Thor

In Norse mythology, he is a hammer-wielding god associated with lightning, thunder, storms, sacred groves and trees, strength, the protection of humankind, hallowing, and fertility.

Besides Old Norse Þórr, the deity occurs in Old English as Thunor, in Old Frisian as Thuner, in Old Saxon as Thunar, and in Old High German as Donar, all ultimately stemming from the Proto-Germanic theonym *Þun(a)raz, meaning 'Thunder'.

Thor is a prominently mentioned god throughout the recorded history of the Germanic peoples, from the Roman occupation of regions of Germania, to the Germanic expansions of the Migration Period, to his high popularity during the Viking Age, when, in the face of the process of the Christianization of Scandinavia, emblems of his hammer, Mjölnir, were worn and Norse pagan personal names containing the name of the god bear witness to his popularity.

In stories recorded in medieval Iceland, Thor bears at least fifteen names, is the husband of the golden-haired goddess Sif and the lover of the jötunn Járnsaxa.

Thor has two servants, Þjálfi and Röskva, rides in a cart or chariot pulled by two goats, Tanngrisnir and Tanngnjóstr (whom he eats and resurrects), and is ascribed three dwellings (Bilskirnir, Þrúðheimr, and Þrúðvangr).

Thor's exploits, including his relentless slaughter of his foes and fierce battles with the monstrous serpent Jörmungandr—and their foretold mutual deaths during the events of Ragnarök—are recorded throughout sources for Norse mythology.

[7] These Proto-Germanic forms are probably further related to the common Proto-Indo-European root for 'thunder' *(s)tenh₂-, also attested in the Latin epithet Tonans (attached to Jupiter) and the Vedic stanáyati ("thunders").

[8] Scholar Peter Jackson argues that those theonyms may have emerged as the result of the fossilization of an original epithet (or epiclesis, i.e. invocational name) of the Proto-Indo-European thunder-god *Perkwunos, since the Vedic weather-god Parjanya is also called stanayitnú- ('Thunderer').

All of these terms derive from a Late Proto-Germanic weekday name along the lines of *Þunaresdagaz ('Day of *Þun(a)raz'), a calque of Latin Iovis dies ('Day of Jove'; cf.

The first clear example of this occurs in the Roman historian Tacitus's late first-century work Germania, where, writing about the religion of the Suebi (a confederation of Germanic peoples), he comments that "among the gods Mercury is the one they principally worship.

[15] In his Annals, Tacitus again refers to the veneration of "Hercules" by the Germanic peoples; he records a wood beyond the river Weser (in what is now northwestern Germany) as dedicated to him.

[17] The first recorded instance of the name of the god appears upon the Nordendorf fibulae, a piece of jewelry created during the Migration Period and found in Bavaria.

[22] The Kentish royal legend, probably 11th-century, contains the story of a villainous reeve of Ecgberht of Kent called Thunor, who is swallowed up by the earth at a place from then on known as þunores hlæwe (Old English 'Thunor's mound').

[32] In the Poetic Edda, compiled during the 13th century from traditional source material reaching into the pagan period, Thor appears (or is mentioned) in the poems Völuspá, Grímnismál, Skírnismál, Hárbarðsljóð, Hymiskviða, Lokasenna, Þrymskviða, Alvíssmál, and Hyndluljóð.

[33] In the poem Völuspá, a dead völva recounts the history of the universe and foretells the future to the disguised god Odin, including the death of Thor.

In anger smites the warder of earth,— Forth from their homes must all men flee;— Nine paces fares the son of Fjorgyn, And, slain by the serpent, fearless he sinks.

[38] Thor is the main character of Hárbarðsljóð, where, after traveling "from the east", he comes to an inlet where he encounters a ferryman who gives his name as Hárbarðr (Odin, again in disguise), and attempts to hail a ride from him.

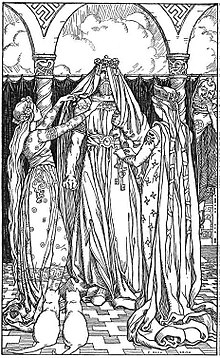

At the thing, the god Heimdallr puts forth the suggestion that, in place of Freyja, Thor should be dressed as the bride, complete with jewels, women's clothing down to his knees, a bridal head-dress, and the necklace Brísingamen.

[51] In the poem Alvíssmál, Thor tricks a dwarf, Alvíss, to his doom upon finding that he seeks to wed his daughter (unnamed, possibly Þrúðr).

In a long question and answer session, Alvíss does exactly that; he describes natural features as they are known in the languages of various races of beings in the world, and gives an amount of cosmological lore.

In Ynglinga saga chapter 5, a heavily euhemerized account of the gods is provided, where Thor is described as having been a gothi—a pagan priest—who was given by Odin (who himself is explained away as having been an exceedingly powerful magic-wielding chieftain from the east) a dwelling in the mythical location of Þrúðvangr, in what is now Sweden.

[64] In the Netherlands, The Sagas of Veluwe has a story called Ontstaan van het Uddeler- en Bleeke meer which features Thor and his fight with the Winter Giants.

The Eyrarland Statue, a copper alloy figure found near Akureyri, Iceland dating from around the 11th century, may depict Thor seated and gripping his hammer.

Cultic significance may only be assured in place names containing the elements -vé (signifying the location of a vé, a type of pagan Germanic shrine), –hóf (a structure used for religious purposes, see heathen hofs), and –lundr (a holy grove).

The place name Þórslundr is recorded with particular frequency in Denmark (and has direct cognates in Norse settlements in Ireland, such as Coill Tomair), whereas Þórshof appears particularly often in southern Norway.

[73] Thor closely resembles other Indo-European deities associated with the thunder: the Celtic Taranis,[74][75] the Estonian Taara (or Tharapita), the Baltic Perkūnas, the Slavic Perun,[76] and particularly the Hindu Indra, whose thunderbolt weapon the vajra is an obvious parallels noted already by Max Müller.

[75] Although in the past it was suggested that Thor was an indigenous sky god or a Viking Age import into Scandinavia, these Indo-European parallels make him generally accepted today as ultimately derived from a Proto-Indo-European deity.

In our own times, little stone axes from the distant past have been used as fertility symbols and placed by the farmer in the holes made by the drill to receive the first seed of spring.

[85] In English he features for example in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's "The Challenge of Thor" (1863)[86] and in two works by Rudyard Kipling: Letters of Travel: 1892–1913 and "Cold Iron" in Rewards and Fairies.

In the show, a high school student, Magne Seier, receives Thor's powers and abilities to fight the giants that are polluting Norway and murdering people.