Thomas Nagel

He continued the critique of reductionism in Mind and Cosmos (2012), in which he argues against the neo-Darwinian view of the emergence of consciousness.

He then attended the University of Oxford on a Fulbright Scholarship and received a BPhil in philosophy in 1960; there, he studied with J. L. Austin and Paul Grice.

For contingent, limited and finite creatures, no such unified world view is possible, because ways of understanding are not always better when they are more objective.

Like the British philosopher Bernard Williams, Nagel believes that the rise of modern science has permanently changed how people think of the world and our place in it.

A modern scientific understanding is one way of thinking about the world and our place in it that is more objective than the commonsense view it replaces.

Understanding this bleached-out view of the world draws on our capacities as purely rational thinkers and fails to account for the specific nature of our perceptual sensibility.

Nagel repeatedly returns to the distinction between "primary" and "secondary" qualities—that is, between primary qualities of objects like mass and shape, which are mathematically and structurally describable independent of our sensory apparatuses, and secondary qualities like taste and color, which depend on our sensory apparatuses.

A plausible science of the mind will give an account of the stuff that underpins mental and physical properties in such a way that people will simply be able to see that it necessitates both of these aspects.

Nagel's rationalism and tendency to present human nature as composite, structured around our capacity to reason, explains why he thinks that therapeutic or deflationary accounts of philosophy are complacent and that radical skepticism is, strictly speaking, irrefutable.

[clarification needed] The therapeutic or deflationary philosopher, influenced by Wittgenstein's later philosophy, reconciles people to the dependence of our worldview on our "form of life".

[15] Both ask people to take up an interpretative perspective to making sense of other speakers in the context of a shared, objective world.

"[16] In the 50th-anniversary republication of his article in book form, Nagel writes that he "tried to show that the irreducible subjectivity of consciousness is an obstacle to many proposed solutions to the mind-body problem.

But Kripke argues that one can easily imagine a situation where, for example, one's C-fibres are stimulated but one is not in pain and so refute any such psychophysical identity from the armchair.

This argument that there will always be an explanatory gap between an identification of a state in mental and physical terms is compounded, Nagel argues, by the fact that imagination operates in two distinct ways.

have taken these arguments as helpful for physicalism on the grounds that it exposes a limitation that makes the existence of an explanatory gap seem compelling, while others[who?]

Nagel is not a physicalist because he does not believe that an internal understanding of mental concepts shows them to have the kind of hidden essence that underpins a scientific identity in, say, chemistry.

[18]: 10 Despite Nagel's being an atheist and not a proponent of intelligent design (ID), his book was "praised by creationists", according to the New York Times.

"[19] In 2009, he recommended Signature in the Cell by the philosopher and ID proponent Stephen C. Meyer in The Times Literary Supplement as one of his "Best Books of the Year.

Supervised by John Rawls, he has been a longstanding proponent of a Kantian and rationalist approach to moral philosophy.

But it is important to get the justificatory relations right: when a person accepts a moral judgment they are necessarily motivated to act.

A person who denies the truth of this claim is committed, as in the case of a similar mistake about prudence, to a false view of themself.

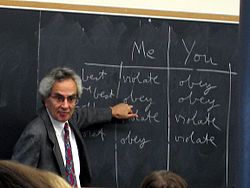

Nagel calls this "dissociation" and considers it a practical analogue of solipsism (the philosophical idea that only one's own mind is sure to exist).

But Nagel remains an individualist who believes in the separateness of persons, so his task is to explain why this objective viewpoint does not swallow up the individual standpoint of each of us.

The result is a hybrid ethical theory of the kind defended by Nagel's Princeton PhD student Samuel Scheffler in The Rejection of Consequentialism.

In addition, in his later work, Nagel finds a rationale for so-called deontic constraints in a way Scheffler could not.

In the Locke lectures published as the book Equality and Partiality, Nagel exposes John Rawls's theory of justice to detailed scrutiny.

Rawls's aim to redress, not remove, the inequalities that arise from class and talent seems to Nagel to lead to a view that does not sufficiently respect the needs of others.

He recommends a gradual move to much more demanding conceptions of equality, motivated by the special nature of political responsibility.

A Rawlsian state permits intolerable inequalities and people need to develop a more ambitious view of equality to do justice to the demands of the objective recognition of the reasons of others.

"[18] In The Last Word, he wrote, "I want atheism to be true and am made uneasy by the fact that some of the most intelligent and well-informed people I know are religious believers.