Thomas McKeown (physician)

The seeds of his work can be found in four seminal papers published in the academic journal Population Studies,[3][4][5][6] a book on Medicine in Modern Society in 1965,[7] and a textbook (with C.R.

[10] In his last book, The Origins of Human Disease, published shortly after he died in 1988, he had found a milder tone to express his critical relativism of medicine and health.

In the 1970s, an era wherein all aspects of social, economic and cultural establishment were challenged, McKeown found a receptive audience with other health critics such as Ivan Illich.

[18] By some researchers, including the economist and Nobel prize winner Angus Deaton, McKeown is considered as 'the founder of social medicine'.

[20][21] McKeown repeatedly urged readers to rethink public health, medical care and social policy, implying that this would have political and financial benefits.

[22] What makes it even more complicated to value McKeown's work and its consequences is that he himself shaped and reshaped his ideas in a career that spans more than five decades, from his first publication in 1934[23] to his last book on The Origins of Human Disease in 1988.

[24][25] Particularly the work of Nobel economic laureates Robert W. Fogel (1993)[26][27][28][29] and Angus Deaton (2015) have greatly contributed to the recent reappreciation of the McKeown thesis: 'McKeown's views, updated to modern circumstances, are still important today in debates between those who think that health is primarily determined by medical discoveries and medical treatment and those who look to the background social conditions of life.'

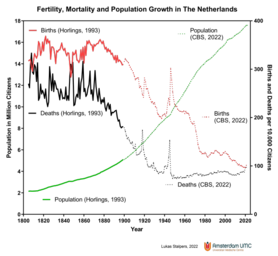

(Angus Deaton,[19] page 91) Nowadays, very few will disagree with McKeown that the late 19th century surge of the population in the western world can be mainly ascribed to a fall in mortality and not to a rise in fertility.

Benson (1976) in a critical review of his book wrote that McKeown had insufficiently shown 'that it was mortality that fell and not fertility that rose to cause the population growth'.

[34] Among many valuable findings on historical demography, and for the pre-industrial time largely based on studies of parish registers, they may in hindsight have overinterpreted the frequent birth peaks as evidence that an increase of the birth-rate was the predominant influence before the mid-nineteenth century.

[35] Furthermore, as McKeown explained, it is very hard to biologically understand how a higher standard of living in early industrialisation could have selectively favoured fertility without decreasing mortality.

[11] Ten years later, Schofield and Reher (1991) were already far more appreciative of McKeown's work, not only that his controversial ideas had enormously boosted research of historical demography, but also that he proofed to be right on many points.

This doubt was probably cast by an idealisation of the living conditions of pre-historical hunters and gatherers, or by a nostalgic call for a return to the flower power of ancient agricultural life.

[11] McKeown was not blind to the social misery which was introduced by industrialisation, which led to overcrowded cities, poor housing, worsening of personal hygiene, foul drinking water, child labour and dangerous working conditions.

Flinn (1971) already found for the pre-industrial 18th century that mortality crises were less than in the 17th century, and explained that by reduced fluctuations in food prices and fewer and less severe periods of famine by increased food imports during periods of failed crops, and by an agricultural transition from monoculture (grain) to more diverse products (rice, maize and buckwheat in the south, and potatoes in the north).

[31] Particularly the valuable work on the technophysio evolution by Nobel prize laureate economist Robert Fogel and collaborators has contributed to the acceptance of McKeown's thesis.

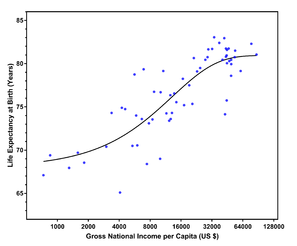

Knibbe (2007) combined physiological indicators of health with economical data and discovered a direct relation between food intake, food price and health in the Netherlands of the 19th century; he for instance described a consistent relation between caloric intake and body length of Dutch conscripts between 1807 and the late 19th century (see Figure).

Most contributors by now acknowledged the importance of an improved standard of living in the decline of mortality, both in 19th century Europe as in present-day developing countries.

It was no longer disputed that food was indispensable for a decrease in mortality,[41] but that other environmental improvements which came with more wealth, i.e. hygienic measures, had to work at the same time.

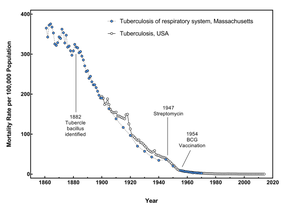

An example that he repeatedly used was the falling mortality from tuberculosis in England and Wales since the 19th century, well before the introduction of the first effective antibiotic drug in 1947 and BCG vaccination in 1954.