Three-age system

The system appealed to British researchers working in the academic field of ethnology – they adopted it to establish race sequences for Britain's past based on cranial types.

[8] The schema, however, has little or no utility for establishing chronological frameworks in sub-Saharan Africa, much of Asia, the Americas, and some other areas; and has little importance in contemporary archaeological or anthropological discussion for these regions.

The concept of dividing pre-historical ages into systems based on metals extends far back in European history, probably originated by Lucretius in the first century BC.

In his poem Works and Days, the ancient Greek poet Hesiod, possibly between 750 and 650 BC, defined five successive Ages of Man: Golden, Silver, Bronze, Heroic and Iron.

The different phases of their collective life are marked by the accumulation of customs to form material civilization:[17] The earliest weapons were hands, nails and teeth.

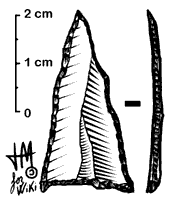

By the 16th century, a tradition had developed based on observational incidents, true or false, that the black objects found widely scattered in large quantities over Europe had fallen from the sky during thunderstorms and were therefore to be considered generated by lightning.

[20] His view was based on what may be the first in-depth lithic analysis of the objects in his collection, which led him to believe that they are artifacts and to suggest that the historical evolution of these artefacts followed a scheme.

On 12 November 1734, Nicholas Mahudel, physician, antiquarian and numismatist, read a paper at a public sitting of the Académie Royale des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres in which he defined three "usages" of stone, bronze and iron in a chronological sequence.

After cautioning the audience that natural and man-made objects are often easily confused, he asserts that the specific "figures" or "formes that can be distinguished (formes qui les font distingues)" of the stones were man-made, not natural:[25] It was Man's hand that made them serve as instruments (C'est la main des hommes qui les leur a données pour servir d'instrumens...)Their cause, he asserts, is "the industry of our forefathers (l'industrie de nos premiers pères)."

His use of l'industrie foreshadows the 20th century "industries", but where the moderns mean specific tool traditions, Mahudel meant only the art of working stone and metal in general.

In 1821 he wrote in a letter to fellow prehistorian Schröder:[33] nothing is more important than to point out that hitherto we have not paid enough attention to what was found together.and in 1822: we still do not know enough about most of the antiquities either; ... only future archaeologists may be able to decide, but they will never be able to do so if they do not observe what things are found together and our collections are not brought to a greater degree of perfection.This analysis emphasizing co-occurrence and systematic attention to archaeological context allowed Thomsen to build a chronological framework of the materials in the collection and to classify new finds in relation to the established chronology, even without much knowledge of their provenience.

[37] He already had an international reputation when in 1836 the Royal Society of Northern Antiquaries published his illustrated contribution to "Guide to Scandinavian Archaeology" in which he put forth his chronology together with comments about typology and stratigraphy.

His published and personal advice to Danish archaeologists concerning the best methods of excavation produced immediate results that not only verified his system empirically but placed Denmark in the forefront of European archaeology for at least a generation.

Just as the paleontologist uses modern elephants to help reconstruct fossil pachyderms, so the archaeologist is justified in using the customs of the "non-metallic savages" of today to understand "the early races which inhabited our continent.

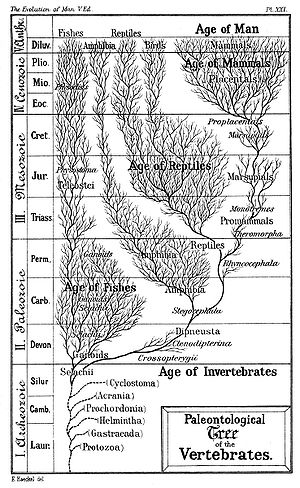

In 1867–68 Ernst Haeckel in 20 public lectures in Jena, entitled General Morphology, to be published in 1870, referred to the Archaeolithic, the Palaeolithic, the Mesolithic and the Caenolithic as periods in geologic history.

In that same year, 1872, Sir John Evans produced a massive work, The Ancient Stone Implements, in which he in effect repudiated the Mesolithic, making a point to ignore it, denying it by name in later editions.

However, asserted Piette:[56] I was fortunate to discover the remains of that unknown time which separated the Magdalenian age from that of polished stone axes ... it was, at Mas-d'Azil in 1887 and 1888 when I made this discovery.He had excavated the type site of the Azilian Culture, the basis of today's Mesolithic.

In reality, the final phase of the Capsian, the Tardenoisian, the Azilian and the northern Maglemose industries are the posthumous descendants of the Palaeolithic ...The ideas of Stjerna and Obermaier introduced a certain ambiguity into the terminology, which subsequent archaeologists found and find confusing.

His History of Creation of 1870 presents the ages as "Strata of the Earth's Crust", in which he prefers "upper", "mid-" and "lower" based on the order in which one encounters the layers.

In the 1833 edition of Principles of Geology (the first) Lyell devised the terms Eocene, Miocene and Pliocene to mean periods of which the "strata" contained some (Eo-, "early"), lesser (Mio-) and greater (Plio-) numbers of "living Mollusca represented among fossil assemblages of western Europe.

Worsaae in 1862 in Om Tvedelingen af Steenalderen, previewed in English even before its publication by The Gentleman's Magazine, concerned about changes in typology during each period, proposed a bipartite division of each age:[72]Both for Bronze and Stone it was now evident that a few hundred years would not suffice.

And so it is not surprising that in the 1874 Stockholm meeting of the International Congress of Prehistoric Anthropology and Archaeology, in response to Ernst Hamy's denial of any "break" between Paleolithic and Neolithic based on material from dolmens near Paris "showing a continuity between the paleolithic and neolithic folks," Edouard Desor, geologist and archaeologist, replied:[75] "that the introduction of domesticated animals was a complete revolution and enables us to separate the two epochs completely."

For that is the period when primitive agriculture developed and cattle breeding began.In 1936 a champion came forward who would advance the Neolithic Revolution into the mainstream view: Vere Gordon Childe.

Lubbock created such concepts as savages and barbarians based on the customs of then modern tribesmen and made the presumption that the terms can be applied without serious inaccuracy to the men of the Paleolithic and the Neolithic.

According to his 1886 biographers, Luigi Pigorini and Pellegrino Strobel, Chierici devised the term Età Eneo-litica to describe the archaeological context of his findings, which he believed were the remains of Pelasgians, or people that preceded Greek and Latin speakers in the Mediterranean.

Sir John's own son, Arthur Evans, beginning to come into his own as an archaeologist and already studying Cretan civilization, refers in 1895 to some clay figures of "aeneolithic date" (quotes his).

By convention among archaeologists: The question of the dates of the objects and events discovered through archaeology is the prime concern of any system of thought that seeks to summarize history through the formulation of ages or epochs.

In the case where parallel epochs defined in history were available, elaborate efforts were made to align European and Near Eastern sequences with the datable chronology of Ancient Egypt and other known civilizations.

Vere Gordon Childe said of the early cultural anthropologists:[93]Last century Herbert Spencer, Lewis H. Morgan and Tylor propounded divergent schemes ... they arranged these in a logical order ....

Connah argues:[94]As radiocarbon and other forms of absolute dating contributed more detailed and more reliable chronologies, the epochal model ceased to be necessary.Peter Bogucki of Princeton University summarizes the perspective taken by many modern archaeologists:[96] Although modern archaeologists realize that this tripartite division of prehistoric society is far too simple to reflect the complexity of change and continuity, terms like 'Bronze Age' are still used as a very general way of focusing attention on particular times and places and thus facilitating archaeological discussion.Another common criticism attacks the broader application of the three-age system as a cross-cultural model for social change.

Nahal Hever Canyon , Israel Museum , Jerusalem