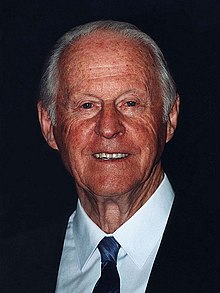

Thor Heyerdahl

Heyerdahl is notable for his Kon-Tiki expedition in 1947, in which he drifted 8,000 km (5,000 mi) across the Pacific Ocean in a primitive hand-built raft from South America to the Tuamotu Islands.

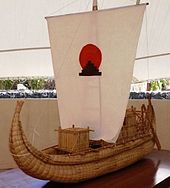

[1][2][3][4] Heyerdahl made other voyages to demonstrate the possibility of contact between widely separated ancient peoples, notably the Ra II expedition of 1970, when he sailed from the west coast of Africa to Barbados in a papyrus reed boat.

[12] It was in this setting, surrounded by the ruins of the formerly glorious Marquesan civilization, that Heyerdahl first developed his theories regarding the possibility of pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact between the pre-European Polynesians, and the peoples and cultures of South America.

[12] The events surrounding his stay on the Marquesas, most of the time on Fatu Hiva, were told first in his book På Jakt etter Paradiset (Hunt for Paradise) (1938), which was published in Norway but, following the outbreak of World War II, was never translated and remained largely forgotten.

Many years later, having achieved notability with other adventures and books on other subjects, Heyerdahl published a new account of this voyage under the title Fatu Hiva (London: Allen & Unwin, 1974).

In 1947 Heyerdahl and five fellow adventurers sailed from Peru to the Tuamotu Islands, French Polynesia in a raft that they had constructed from balsa wood and other native materials, christened the Kon-Tiki.

The Kon-Tiki expedition was inspired by old reports and drawings made by the Spanish Conquistadors of Inca rafts, and by native legends and archaeological evidence suggesting contact between South America and Polynesia.

By 500 CE, a branch of these people were supposedly forced out into Tiahuanaco where they became the ruling class of the Inca Empire and set out to voyage into the Pacific Ocean under the leadership of "Con Ticci Viracocha".

Heyerdahl claimed that these people could count their ancestors who were "white-skinned" right back to the time of Tiki and Hotu Matua, when they first came sailing across the sea "from a mountainous land in the east which was scorched by the sun".

[2] Despite these claims, DNA sequence analysis of Easter Island's current inhabitants indicates that the 36 people living on Rapa Nui who survived the devastating internecine wars, slave raids, and epidemics of the 19th century and had any offspring[27] were Polynesian.

[36][37] Heyerdahl's hypothesis was part of early Eurocentric hyperdiffusionism and the westerner disbelief that (non-white) "stone-age" peoples with "no math" could colonize islands separated by vast distances of ocean water, even against prevailing winds and currents.

Davis says that Heyerdahl "ignored the overwhelming body of linguistic, ethnographic, and ethnobotanical evidence, augmented today by genetic and archaeological data, indicating that he was patently wrong.

The Ra crew included Thor Heyerdahl (Norway), Norman Baker (US), Carlo Mauri (Italy), Yuri Senkevich (USSR), Santiago Genovés (Mexico), Georges Sourial (Egypt), and Abdullah Djibrine (Chad).

The crew discovered that a key element of the Egyptian boatbuilding method had been neglected, a tether that acted like a spring to keep the stern high in the water while allowing for flexibility.

The following year, 1970, a similar vessel, Ra II, was built from Ethiopian papyrus by Bolivian citizens Demetrio, Juan and José Limachi of Lake Titicaca, and likewise set sail across the Atlantic from Morocco, this time with great success.

Apart from the primary aspects of the expedition, Heyerdahl deliberately selected a crew representing a great diversity in race, nationality, religion and political viewpoint in order to demonstrate that, at least on their own little floating island, people could co-operate and live peacefully.

[43] Heyerdahl built yet another reed boat in 1977, Tigris, which was intended to demonstrate that trade and migration could have linked Mesopotamia with the Indus Valley civilization in what is now Pakistan and western India.

In his Open Letter to the UN Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim, Heyerdahl explained his reasons:[45] Today we burn our proud ship ... to protest against inhuman elements in the world of 1978 ... Now we are forced to stop at the entrance to the Red Sea.

Surrounded by military airplanes and warships from the world's most civilised and developed nations, we have been denied permission by friendly governments, for reasons of security, to land anywhere, but in the tiny, and still neutral, Republic of Djibouti.

We must wake up to the insane reality of our time ... We are all irresponsible, unless we demand from the responsible decision makers that modern armaments must no longer be made available to people whose former battle axes and swords our ancestors condemned.

Our planet is bigger than the reed bundles that have carried us across the seas, and yet small enough to run the same risks unless those of us still alive open our eyes and minds to the desperate need of intelligent collaboration to save ourselves and our common civilisation from what we are about to convert into a sinking ship.In the years that followed, Heyerdahl was often outspoken on issues of international peace and the environment.

He spoke of a notation made by Snorri Sturluson, a 13th-century historian-mythographer in Ynglinga Saga, which relates that "Odin (a Scandinavian god who was one of the kings) came to the North with his people from a country called Aser.

Heyerdahl accepted Snorri's story as literal truth, and believed that a chieftain led his people in a migration from the east, westward and northward through Saxony, to Fyn in Denmark, and eventually settling in Sweden.

Heyerdahl claimed that the geographic location of the mythic Aser or Æsir matched the region of contemporary Azerbaijan – "east of the Caucasus mountains and the Black Sea".

[50] He searched for the remains of a civilisation to match the account of Odin in Snorri Sturlusson, significantly further north of his original target of Azerbaijan on the Caspian Sea only two years earlier.

Philologists and historians reject these parallels as mere coincidences, and also anachronisms, for instance the city of Azov did not have that name until over 1,000 years after Heyerdahl claims the Æsir dwelt there.

Heyerdahl hypothesised that the Canarian pyramids formed a temporal and geographic stopping point on voyages between ancient Egypt and the Maya civilization, initiating a controversy in which historians, esoterics, archaeologists, astronomers, and those with a general interest in history took part.

Heyerdahl believed that these finds fit with his theory of a seafaring civilisation which originated in what is now Sri Lanka, colonised the Maldives, and influenced or founded the cultures of ancient South America and Easter Island.

The voyage, organised by Torgeir Higraff and called the Tangaroa Expedition,[64] was intended as a tribute to Heyerdahl, an effort to better understand navigation via centreboards ("guara[65]") as well as a means to monitor the Pacific Ocean's environment.

The book has numerous photos from the Kon-Tiki voyage 60 years earlier and is illustrated with photographs by Tangaroa crew member Anders Berg (Oslo: Bazar Forlag, 2007).