and the other a multi-party parliamentary democracy) Ghana's path to political stability was obscure.

[222] Acheampong's National Redemption Council (NRC) claimed that it had to act to remove the ill effects of the currency devaluation of the previous government and thereby, at least in the short run, to improve living conditions for individual Ghanaians.

[222] In matters of economic policy, Busia's austerity measures were reversed, the Ghanaian currency was revalued upward, foreign debt was repudiated or unilaterally rescheduled, and all large foreign-owned companies were nationalized.

Naomi Chazan, a leading analyst of Ghanaian politics, assessed the significance of the 1979 coup:[236] Unlike the initial SMC II [the Akuffo period, 1978–1979] rehabilitation effort which focused on the power elite, this second attempt at reconstruction from a situation of disintegration was propelled by growing alienation.

Calling itself the Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC), its membership included Rawlings as chairman, Brigadier Joseph Nunoo-Mensah (whom Limann had dismissed as army commander), two other officers, and three civilians.

With regard to public boards and statutory corporations, excluding banks and financial institutions, Joint Consultative Committees (JCCs) that acted as advisory bodies to managing directors were created.

The magnitude of the crisis—made worse by widespread bush fires that devastated crop production in 1983–1984 and by the return of more than one million Ghanaians who had been expelled from Nigeria in 1983, which had intensified the unemployment situation—called for monetary assistance from institutions with bigger financial chests.

"[244] After two years of deliberations and public hearings, the NCD recommended the formation of district assemblies as local governing institutions that would offer opportunities to the ordinary person to become involved in the political process.

As I said in my nationwide broadcast on December 31, if we are to see a sturdy tree of democracy grow, we need to learn from the past and nurture very carefully and deliberately political institutions that will become the pillars upon which the people's power will be erected.

[244]Rawlings's explanation notwithstanding, various opposition groups continued to describe the PNDC-proposed district assemblies as a mere public relations ploy designed to give political legitimacy to a government that had come to power by unconstitutional means.

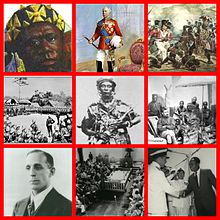

- Asantehene Osei Kofi Tutu I

- Major General Sir Garnet Wolseley

- Anglo-Ashanti wars

- British delegation to Kumasi in the 19th century

- Queen Yaa Asantewaa

- Asantehene Kwaku Dua II

- Arnold Weinholt Hodson

- Gold Coast Legislative Assembly

- Kwame Nkrumah as Prime Minister