Thomas Abernethy (explorer)

[2] In 1829, Abernethy married Barbara Fiddes, the daughter of a ship's carpenter, and they lived at Deptford, southeast London, near the Royal Naval docks.

In 1829, John Ross described him as "decidedly the best-looking man in the ship" and he thought that men of his appearance were best able to endure cold.

Leaving London in May 1824, the expedition reached Lancaster Sound, but they had to winter at the Brodeur Peninsula in the northwest part of Baffin Island, due to ice.

[note 4] Departing London in March 1827, they sailed to Spitsbergen where they found a safe anchorage at Sorgfjorden, Ny-Friesland, in the far north.

[10] In 1829, Sir John Ross led another Northwest Passage expedition and appointed Abernethy as second mate to join the crew of Victory, a sailing ship and steam paddle steamer of 30 horsepower.

By October they had reached Prince Regent Inlet and then far south into the Gulf of Boothia where they anchored for the winter at Felix Harbour.

A small party led by James Ross, including Abernethy, explored northwards but were unable to locate Bellot Strait.

They went a way down the northwest coast of the island and then, 200 miles in a direct line from their ship, they returned on 13 June – after a journey of one month they looked like "human skeletons".

[15][16][17] Ross decided to explore a few miles further north before turning back so he chose Abernethy as his sole companion.

Through the winter they hunted for food – as well as catching seals Abernethy was good at shooting hares and grouse so becoming called "the gamekeeper".

[19] A three-strong advance party, including Abernethy, located the scene of Fury's wreckage and the entire expedition was able to use the stores and boats left there and build a substantial shelter, "Somerset House".

In July Prince Regent Inlet cleared of ice but by August they found Lancaster Sound completely blocked so they had to return to Fury Beach for the next winter in Somerset House.

[19] By the time they reached Hull, where they received a civic reception, they had been away for four years and 149 days – Abernethy was paid £329:14:8d in back pay at double rates.

McCormick (from Parry's north polar days) who was ships' surgeon and Abernethy became close associates – and in New Zealand the pair collected natural history specimens.

Amundsen wrote "Few people of the present day are capable of rightly appreciating this heroic deed, this brilliant proof of human courage and energy ...

These men were heroes ...", and Scott wrote "... all must concede that it deserves to rank among the most brilliant and famous [Antarctic expeditions] that have been made.

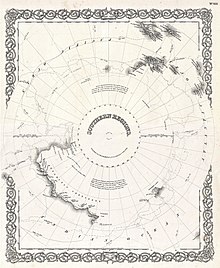

... few things could have looked more hopeless than an attack upon the great ice-bound region" They then emerged into open sea at 69°15′S and, sailing further south hoping to reach the South Magnetic Pole, they spotted land and mountains which they named Victoria Land and the Admiralty Range, and cleared Cape Adare.

[23] Soon, in the distance, they spotted what McCormick described as "a stupendous volcanic mountain in a high state of activity" and, getting closer, "a dense column of black smoke, intermingled with flashes of red flame".

At a low point in the ice cliffs they could see from the masthead "an enormous plain of frosted silver" and they were certain there was no open sea further south.

After passing Cape Adare, they again succeeded in breaking through the pack ice and reached Tasmania on 6 April 1841 to be greeted by John Franklin and crowds of well-wishers.

This time they failed to penetrate any distance into the pack ice so they retreated, heading for the Cape of Good Hope arriving in April 1843, and sailing home via St Helena, Ascension Island and Rio de Janeiro.

Early next season they carefully checked in Peel Sound by sledge, not realising this had actually been Franklin's route, and returned to Enterprise after 500 miles and 39 days.

[28] The Admiralty offered rewards for finding (or even hearing news of) Franklin so the 73-year-old John Ross set off with Felix, a steam schooner, with Abernethy as master of the vessel.

Felix left Ayr on 20 May 1850 but at Loch Ryan in a near mutiny many of the crew had gone ashore and got drunk so Ross had to leave eight of them behind, including Abernethy himself.

A letter from Ross to the Hudson's Bay Company and a report in the Shipping Gazette were bitterly critical of Abernethy, blaming him for instigating the whole thing.

Sailing on north they reached Smith Sound and discovered it provided a hitherto unknown entrance to the Arctic Ocean.

On 29 August, with a heavy swell, thick fog, and ice forming, on Abernethy's advice that they only had four or five days before they would be trapped, they turned to the south and reached Beechey Island to leave surplus stores for the ships there.

[note 9][34] According to Alex Buchan, Abernethy's biographer, in the 19th century Royal Naval officers were almost always from the landed gentry and they had purchased their commissions.

[35] Although Abernethy has largely disappeared from history his contributions were sufficiently outstanding for accounts to have been left of him, even though he was neither an officer nor a gentleman.